Keeping track of time seems simple. A watch ticks, a pendulum swings, and a calendar flips. But at the quantum level, marking time is far more complicated — and far more expensive than anyone expected. New research from the University of Oxford shows that reading a quantum clock uses vastly more energy than running the clock itself. The findings could reshape how future quantum technologies are built and understood.

At everyday scales, clocks rely on processes that cannot be reversed, like the swing of a pendulum or the vibrations of atoms in an atomic clock. These processes naturally mark the passage of time. At the quantum scale, however, such irreversible steps are minimal or absent, making timekeeping much trickier.

For technologies that depend on highly precise clocks, like quantum computers or navigation systems, understanding the energy needed to keep and read time is crucial. Until now, the thermodynamics of quantum clocks remained largely a mystery.

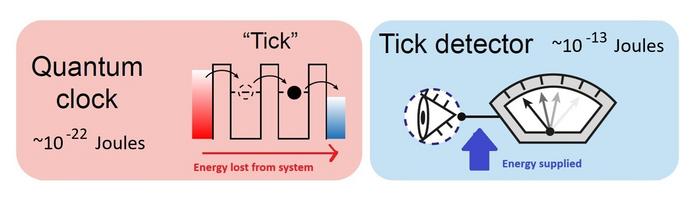

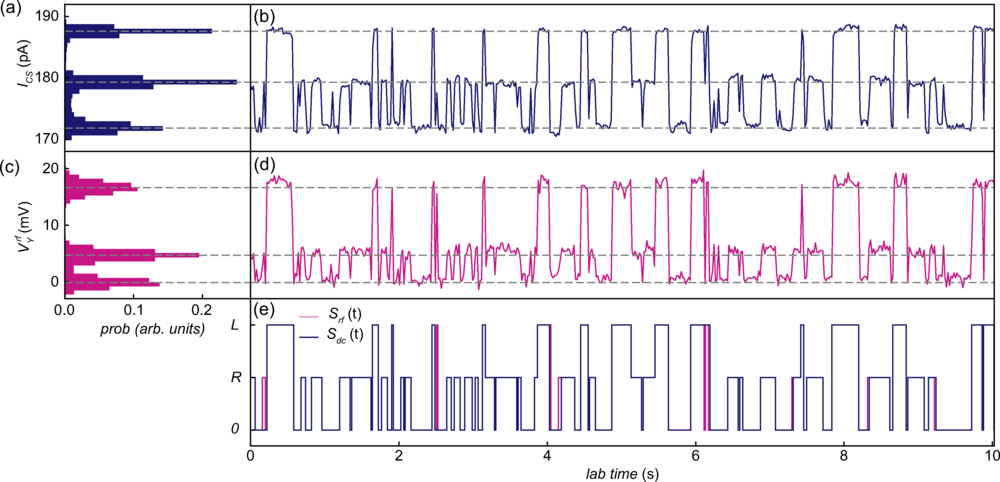

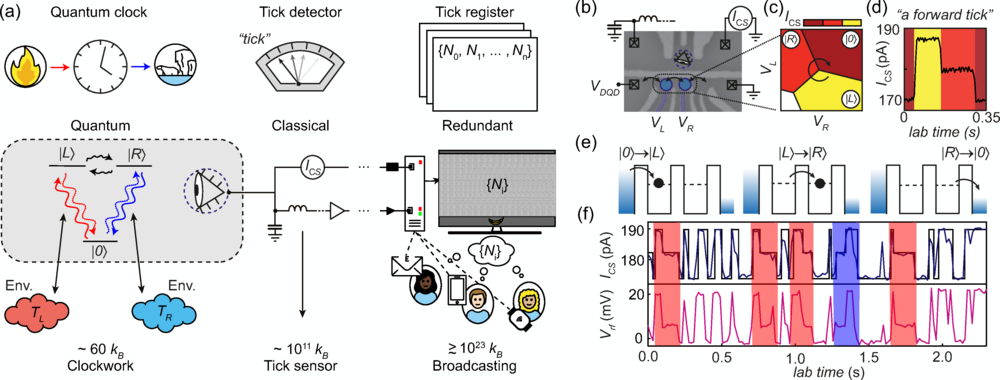

Researchers at Oxford asked a simple but profound question: what costs more energy — running a quantum clock, or observing it? To find out, they built a microscopic clock using a double quantum dot, two tiny regions that can trap individual electrons. When an electron jumps between these regions, it acts like a “tick” of the clock.

To detect these jumps, the team used two methods. One measured minute electrical currents, while the other tracked changes with radio waves. Both methods converted the quantum events — the electron jumps — into classical data that humans or computers can read. This transition from quantum to classical is where the real energy expense comes in.

Lead author Professor Natalia Ares, from Oxford’s Department of Engineering Science, explained, “Quantum clocks running at the smallest scales were expected to lower the energy cost of timekeeping, but our new experiment reveals a surprising twist. Instead, in quantum clocks, the quantum ticks far exceed that of the clockwork itself.”

The double quantum dot acts as the heart of the quantum clock. Each dot can hold a single electron, and electrons tunnel back and forth unpredictably. Yet the rate of tunneling can be measured reliably, creating a precise clock signal. The team tracked each tick using a charge sensor, which detects when an electron leaves one dot and enters the other.

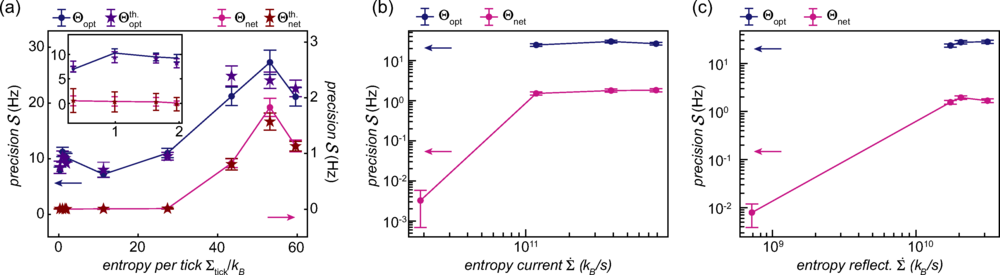

The researchers carefully measured the energy used both by the quantum dot system itself and by the sensors that recorded the ticks. They also tested two readout methods — direct electrical measurement and a radio-frequency approach — to see how different techniques affected energy use. Their calculations revealed that the entropy generated by measurement and amplification was up to a billion times larger than the energy needed to move the electrons. In other words, reading the clock costs far more than running it.

Co-author Vivek Wadhia, a PhD student at Oxford, said, “Our results suggest that the entropy produced by the amplification and measurement of a clock’s ticks, which has often been ignored, is the most important thermodynamic cost of timekeeping at the quantum scale.”

The findings also shed light on a deeper question in physics: why does time move in one direction? Florian Meier, a PhD student at Technische Universität Wien, explained to The Brighter Side of News, “By showing that it is the act of measuring — not just the ticking itself — that gives time its forward direction, these findings link the physics of energy to the science of information.”

“Essentially, the very act of observation makes the passage of time irreversible. Without measurement, the ticks exist in the quantum world but leave no record, meaning time cannot be tracked in a classical sense. Measurement is not just passive; it actively shapes how we experience time,” he added.

Interestingly, the extra energy spent on measurement is not a flaw. It can improve precision by giving a detailed record of each tick. Rather than just counting time, scientists can analyze every small change, leading to more accurate and reliable clocks. However, this higher precision comes at the cost of greater energy consumption, highlighting a trade-off between accuracy and efficiency.

This discovery carries profound implications for the design of future quantum devices. Quantum computers, sensors, and communication systems all rely on precise timing. If measuring the clock’s ticks consumes far more energy than generating them, engineers must rethink how clocks are built and read at the quantum scale.

The research shows that the energy cost of measurement cannot be ignored, overturning assumptions in quantum thermodynamics. Until now, scientists often focused on making the clockwork more efficient, assuming the readout would be negligible. This study proves the opposite: the sensors and amplification systems dominate energy expenditure.

Professor Ares emphasized, “Efforts to make quantum clocks more efficient should focus on smarter, energy-efficient ways to measure the ticks, not just improving the quantum system itself.”

Beyond practical applications, the study also contributes to understanding fundamental physics. Timekeeping is essential to nearly all natural processes, and learning where energy is spent at the quantum level helps define the limits of precision. It also reinforces the connection between energy, entropy, and information, showing how deeply intertwined they are in the physical world.

By using a system as small as a pair of electrons, scientists can now probe the rules of quantum thermodynamics more thoroughly. The work demonstrates that measurement itself is an active player in how energy flows and how time is perceived.

The Oxford team’s work provides a roadmap for future research in quantum timekeeping and nanoscale devices. Engineers designing autonomous systems or quantum computers can use these insights to reduce energy loss while maximizing accuracy. Scientists can also explore other ways to read quantum information more efficiently, possibly revolutionizing the way we think about measurement, clocks, and energy at the smallest scales.

Ultimately, the study reminds us that even something as basic as keeping time has hidden costs. Nature does not give anything away for free, even at the level of single electrons. Understanding these costs opens the door to smarter, more sustainable quantum technologies and gives fresh insight into the very nature of time itself.

The study shows that in quantum devices, reading a clock consumes far more energy than running it. This insight will help engineers design quantum computers, sensors, and communication systems more efficiently. It also highlights the trade-off between measurement precision and energy cost.

Beyond technology, the findings deepen our understanding of time, entropy, and energy in nature. Future research could lead to autonomous, energy-efficient nanoscale devices that perform computations and keep time with minimal waste.

Research findings are available online in the journal APS.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post What costs more energy — running a quantum clock or observing it? appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.