Public health experts in the United States have argued over the past several years that voting may be associated with well-being. The idea gained momentum as federal programs and medical organizations began calling civic engagement a “social determinant of health.”

However, the evidence has not always been robust. Many earlier studies relied on self-reported surveys that are subject to memory error or social pressure to respond positively. Now, a new study from Finland ends up providing one of the more robust views at how voting relates to long-term health.

Researchers followed over 3.1 million adults eligible to vote in the Finnish parliamentary elections of 1999 and then subsequently tracked their mortality for over 21 years. Because Finland maintains a national record that is meticulous, the research team was able to connect official voter lists with population registers, educational attainment, income records, and death certificates. The result was a large sample spanning over 58 million person-years.

Among adults 30 and older, turnout was just over 71 percent for men and over 72 percent for women. By the end of 2020, there were over one million deaths of individuals in the group. The research team then employed a commonly used statistical method called a Cox model to estimate the relationship between voting and mortality, controlling for age, education, and socioeconomic information.

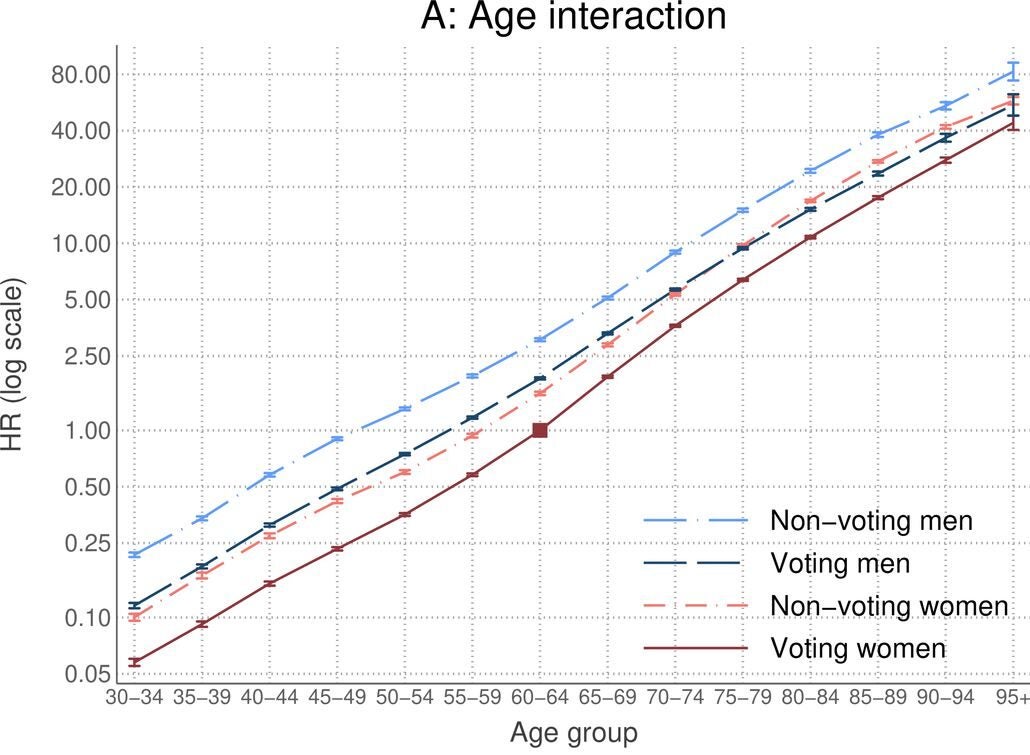

The results were as eye-opening as they were obvious. Adults who did not participate in the election of 1999 experienced a much greater likelihood of dying in the following 20 years as compared to those who voted. After factoring for age, non-voting men had a 73% greater mortality risk, and non-voting women had a 63% greater mortality risk.

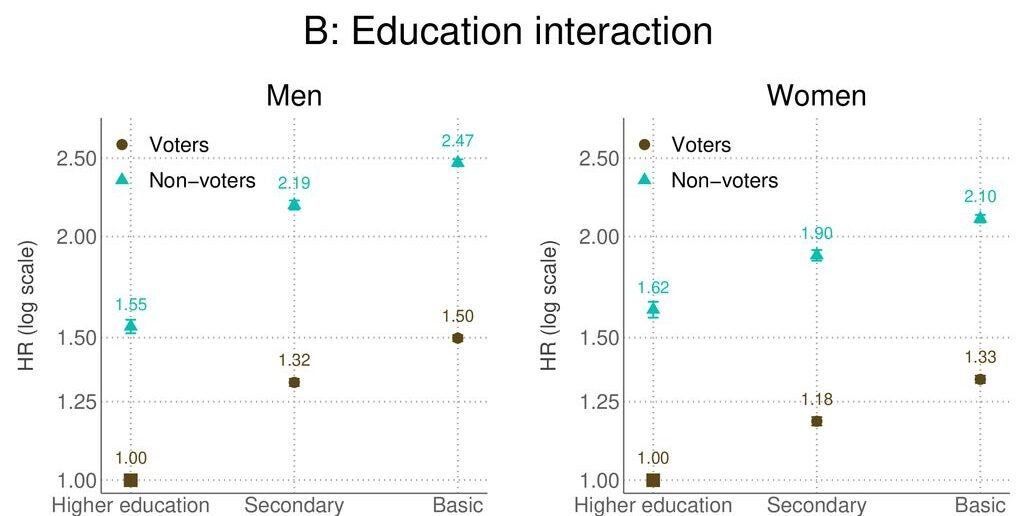

When education was included in the model, the association with risk was diminished, but remained large; non-voting men had a 64% greater risk, and non-voting women had a 59% greater risk when education was included in the model.

The magnitude of the association surprised the research team. The difference in survival between voters and non-voters was greater than the difference in survival between people with low education and high education. This is particularly important because the education–mortality association is one of the most population health research.

The research team also looked at how various causes of death played a role in the associations. The associations were strongest for external causes of death, such as accidents, violent injuries, and alcohol-related causes. Men who did not vote were over twice as likely to die from external causes compared to those who voted. Women who did not vote also experienced the same twofold greater risk from external causes.

When examined in shorter-term time frames using the first five years and ten years following the election, there were even stronger differences found between those who voted and those who did not vote. This pattern points to the possibility that health concerns simultaneously measured at the time of the election may affect both voting behavior and short-term survival.

Age mattered. The disparity between voters and non-voters was largest among adults younger than 50 years old. For older adults, especially those aged 75-94 years, women who did not vote had higher mortality than their male counterparts.

Income also shaped the patterns. For men in the lowest quarter of household incomes, the gap between voters and non-voters widened by some 12 percent compared to higher income groups. Among women in the upper non-manual occupational group, the difference increased as much as 11 percent compared to other social classes.

These differences were apparent because of the size of the dataset. Even small differences were statistically significant, but this limited the interpretation about social class: spending time voting and engaging in civic matters is associated with longevity across a range of circumstances.

The study does not establish that voting is health protective. Healthier people may simply be more able or willing to participate in elections. Being ill, disabled, or chronically ill may make it harder for someone to follow political issues, travel to the polling places, or feel engaged in civic life.

Voting can be viewed as a type of social engagement, and studies often identify participation with stronger social networks and connections, a greater sense of meaning and life purpose, in addition to increased mental and physical health. When citizens engage in the act of voting, they may signal broader and deeper social connections and stability that influence health throughout the lifespan.

The authors further discuss the potential value in observing retirees or individuals with lifelong voting habits abandon voting habits, as this may reflect the onset of health problems. The authors note that health providers can observe changes in civic participation patterns as markers when working with patients.

On a population health level, the patterns also raise questions related to concerns for ‘equitable democratic representation.’ If higher health-risk groups engage in civic participation patterns that collectivize voting behavior less often, it could mean their needs are less often represented in democratic societies.

This long-term examination presents a rare opportunity to observe how a rather simple civic engagement behavior can pattern with the outcomes of life and death over several decades. Although the question of causation is still open, the study clearly suggests that voting fits within an even larger context of social and economic constructs that make up health behavior. This work adds weight to the argument that civic behavior belongs in the spectrum of public health research on health and communities.

The findings suggest a continued, deeper view of civic life, voting specifically. When large gaps in mortality reflect participation gaps in higher health-risk groups such as people with mental health conditions, it suggests that society doesn’t have a full perspective on understanding and meeting the needs or lives of the people who are struggling the most in society. Improving health risk may also improve the representation of certain populations in the political arena.

The findings may stimulate public health teams to investigate civic behaviors as a valid early marker of an at-risk health decline.

One day, doctors might inquire about civic participation behaviors in a fashion somewhat like they ask about sleep, physical activity, or dietary habits.

Furthermore, the study demonstrates that closing health gaps can aid in participating more in elections, thus leading to visibility with political representation and more equitable policy.

Research findings are available online in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Voting behavior strongly linked to future risk of death, study finds appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.