On the ancient plains of Ethiopia, early human relatives were already trying out different ways of being upright. If you grew up hearing about Lucy as the main star of that era, new fossil finds invite you to picture a busier scene, with at least two close cousins sharing the same landscape and solving survival in very different ways.

At a place called Woranso-Mille in the Afar region, researchers have spent years tracing layers of ancient river sands and volcanic ash. Within those rocks, they found fossils from two hominin species that lived between about 3.6 million and 3.3 million years ago. One belonged to Lucy’s species, Australopithecus afarensis. The other, Australopithecus deyiremeda, occupied the same region at the same time, only a few miles away.

The story centers on a partial foot, cataloged as BRT-VP-2/73 and nicknamed the Burtele or BRT foot. It came from sediments about 24 meters above a volcanic ash layer dated to roughly 3.47 million years ago. That same sandstone layer stretches sideways to a nearby site where jaws and teeth of A. deyiremeda were found. Matching geology and fossil features now tie the strange foot to that lesser-known species.

By comparing magnetic patterns in the rocks and precise age dates, geologists showed that these individuals lived during the same time window as nearby sites that hold Lucy’s kind, only 4.5 to 5 kilometers away. You are not looking at a single “prototype” human ancestor. You are seeing two related species that were true neighbors, both walking on two legs, yet built for different lives.

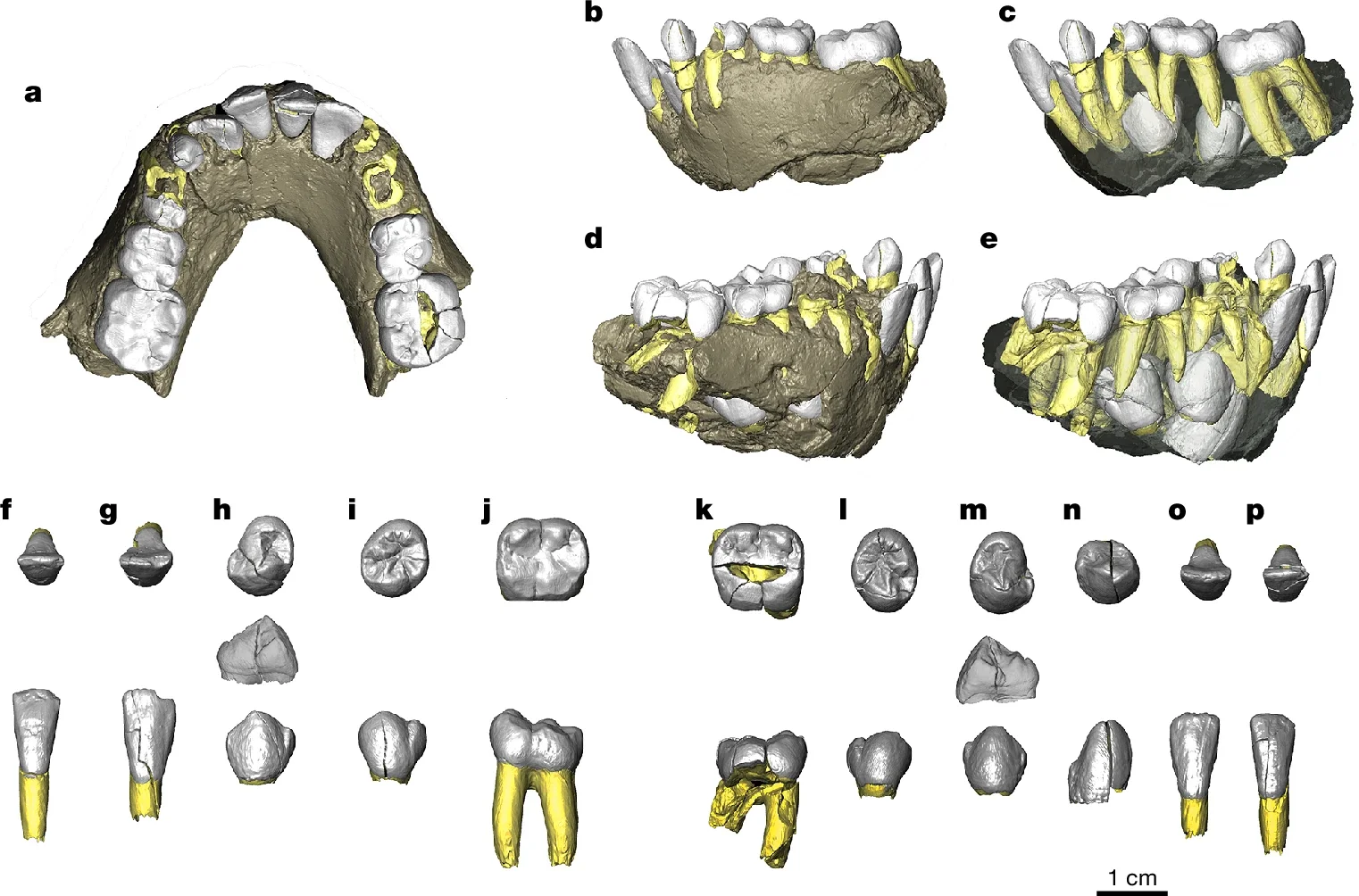

The link between the BRT foot and A. deyiremeda became much stronger when researchers uncovered a small lower jaw from a child. The fossil, labeled BRT-VP-2/135, holds a mix of baby and permanent teeth. The first adult molars had erupted and were slightly worn, but their roots were not finished forming. Using CT scans and comparisons with living apes, the team estimated that this youngster died at about 4.5 years old.

What makes this jaw so powerful is how clearly it stands apart from juvenile jaws of Lucy’s species. In A. afarensis youngsters, the outer surface of the lower jaw shows a shallow hollow on the side. That feature is completely missing in the Burtele child. Another small jaw from the same area, BRT-VP-2/258, also lacks that hollow, pointing to a different species, not just random variation.

Even small details do not match Lucy’s kind. The opening in the jaw for nerves and blood vessels sits slightly farther back. The chin region slopes more strongly. The baby molars are shaped like those of early hominins such as Australopithecus anamensis, but they are shorter and have smaller chewing surfaces than in A. afarensis. They fall outside the size range of Lucy’s species and another early hominin, Australopithecus africanus, and instead resemble more primitive relatives.

When you look at the front teeth, the story continues. The child’s permanent incisors fall within the size range of early australopiths, but the canines show a special pattern. In Lucy’s species, the inner surface of lower canines has a strong central ridge with deep grooves on each side. In A. deyiremeda, including this child, that ridge is thinner and one groove sits off to the side. Earlier work identified this “reduced relief” as a hallmark of the new species, and the Burtele fossils fit that pattern.

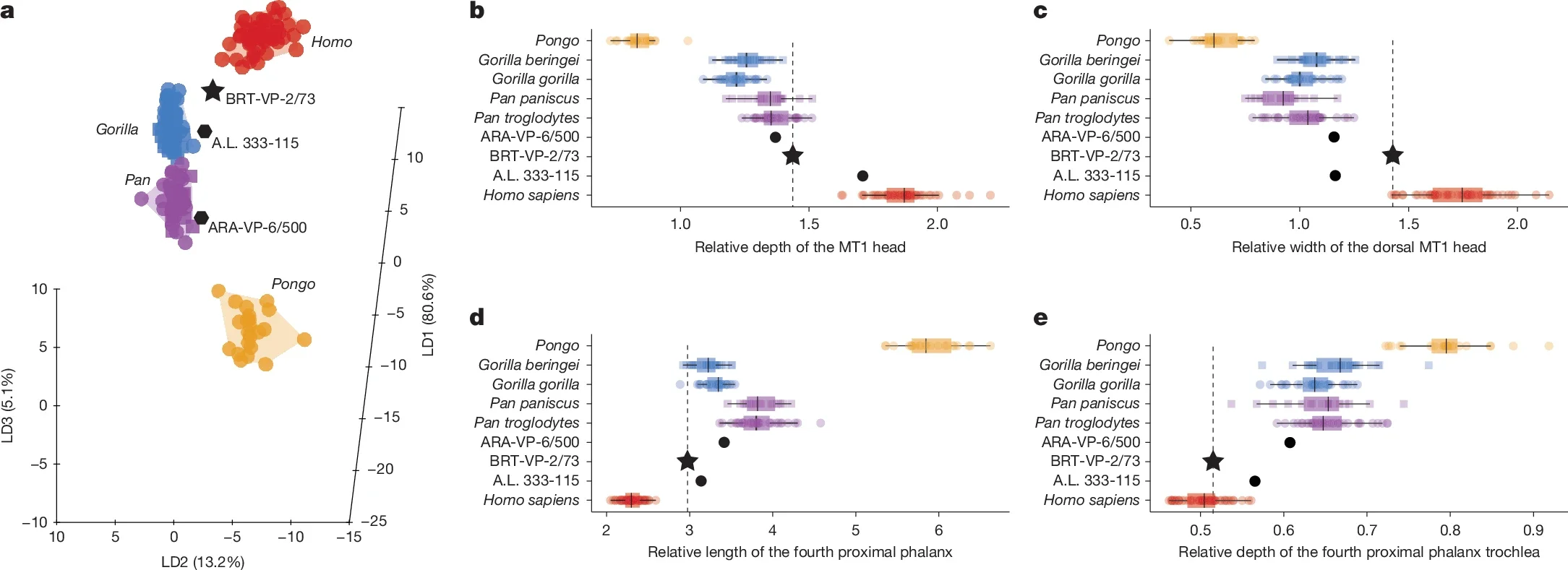

If you could hold the Burtele foot in your hands, it would feel both familiar and strange. Parts of it look closer to your own foot than the older Ardipithecus ramidus, which had a fully grasping big toe. Other traits hint that climbing still mattered a lot.

The long, curved toe bones and slender shafts of the first and second metatarsals suggest strong grasping power. The big toe was not as opposable as in Ardipithecus but more flexible than in modern humans. The head of the first metatarsal has a broad, shallow shape similar to A. africanus and different from both apes and Lucy’s species. The fourth metatarsal shows signs of a transverse arch that would stiffen the midfoot during walking, yet its shape hints that the midfoot was still more bendable than yours.

A detailed comparison of 16 measurements from early hominin feet placed the Burtele specimen and a foot from Lucy’s species closer to modern humans than to Ardipithecus. Even so, the Burtele foot keeps some gorilla-like traits in the forefoot and toe bones. It tells you that A. deyiremeda walked efficiently on two legs but kept a more flexible, grasping foot that worked well in the trees.

“When we found the foot in 2009 and announced it in 2012, we knew that it was different from Lucy’s species, Australopithecus afarensis, which is widely known from that time,” said Yohannes Haile-Selassie, director of the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University. “However, it is not common practice in our field to name a species based on postcranial elements, so we were hoping that we would find something above the neck in clear association with the foot.”

Years of new fieldwork, and fossils like the Burtele child’s jaw, finally gave the team that connection.

Knowing how these ancient relatives walked is only part of the story. To learn what they ate, the researchers looked inside their tooth enamel. Naomi Levin, a professor at the University of Michigan, sampled eight of the 25 teeth from the Burtele area for carbon isotope analysis. She used a dental drill to remove tiny amounts of enamel powder, then analyzed it in the lab.

The chemical signatures showed very low carbon isotope values, between about −12.4 and −8.8 per mille, with an average near −10.2. Those numbers point to a diet dominated by C3 plants such as leaves, fruits and shoots from trees and shrubs, rather than C4 grasses that grow in open savanna.

“I was surprised that the carbon isotope signal was so clear and so similar to the carbon isotope data from the older hominins A. ramidus and Au. anamensis,” Levin said. “I thought the distinctions between the diet of A. deyiremeda and A. afarensis would be harder to identify but the isotope data show clearly that A. deyiremeda wasn’t accessing the same range of resources as A. afarensis, which is the earliest hominin shown to make use of C4 grass-based food resources.”

At the same sites, other mammals show a wide spread of diets. Some mixed C3 and C4 foods. A fossil pig relied almost entirely on C4 grasses. In that mixed ecosystem, A. deyiremeda stuck to a more forest-focused diet, even while living right next to a cousin that ate from both wooded and grassy habitats.

The Burtele child’s jaw did not just help identify the species. It also offered a window into how these early relatives grew. Gary Schwartz, a research scientist at the Institute of Human Origins and professor in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change, used CT scans to visualize the hidden adult teeth forming inside the mandible.

The pattern showed a clear mismatch between the development of front teeth and back molars, similar to what you see in living apes and in Lucy’s kind. Some teeth were erupting early, while others lagged behind.

“For a juvenile hominin of this age, we were able to see clear traces of a disconnect in growth between the front teeth (incisors) and the back chewing teeth (molars), much like is seen in living apes and in other early australopiths, like Lucy’s species,” Schwartz said. “I think the biggest surprise was despite our growing awareness of how diverse these early australopith species were, in their size, in their diet, in their locomotor repertoires and in their anatomy, these early australopiths seem to be remarkably similar in the manner in which they grew up.”

Even as these species experimented with different diets and ways of moving, their childhood growth patterns remained much alike.

Behind every fossil in this study sits patient work in harsh field conditions. Beverly Saylor, a professor at Case Western Reserve University, led the geological effort to link each fossil to its correct layer and age. “We have done a tremendous amount of careful field work at Woranso-Mille to establish how different fossil layers relate, which is crucial to understanding when and in what settings the different species lived,” Saylor said.

That painstaking mapping made it possible to tie the foot, jaws and teeth to one another and to show that two hominin species really did share the same landscape. The Burtele foot turned out to belong to A. deyiremeda, a species with advanced jaw and face shape, smaller and more primitive teeth, a flexible, grasping foot and a forest-leaning diet.

For you, the picture that emerges is not a straight line from ape to human. Mid-Pliocene Africa held a tangle of branches. A. deyiremeda, Lucy’s species and other early relatives were all trying out different combinations of walking, climbing and eating. Bipedalism did not come in a single package. There were many ways to be upright long before your style of walking settled into place.

These discoveries do more than satisfy curiosity about ancient bones. They change how you think about human origins and how you understand change in the world today.

By showing that at least two hominin species lived side by side, used different foods and moved in different ways, this work reveals that evolution often explores many paths at once. That helps scientists build better models of how new species arise and persist without instantly wiping each other out. It also reminds you that your own lineage is just one branch that survived among many experiments.

“All of our research to understand past ecosystems from millions of years ago is not just about curiosity or figuring out where we came from,” Haile-Selassie said. “It is our eagerness to learn about our present and the future as well.”

“If we don’t understand our past, we can’t fully understand the present or our future. What happened in the past, we see it happening today,” he said. “In a lot of ways, the climate change that we see today has happened so many times during the times of Lucy and A. deyiremeda. What we learn from that time could actually help us mitigate some of the worst outcomes of climate change today.”

By tying fossil evidence to ancient climates and environments, this research gives you a deep-time view of how species responded to shifting temperatures, rainfall and landscapes. That perspective can guide modern scientists as they test which traits allow species to adapt, which push them toward extinction and how changing ecosystems reshape communities.

Future work on A. deyiremeda and its neighbors will refine growth timelines, diet details and locomotion, which can sharpen your understanding of how and when key human traits emerged. In the long run, these insights may help educators teach evolution in a more accurate and engaging way, help conservation planners think about resilience over longer time scales and help all of us see our place in Earth’s history with more humility and care.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Two ancient cousins of Lucy walked on two legs in different ways appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.