A massive volcanic eruption can cool the planet within months. What happens next may take centuries.

Currently, this potential consequence is a large part of current research being conducted on the Earth’s climate system, focusing on the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). A subset of ocean currents, the AMOC distributes and redistributes heat across the Northern Atlantic Ocean, which helps to maintain a relatively mild climate in Northern Europe.

If there is a weakening or collapse of the AMOC in the future, there will likely be a drastic change in the climate of this area and other areas connected to the AMOC.

An international team of scientists, including teams from the Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen, conducted research to determine if volcanic eruptions act as a driving force for more expansive changes within the AMOC coordinate system. Their results suggest that the AMOC is likely far more responsive to disturbances from outside forces than was previously realized.

According to Professor Markus Jochum, the lead author of this study, “The results of this research indicate that the AMOC is likely to be far more sensitive to disruptions from outside forces (e.g., volcanic eruptions) than was previously understood. This provides an important insight into the future reactions of the AMOC.”

Additionally, researchers used evidence from abrupt swings in the climate in the past as a guide to how severe the effects of volcanic eruptions will likely be in the future.

The link between volcanic activity and abrupt climate swings has been known for many years. During the period from approximately 115,000 years ago to 11,700 years ago, the Earth experienced multiple periods of sudden warming and cooling that occurred over hundreds to thousands of years. These rapid transitions are referred to as Dansgaard–Oeschger events and were associated with temperature changes of roughly 10 to 15 degrees Celsius (33 to 59 degrees Fahrenheit) in Greenland in only a few decades.

Researchers have been able to demonstrate that these abrupt temperature shifts were driven by fluctuations in the AMOC. After strengthening, the circulation allowed heat to migrate northward, and the resulting rise in temperature occurred quickly. Conversely, once the circulation weakened, the cold returned again.

According to Dr. Guido Vettoretti, who is also affiliated with the Niels Bohr Institute, he and others have proposed the idea that occurrences of large eruptions may serve to provide the impetus needed for a tipping point to occur in this system.

“We demonstrate that in the past, the eruption of large volcanic eruptions situated near the equator caused a collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation that led to abrupt climate change on a time frame of thousands of years,” said Dr. Vettoretti.

To investigate the above-mentioned hypothesis, the researchers used ice cores and compared them to simulations derived from highly detailed climate models.

Large eruptions eject sulfur dioxide, ash, and dust into the atmosphere. Ash and silt particles reflect sunlight away from Earth, resulting in cooler global temperatures.

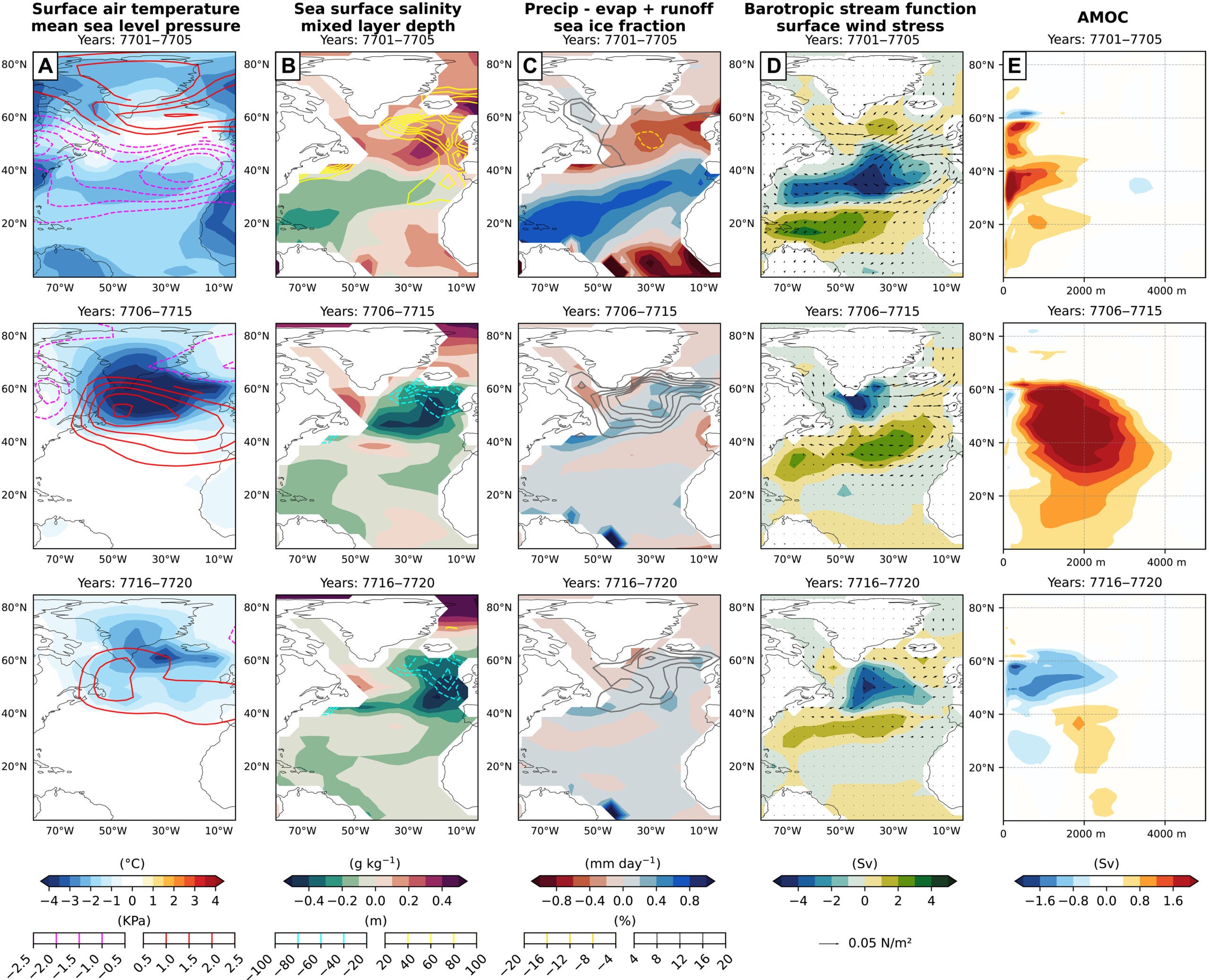

The output from climate model simulations supports a chain reaction occurring over time.

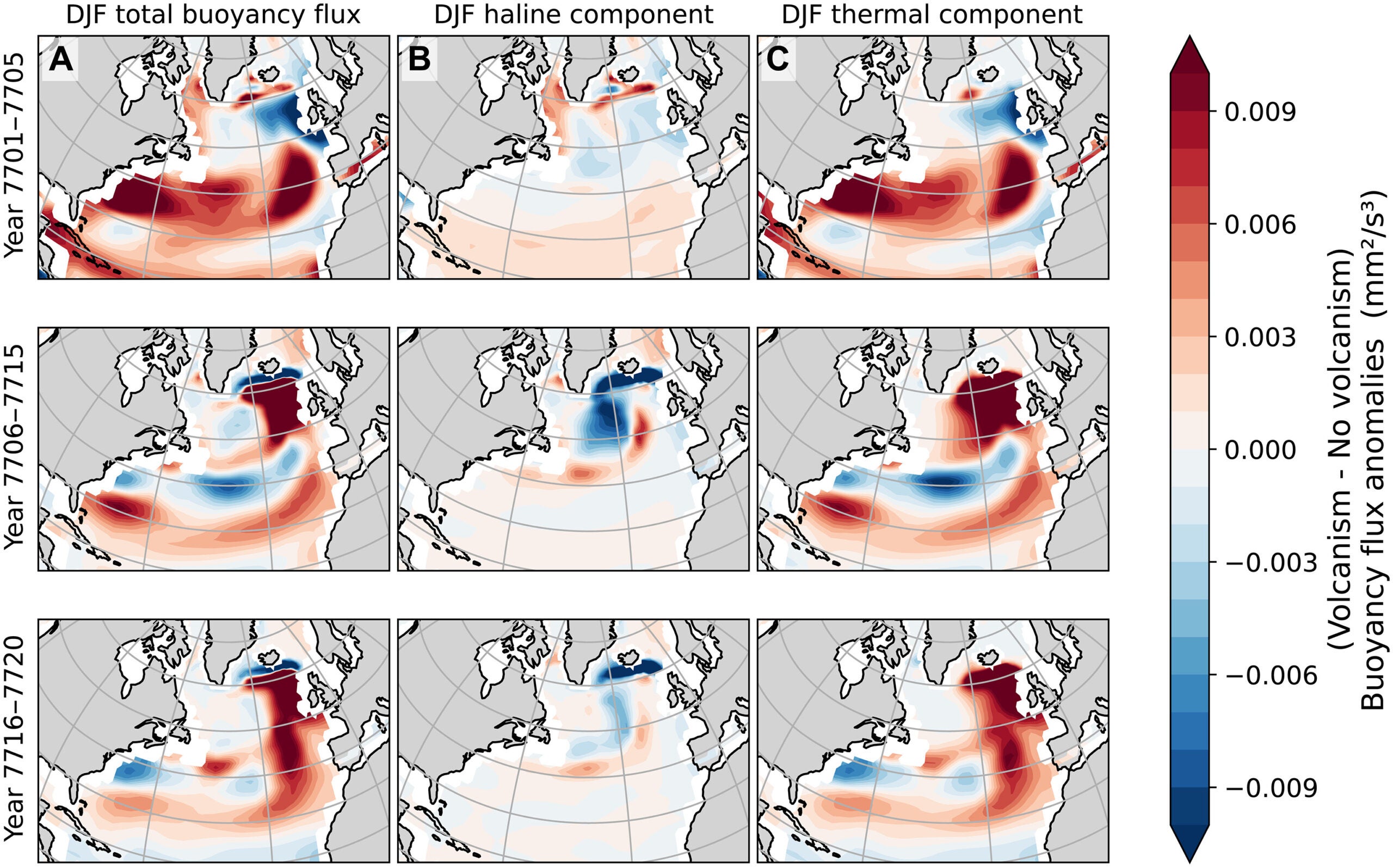

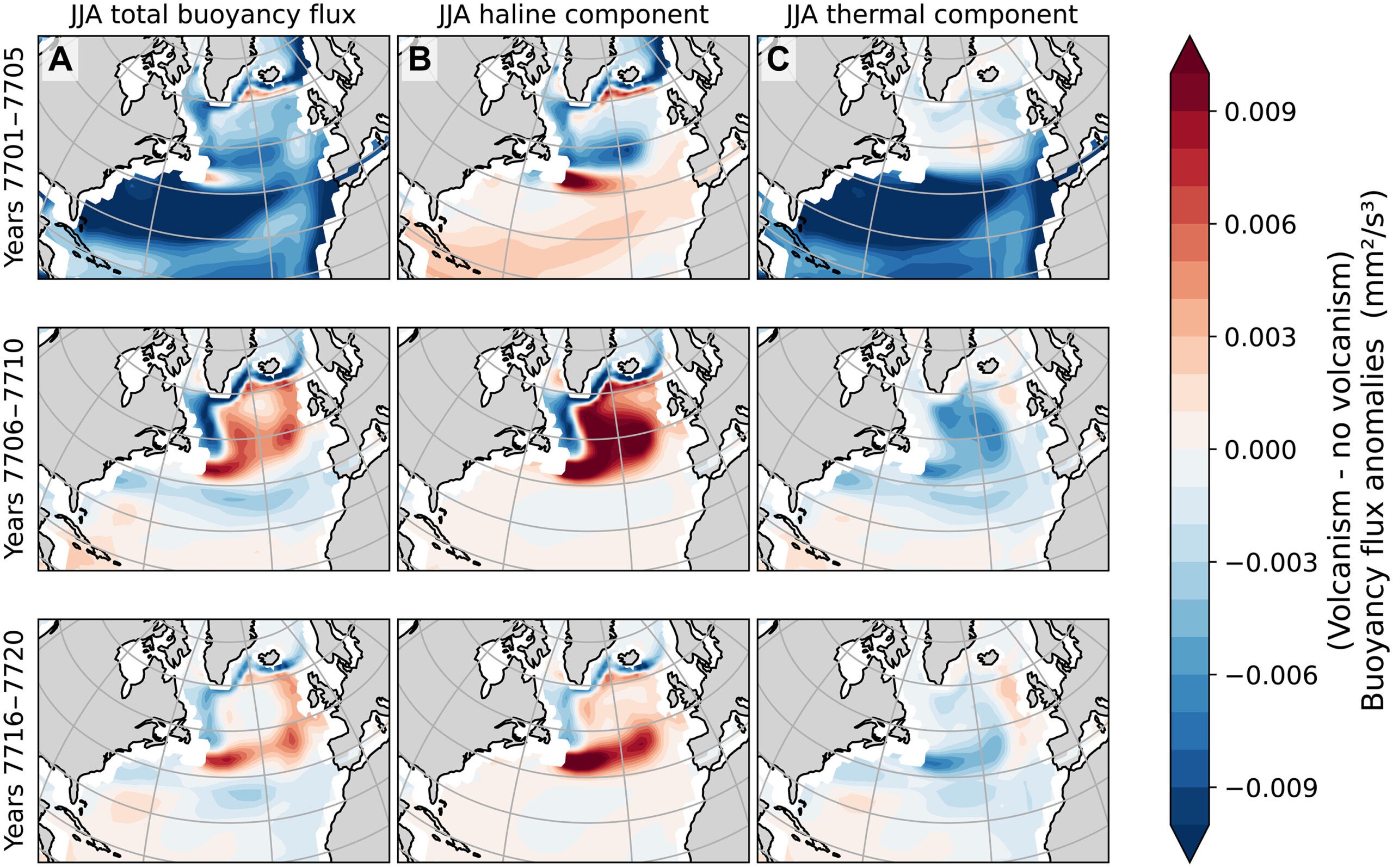

Cooling impacts the formation of sea ice in the North Atlantic, along with changes in the balance of salinity of the surface ocean waters. This is important because the AMOC is dependent on the sinking of dense and salty seawater occurring at high latitudes. Changes in salinity and the formation of ice have an adverse effect on the sinking of dense water and the overall strength of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. Therefore, a cooler atmosphere results in a weakening of this circulation.

Model simulations also predict a more complex, short-term response to an eruption. In the first years following an eruption, the AMOC may experience strengthening over time. It will eventually return to its stable state approximately two decades later.

The temporary increase in strength may be linked to an alteration of atmospheric circulation patterns, which results in a change similar to that of a negative North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) pattern. Reduced precipitation and runoff increase surface salinity in key locations and enhance deep-water formation on the one hand. However, expanding sea ice and additional freshwater input create a more stable surface layer that ultimately suppresses ocean mixing and results in its breakdown.

Some simulations dipped into a long-term cold state after tipping points. Other simulations were able to recover.

This trend reflected how the outcome of climate variability is affected by a complex interplay of internal and external climate forcing.

A surprising revelation from this study was that volcanic forcing does not always generate a significant climate response. The magnitude of any volcanic response is largely predicated on the “background conditions” at the time of the eruption.

The researchers concluded that the Earth’s climate system behaves similarly to a balance board close to the tipping point. When an object is on a balance board, even a small infusion of energy can flip the board over.

“It’s comparable to utilizing a balance board: if something is near the brink of losing balance, even a minuscule amount of assistance may be enough to flip it over. Our simulation illustrates how a volcanic eruption (or an analogous disturbance) can serve as that minimal push,” according to Jochum.

Utilizing the CCSM4 climate model, the authors performed multi-century simulations on glacial Earth conditions. The biggest eruption produced global cooling of approximately 2.5 °C shortly after the event.

Smaller eruptions, including the 1991 Pinatubo eruption, had almost no lasting climatic impact. Once volcanic forcing reached levels similar to the Pinatubo eruption, climatic impacts became indistinguishable from normal variability.

The authors concluded that only exceptionally large eruptions may cause major circulation changes.

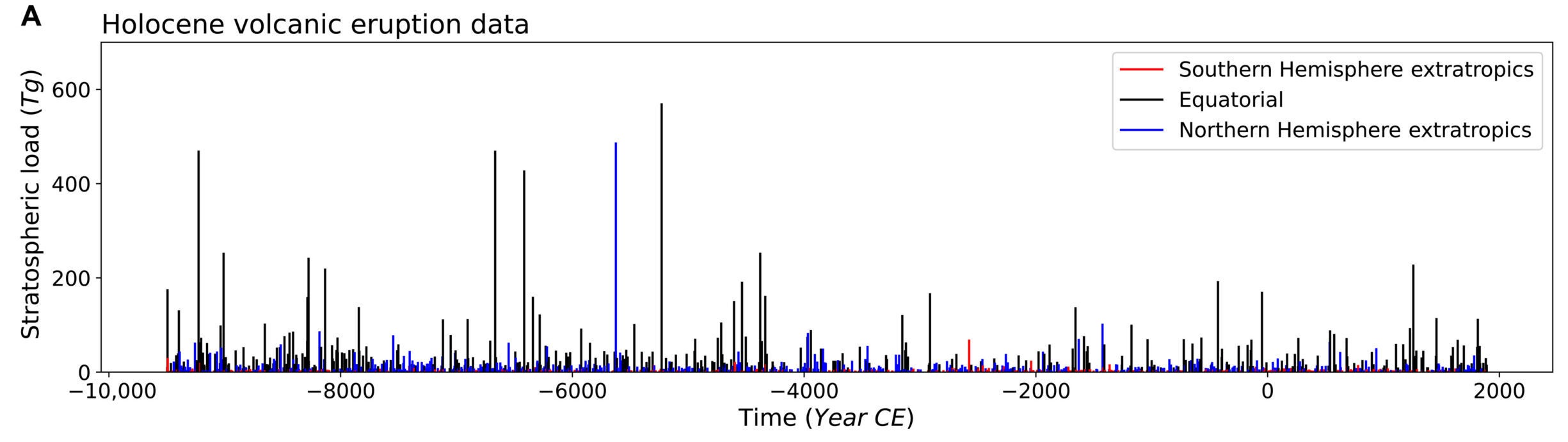

Ice cores provided the evidential data for estimating the size and number of eruptions. Ice core records provide evidence for both the presence of climate indicators and the layers of sulfates produced by many eruptions, which allows for determining the timing of eruptions versus environmental conditions.

Despite the usefulness of ice core evidence, the authors recognized that there are numerous uncertainties surrounding the reliability of such data. Ice core evidence is impacted by several factors, including the precision of dating methods, incomplete volcanic data, and currently unknown sulfur emissions produced by ancient eruptions. As a result, large volcanic eruptions may be unrecorded in geological history.

Climate model simulations cannot accurately reproduce every climate condition that existed prior to the inception of climate modeling due to differences between ice sheets and atmospheric circulation during glaciation periods.

The authors reiterated that additional research is required, specifically examining the cumulative impacts of multiple eruptions over longer periods rather than the impacts of single eruptions.

AMOC is a significant concern for contemporary climate modeling.

Melting ice and precipitation from storms as a result of rapid, large-scale climate change could impact the AMOC during this century. Certain recent studies indicate a shutdown scenario is possible, but others continue to debate the probable timing of a feedback loop.

The evidence provided by the research does not imply that future volcanic eruptions will lead to the breakdown of the AMOC. Rather, the evidence illustrates how the combination of environmental shocks and fluctuations can interact to produce climatic change.

Researchers believe that improved understanding of these interactions will assist scientists in predicting future risk factors.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science.

The original story “Volcanic eruptions in the distant past may have led to ocean current collapse” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Volcanic eruptions in the distant past may have led to ocean current collapse appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.