In trying to come to grips with a surprisingly big and wide-ranging electoral victory by Donald Trump and his Republican Party on November 5, the search for precedents is inevitable. And to a lot of shell-shocked Democrats with a grasp of political history, comparisons to the election of 1980 make some sense. Then as now, close polls failed to accurately predict a big late lurch of support toward the GOP candidate. Then as now, an incumbent Democrat with a reputation for economic and foreign-policy fecklessness was a sitting duck for a simple campaign promising change. Then as now, runaway inflation and correspondingly high interest rates ravaged working-class fidelity to the party of FDR. And then as now, that party had developed an unsavory reputation for subservience to interest groups and out-of-the-mainstream elitism.

Ronald Reagan was no Donald Trump; you have to go all the way back to presidents like Andrew Johnson to find anyone whose brand of “populism” was so crude and racially loaded. The Gipper was famously sunny. But it’s difficult to convey to anyone who wasn’t an adult in 1980 how terrifying he seemed to liberals: a “grade-B movie actor” who led and symbolized the takeover of his own party by extremist ideologues, a coalition of unreconstructed southern segregationists, Nixonian cold warriors, laissez-faire anti-government cranks, and newly politicized conservative Evangelicals.

Meanwhile, decades of conservative mockery of Reagan’s victim, Jimmy Carter, have definitely obscured the fact that the 1980 election felt, and according to the polls truly was, competitive until the very end. The average polling error was 6 percent, meaning the polls overestimated Carter’s vote by that significant of an extent. Reagan won by 9.7 percent, carrying 44 states and earning 489 electoral votes, and Republicans flipped control of the Senate for the first time since 1954.

The shock of the 1980 results was actually greater than what we’ve seen among Democrats and nonpartisan observers this year. While there was plenty of contempt for the defeated incumbent among those watching in horror as Reagan (with a policy and personnel blueprint from the Heritage Foundation) prepared to take office, the circumstances were very different from those of 2024 (aside from the fact that the current incumbent stepped aside and let his vice-president wage a much better campaign). Far from being pushed out of a reelection bid by anxious Democrats thinking he was un-reelectable, Jimmy Carter defeated a primary challenge from Ted Kennedy in something of an upset. And Reagan’s prospects were initially damaged by the independent candidacy of one of his defeated primary rivals, John Anderson (who in the end veered left and probably took more votes away from Carter than Reagan).

Different as it was in how it developed and unfolded, the scary thing about the 1980 precedent for Democrats is that Reagan’s singular win over a damaged incumbent turned out to represent a genuine policy revolution. The new administration unearthed an obscure device called “budget reconciliation” that enabled it in early 1981 to package a vast array of legislation into one huge bill that passed on up-or-down votes (it immediately repeated the trick with tax-cut proposals). Assuming Republicans, as expected, hang onto control of the House, this same device will be available to Team Trump in 2025 to enact whatever policy changes he can’t impose via his expanded willingness to rule by executive order.

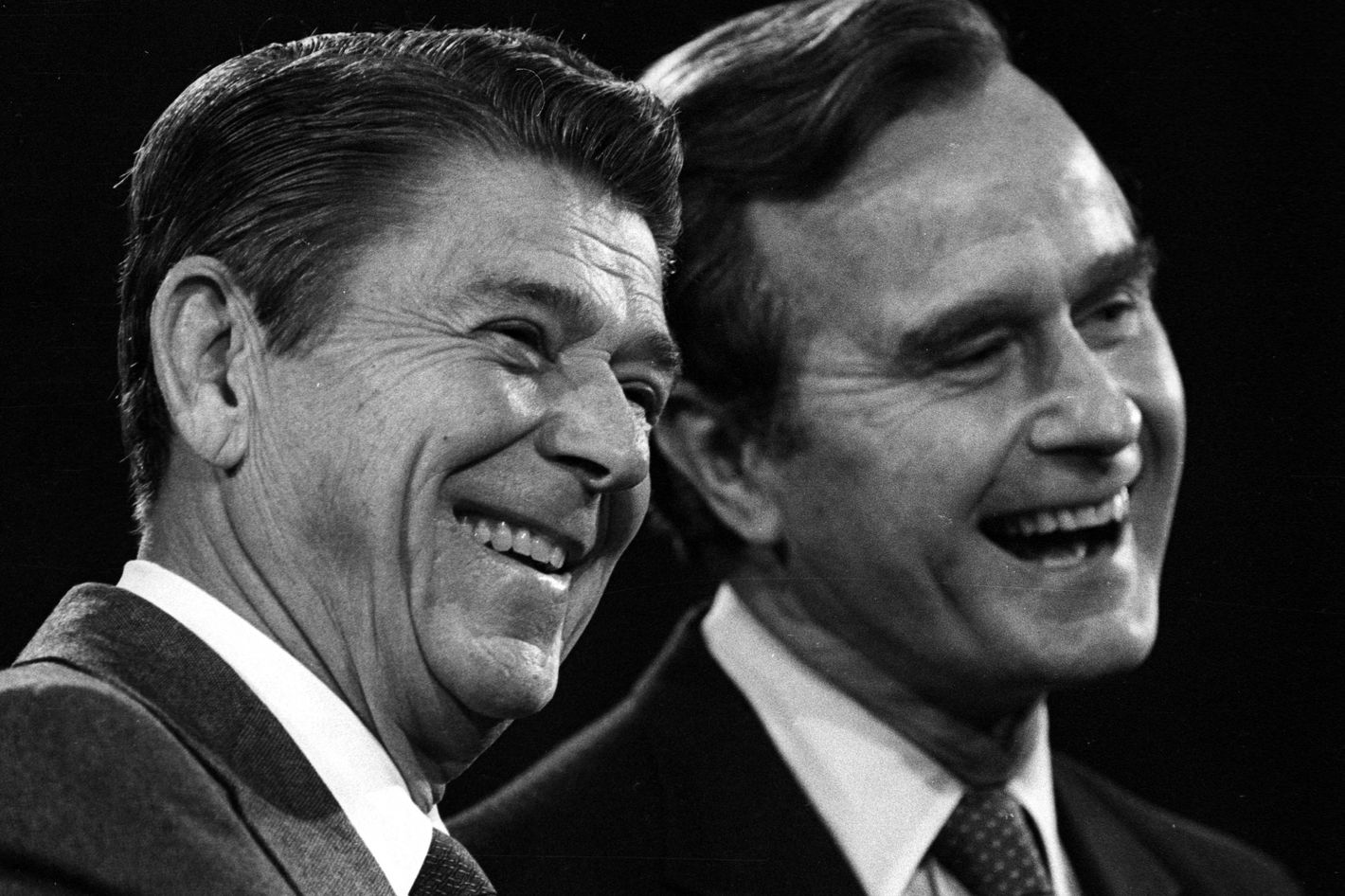

The Reagan Revolution wasn’t, however, just a big change in federal policymaking: It already represented a political realignment that gave Republicans (at least in presidential elections) an enduring majority to support its newly radical agenda. Millions of so-called “Reagan Democrats” (particularly conservative white southerners and culturally conservative white Catholics) began transitioning from their ancestral political home to the GOP. At first the Reagan breakthrough looked potentially cyclical or temporary. In 1982, Democrats made some midterm gains as the nation wallowed in a recession that the Fed had engineered to kill inflation, but they fell short of re-flipping the Senate, which was the big party goal. But in 1984, Reagan carried 49 states and won the national popular vote by 18 percent. Democrats today are traumatized by Trump’s 2024 gains in New York. Ronald Reagan carried New York twice (the second time by 8 percentage points). No, Republicans didn’t actually create the “Electoral College lock” that Democrats feared after 1984, but the Reagan Revolution had enough residual steam to carry a relatively weak Vice-President George H.W. Bush to a solid presidential victory in 1988. By then Jimmy Carter’s 1976 election was beginning to look like an aberration, much as Barack Obama’s two 21st-century wins are beginning to look to some observers like a temporary interruption of a steady rightward trend.

But assuming 2024 will be another 1980 seems misguided. After the end of a global pandemic and the first real national experience with significant price inflation since the days of Jimmy Carter, Donald Trump won the national popular vote by around 2 percent (it’s 3 percent now, but is being steadily eroded by the millions of ballots still being counted in California and other western states). He will win 312 electoral votes, pretty much the same as the 306 he won in 2016 and Joe Biden won in 2020. The GOP Senate conquest was mostly the product of an insanely tilted landscape that all but guaranteed a flip; Democrats won several close Senate races (they won no close Senate races in 1980). And Republican House control, if that’s the final outcome, is mostly a continuation of the status quo. The stars have aligned for a Republican trifecta, but it’s not the sort of top-to-bottom landslide that 1980 turned out to be.

Nor is it clear any sort of long-term pro-GOP political alignment is in the works. Trump’s famous 2024 gains among Black and Latino voters are surprising, if only because of his long history of racist and anti-immigrant rhetoric. But Black and Latino defections from the Democratic Party are not anything like the wholesale abandonments the party suffered in the 1980s (continuing into the 1990s and even into the new century) among white southerners and midwestern Catholic “ethnics.”

By the end of the Reagan era, Republicans had risen to parity with Democrats after many decades as the minority party. The two parties remain in rough parity now. President-elect Trump, moreover, has run his last race. Will the GOP continue to make or hold gains in 2028, presumably under the leadership of Vice-President J.D. Vance, who is at the baby-wheels stage of his transformation into a MAGA politician? Will Republicans lose ground from the inevitable disappointments that will occur when Trump fails to bring back the economy of 2019, or the relatively stable global environment of 2019? Probably. And Democrats are likely to make some adjustments as well, just as they did after Reagan gave way to Poppy Bush. When you think about it, every Democratic presidential nominee dating back to 2008 basically inherited the nomination, one way or another. The next one will earn the opportunity, presumably after a thorough self-examination by Democrats who will soon turn from finger-pointing to something more constructive.

So there’s no reason to think we’re on the brink of Republican dominance of our political system, if only because the great power Trump and his party now enjoy will almost certainly be utilized to craft unpopular and ineffective policies. Mythology aside, even Ronald Reagan didn’t really change everything for more than a few years. So Democrats and liberal-media folk contemplating a change of careers might want to stick around for a while.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.