Car dashboards once relied on buttons and knobs you could adjust by feel. Today, large touchscreens dominate vehicle interiors, making navigation and media easier to access but harder to use without looking away from the road. New research from the University of Washington and the Toyota Research Institute examines how this shift affects drivers when attention is already stretched thin.

The study was led by researchers at the University of Washington, including James Fogarty of the Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science and Engineering and Jacob O. Wobbrock of the Information School, working with Toyota Research Institute.

“We all know it’s dangerous to use your phone while driving,” Fogarty said. “But what about the car’s touch screen? We wanted to understand that interaction so we can design interfaces specifically for drivers.”

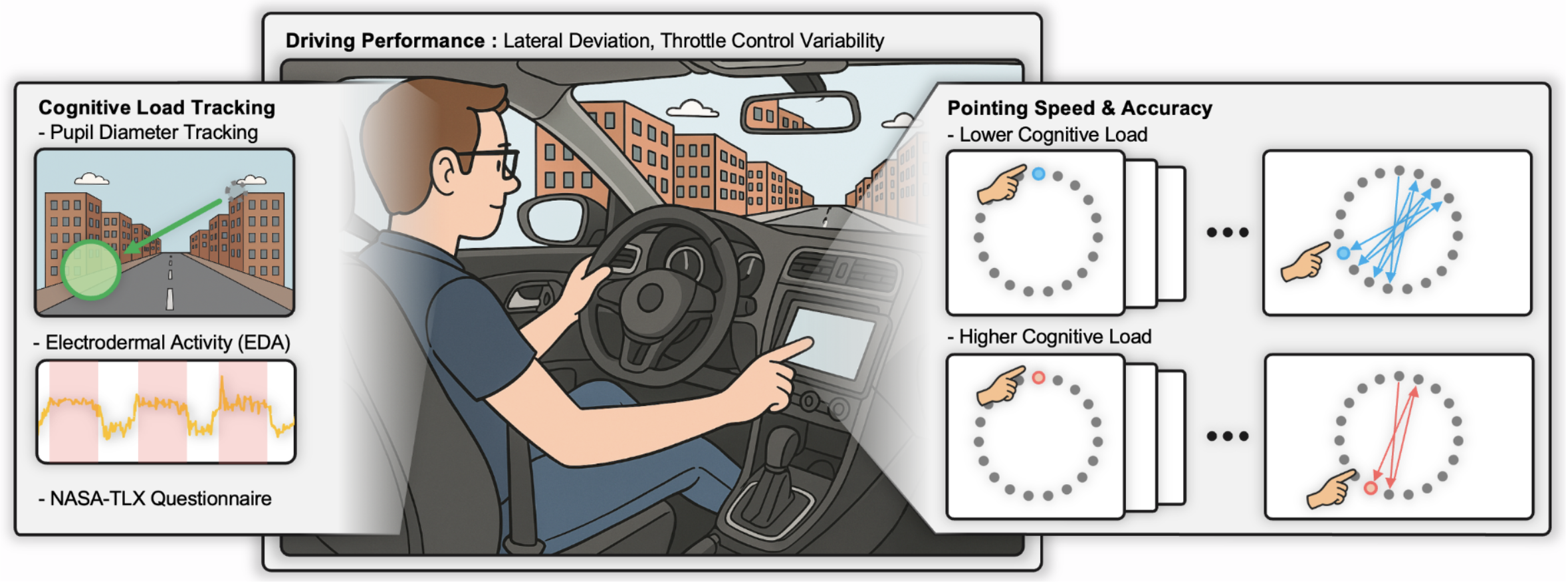

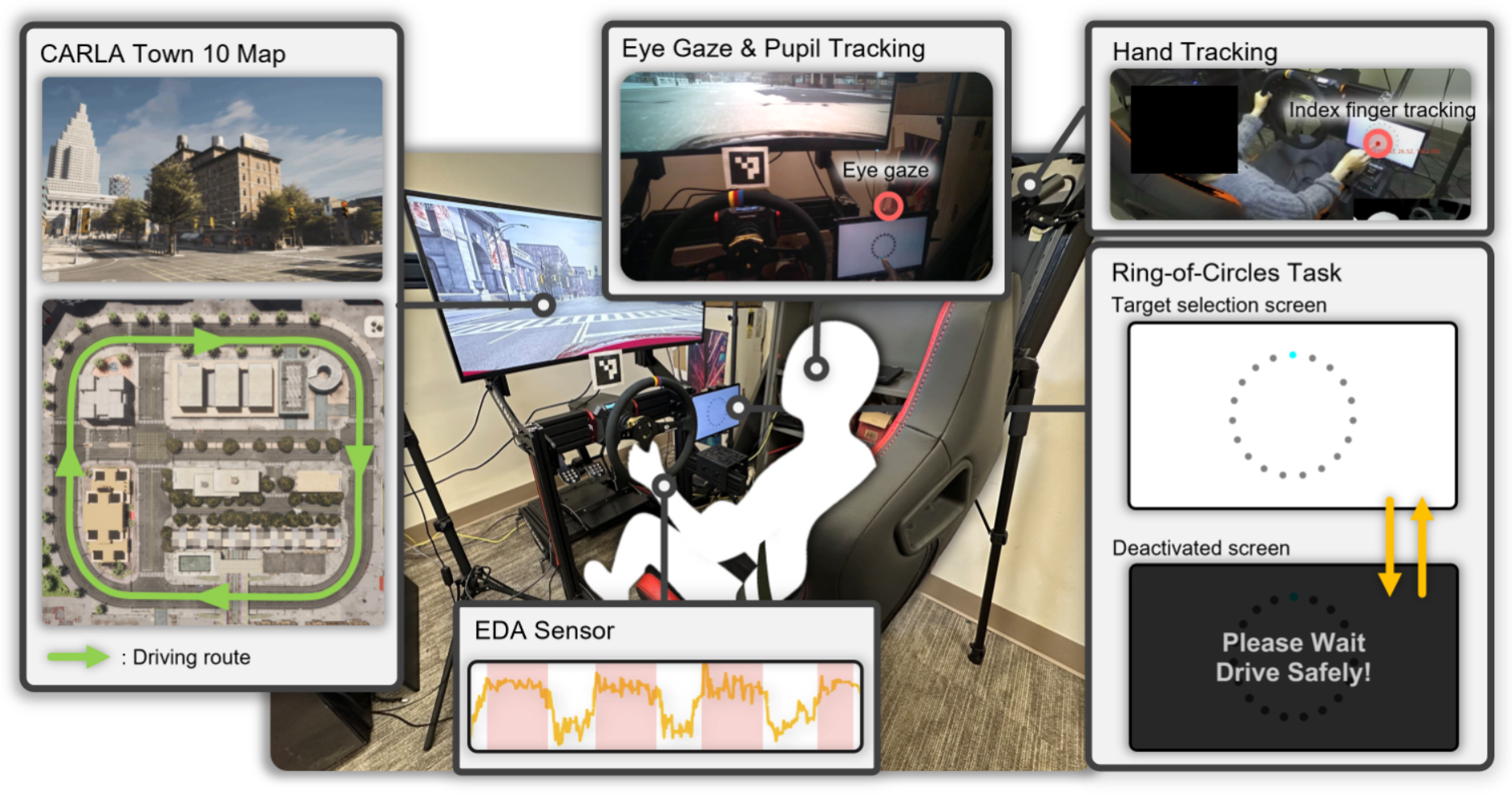

To answer that question, the team built a demanding test environment. You drove through a realistic simulator while using a dashboard-style touchscreen and completing memory tasks meant to reflect mental strain from traffic or complex driving situations. The goal was not just to see whether driving or touchscreen use suffered, but how each task affected the other when they competed for the same attention.

Sixteen adults took part in the experiment. They averaged about 26 years old and had nearly six years of driving experience. Before the tests began, each participant adjusted the simulator to fit their comfort and practiced the tasks.

While driving, you tapped targets on a 12-inch touchscreen, similar to selecting apps or controls in a modern car. At the same time, you completed a memory challenge known as an N-back task. In this exercise, you heard a stream of numbers and had to repeat one heard moments earlier. The task increased in difficulty as it required remembering numbers further back in the sequence.

Sensors tracked your eye movements, hand motion, pupil size, and skin response. Pupil growth and skin conductivity are widely used measures of mental effort. You also rated how demanding each condition felt using a standard workload survey.

As memory demands increased, every measure confirmed that mental load rose. Participants reported feeling more rushed and less successful. Their pupils widened, and physiological signs of effort became stronger. The setup succeeded in pushing attention to its limits.

When touchscreen interaction entered the picture, driving quality declined. Vehicles drifted within the lane about 42% more often when drivers used the screen. Steering became less stable, even though participants had been told to prioritize safe driving.

Adding the memory task did not further worsen steering or throttle control. That result suggests drivers compensated by shifting effort away from the touchscreen. They protected lane keeping by slowing down or simplifying how they used the display.

Safety agencies often warn that glances away from the road should last no more than two seconds. The study showed drivers tried to respect that limit when mental demand climbed, but the cost appeared elsewhere.

Touchscreen performance dropped sharply once driving began. Speed and accuracy together fell by nearly 60% when participants drove while tapping targets. When memory load increased further, touchscreen efficiency declined again.

Drivers did not become wildly inaccurate. Instead, they slowed down to stay precise. Movement times grew longer, and overall efficiency fell. This tradeoff showed that attention was limited. When driving and thinking harder, you preserved accuracy by sacrificing speed.

Making touchscreen buttons larger did not solve the problem. The researchers found that size alone failed to improve performance under load.

“If people struggle with accuracy on a screen, usually you want to make bigger buttons,” said Xiyuan Alan Shen, a doctoral student in the Allen School. “But in this case, since people move their hand to the screen before touching, the thing that takes time is the visual search.”

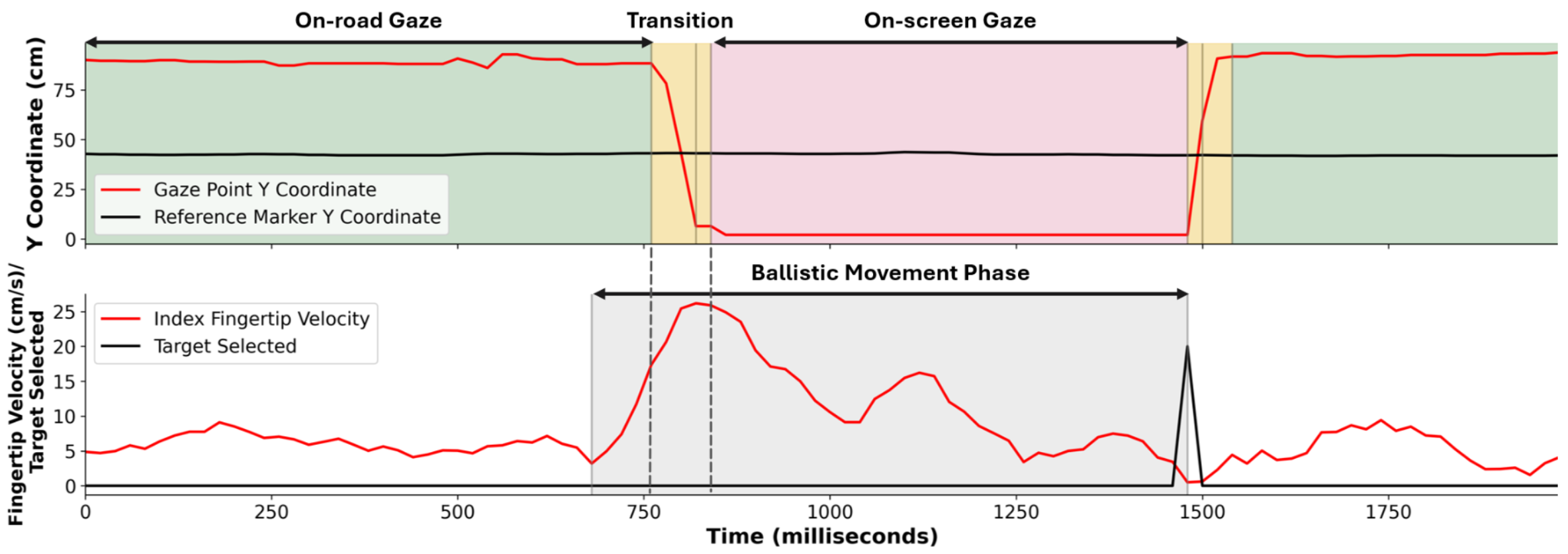

Eye-tracking revealed a striking pattern. In most tasks, eyes move first and guide the hand. Here, the opposite often happened. Drivers frequently reached toward the screen before looking at it.

“Our team found that “hand-before-eye” behavior appeared in nearly two-thirds of interactions with no added memory task. Under higher mental load, it rose above 70%. Drivers seemed to rely on memory to start the movement, then paused mid-action while waiting for visual confirmation,” Fogarty shared with The Brighter Side of News.

“Glances at the touchscreen also grew shorter as mental load increased. Average off-road looks dropped by more than a quarter. Long glances over two seconds became far less common. These shorter looks did not signal safer interaction. Instead, they reflected a reduced ability to handle extended visual attention away from the road,” he continued.

The findings show that driving, touchscreen use, and mental strain draw from the same pool of attention. When that pool runs low, drivers protect basic vehicle control by cutting back on screen interaction.

“Touch screens are widespread today in automobile dashboards, so it is vital to understand how interacting with touch screens affects drivers and driving,” Wobbrock said. “Our research is some of the first that scientifically examines this issue, suggesting ways for making these interfaces safer and more effective.”

The researchers suggest future systems could adapt in real time. Simple sensors, such as eye tracking or touch sensors on the steering wheel, could estimate mental load. Interfaces might then highlight essential controls, reduce steps, or delay noncritical tasks during demanding moments.

This work offers guidance for carmakers and interface designers as touchscreens become standard. By showing that drivers slow and ration attention under load, the study points to safer design choices that match human limits. Adaptive interfaces could reduce distraction without removing useful features.

Over time, these insights may lead to dashboards that respond to driver stress, lowering crash risk and improving trust in vehicle technology.

Research findings are available online in the journal ACM Association for Computing Machinery.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Touchscreens, attention, and the dangers of multitasking while driving appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.