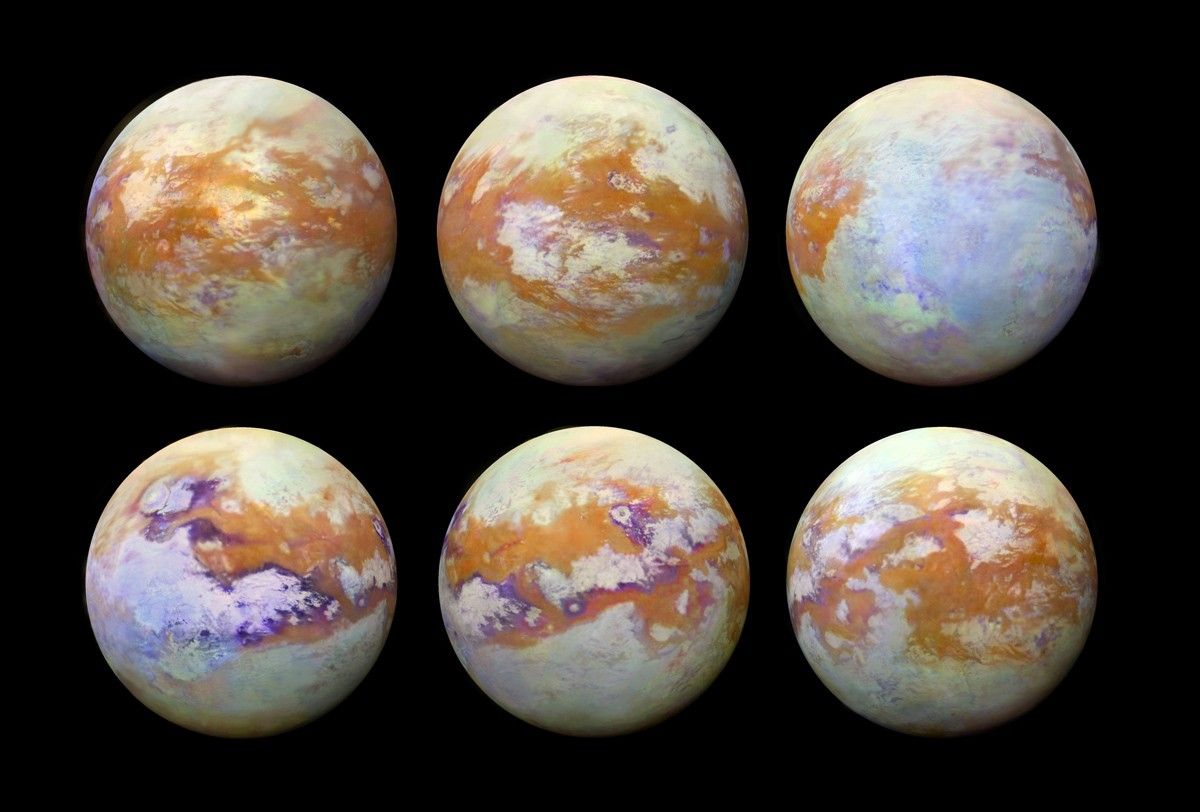

For more than a decade, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft traced Saturn’s rings and moons, returning some of the most detailed planetary data ever collected. Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, drew special focus. Across 124 close flybys, Cassini revealed a hazy atmosphere, methane lakes, and a surprisingly complex interior. Ten of those flybys targeted Titan’s gravity field, offering early clues about how mass is arranged beneath its icy surface.

Those early gravity measurements suggested a thick hydrosphere, roughly 600 kilometers deep, and a low-density rocky core. They also fueled a long-standing idea that Titan hides a global ocean of liquid water beneath its ice shell. That possibility mattered because liquid water, even far from the Sun, is central to many ideas about habitability beyond Earth.

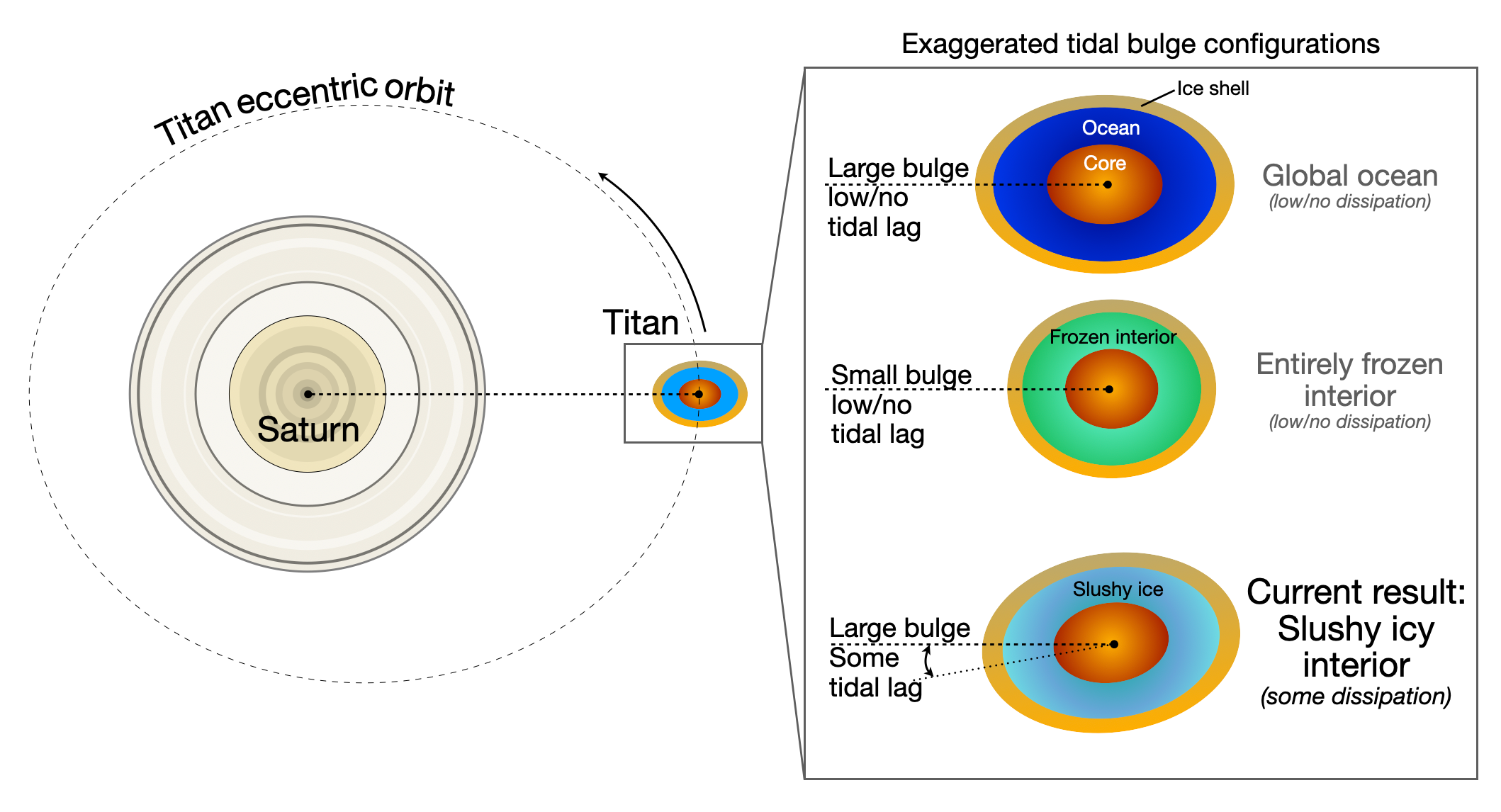

A new analysis of Cassini data now challenges that view. By reexamining how Titan’s gravity responds to Saturn’s pull, researchers found signs of intense internal friction and heat generation. The results point away from a vast hidden ocean. Instead, they suggest Titan’s deep interior may be dominated by a thick, slushy layer of high-pressure ice.

As Titan moves along its slightly stretched orbit, Saturn’s gravity squeezes and releases the moon. This tidal forcing subtly reshapes Titan and changes its gravity field. Cassini tracked these shifts by sending radio signals back to Earth during each flyby. Tiny changes in the signal revealed how Titan responded to Saturn’s tug.

In the new study, scientists reprocessed Cassini’s radio tracking data using improved techniques. These methods reduced noise in the signal by about 25 to 30 percent. With cleaner data, the team measured Titan’s gravity and tidal response more precisely than before.

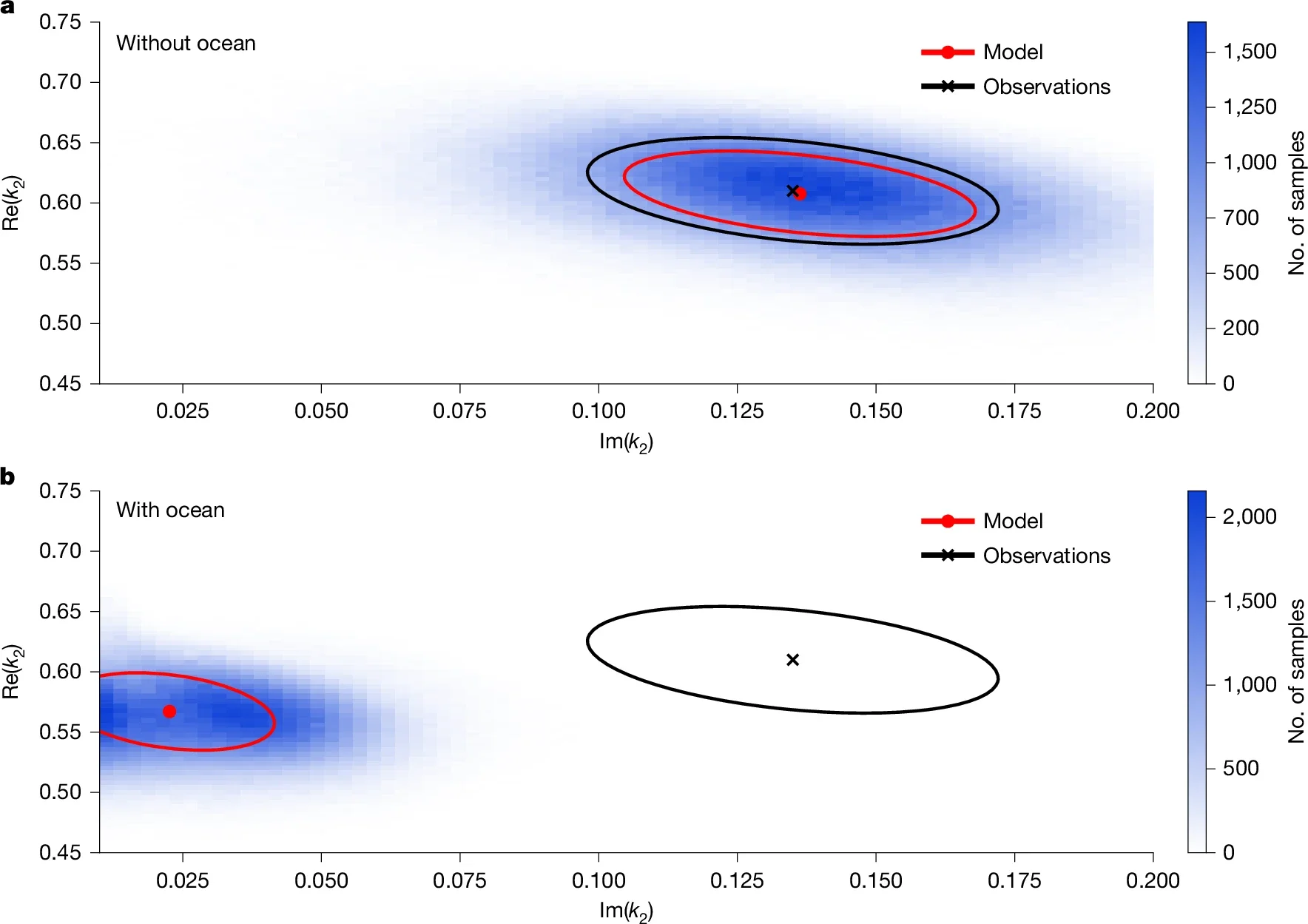

One key number is the tidal Love number, known as k2. Its real part, Re(k2), describes how much Titan deforms under Saturn’s gravity. The new value, 0.608 plus or minus 0.048, matches earlier results showing Titan responds strongly to tides.

The surprise came from the imaginary part, Im(k2), which had never been measured directly. This term captures how much Titan’s response lags behind the applied force. That lag only occurs when internal friction turns tidal energy into heat. The team measured Im(k2) at 0.135 plus or minus 0.035. That is far larger than expected.

This value corresponds to a tidal quality factor of about 4.5. Earth’s value is near 300. Mars sits around 90. Titan, by comparison, dissipates tidal energy very efficiently.

A large Im(k2) means Titan’s interior resists deformation and loses energy as heat. That behavior clashes with models that include a global subsurface ocean. Liquid water would allow the ice shell to flex more easily, reducing internal friction.

To test this, the researchers built detailed interior models, some with an ocean and some without. They used a Bayesian approach and a Markov chain Monte Carlo algorithm to explore a wide range of possible interiors. Each model had to match Titan’s mass, gravity field, moment of inertia, and tidal response.

In ocean-bearing models, the maximum Im(k2) reached only about 0.050. That falls far short of the measured value. The mismatch ruled out a global ocean beneath Titan’s ice shell.

In contrast, ocean-free models reproduced both Re(k2) and Im(k2) at the same time. In these scenarios, most tidal energy is lost within a thick layer of high-pressure ice above the rocky core. This ice can deform slowly over Titan’s 15.9-day tidal cycle if its viscosity is near 10^12 pascal-seconds. Laboratory experiments show this value is plausible for ice phases V and VI near their melting points.

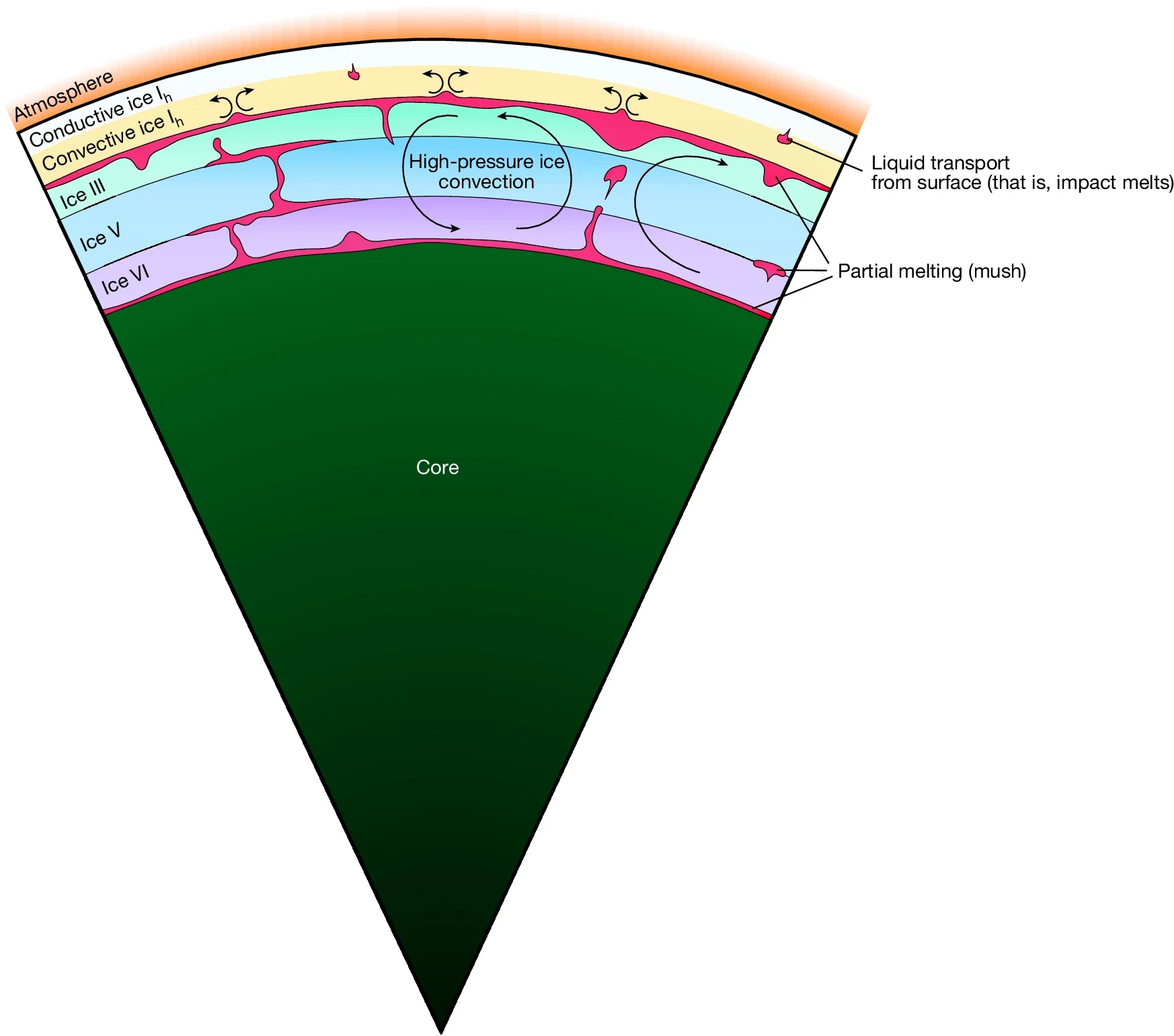

The emerging picture replaces a hidden sea with something stranger. Beneath Titan’s cold surface lies a thick shell of ordinary ice, known as ice Ih. Below that sits a massive layer of high-pressure ice that behaves more like slush than solid rock.

“This deep ice layer may be hundreds of kilometers thick. It deforms under tidal stress, generating about 4 terawatts of heat. That is roughly ten times more heat than radioactive decay alone could supply. About 3.5 terawatts come from the high-pressure ice itself,” Baptiste Journaux, a University of Washington assistant professor of Earth and space sciences, explained to The Brighter Side of News.

“The rocky core beneath appears unusually light. Its density points to a large fraction of hydrated minerals or organic-rich material rather than dry rock. That composition affects how heat flows and how the ice above behaves,” he continued.

Recent laboratory work also supports the absence of a global ocean. Scientists have identified a thermodynamic limit below which liquid water cannot exist, regardless of pressure or salt content. For Titan, this limit caps the thickness of the outer ice shell at about 167 kilometers. The new interior model stays within that bound.

Titan’s methane-rich atmosphere remains another puzzle. Methane breaks down under sunlight and must be replenished over time. The study suggests that methane clathrates, icy cages that trap gas molecules, could play a role.

A clathrate layer just a few kilometers thick could slowly release methane for billions of years. At the same time, it would help trap heat inside, supporting the warm, deformable ice layer below.

Titan’s strong tidal dissipation also reshapes ideas about the Saturn system. If Titan loses energy this quickly, its orbital eccentricity should decay in about 30 million years. That implies its current orbit is relatively young.

This finding hints at a dynamic past. Titan’s orbit may have been altered by interactions with Saturn, collisions, or even the loss of another moon. Models that explain Titan’s outward migration must now account for Titan itself dissipating large amounts of energy.

For years, Titan stood as a prime candidate for a hidden ocean world. Its shape, tilt, and tidal response seemed to point in that direction. Yet no single model could explain all observations at once.

The new analysis brings those pieces together without invoking an ocean. It shows that strong tides do not guarantee liquid water. In some cases, intense pressure and heat produce thick, convecting ice instead.

That insight matters beyond Saturn. Many icy moons are assumed to host global oceans. Titan’s case suggests some may instead contain slushy layers with small pockets of melt. Even a tiny melt fraction could still matter. At just 1 percent melt, Titan’s hydrosphere would contain a volume of liquid equal to Earth’s Atlantic Ocean.

Such environments might resemble Earth’s polar sea ice, where life survives in cold, salty microenvironments. “Instead of an open ocean like we have here on Earth, we’re probably looking at something more like Arctic sea ice or aquifers, which has implications for what type of life we might find, but also the availability of nutrients, energy and so on,” Journaux explained.

Earlier Cassini studies focused on how much Titan deformed. The new work added a crucial detail: when that deformation occurred. Titan’s shape changes lag about 15 hours behind Saturn’s strongest pull.

That delay revealed how much energy is needed to stir Titan’s interior. “Nobody was expecting very strong energy dissipation inside Titan. That was the smoking gun indicating that Titan’s interior is different from what was inferred from previous analyses,” said Flavio Petricca, a postdoctoral fellow at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory who led the study.

Petricca measured subtle shifts in Cassini’s radio signals. Journaux helped interpret the results using data from high-pressure experiments at his planetary cryo-mineral physics laboratory. “The watery layer on Titan is so thick, the pressure is so immense, that the physics of water changes. Water and ice behave in a different way than sea water here on Earth,” Journaux said.

The study was published in Nature and included collaboration from Ula Jones, a University of Washington graduate student. Jones noted, “The discovery of a slushy layer on Titan also has exciting implications for the search for life beyond our solar system. It expands the range of environments we might consider habitable.”

The findings arrive as NASA prepares its next mission to Titan. Dragonfly, a nuclear-powered rotorcraft, is scheduled for launch in 2028. It will explore Titan’s surface and sample its chemistry.

Journaux is part of the Dragonfly team. The new interior model will help guide what the mission looks for, from seismic signals to surface features shaped by deep processes. While a global ocean now seems unlikely, Titan remains one of the most intriguing worlds in the solar system.

Careful reanalysis of decades-old data shows that Titan is not simpler than expected. It is more complex. Beneath its icy crust lies a vast, slowly moving mixture of ice and melt that forces scientists to rethink where liquid water exists and how life might arise far from the Sun.

These findings reshape how scientists assess habitability on icy worlds. They show that strong tides do not always create global oceans. Instead, slushy ice layers may dominate, changing where liquid water and nutrients collect.

For future missions, the work refines where to search for signs of life. Small melt pockets within ice could concentrate chemicals and energy more effectively than a deep ocean. The results also influence models of moon formation and orbital evolution across the solar system and beyond.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Titan’s interior is slushy ice, not a hidden ocean, Cassini data finds appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.