Human cryogenics, often referred to as cryonics, is the process of preserving the human body at ultra-low temperatures after legal death, with the hope of future revival.

The concept is based on the principle that advances in medical and biotechnological sciences may one day allow for the reanimation and repair of frozen individuals.

Cryonics is distinct from general cryogenics, which is the study of materials at extremely low temperatures, and from cryotherapy, which uses cold temperatures for medical treatments.

The preservation process involves cooling the body to -196 degrees Celsius (-320 degrees Fahrenheit) using liquid nitrogen. Before freezing, a process called vitrification is used to replace bodily fluids with cryoprotectants to prevent ice crystal formation, which could damage cells.

Though the idea sounds like science fiction, there are companies actively offering cryonic preservation services, with hundreds of people already stored in cryonic facilities worldwide.

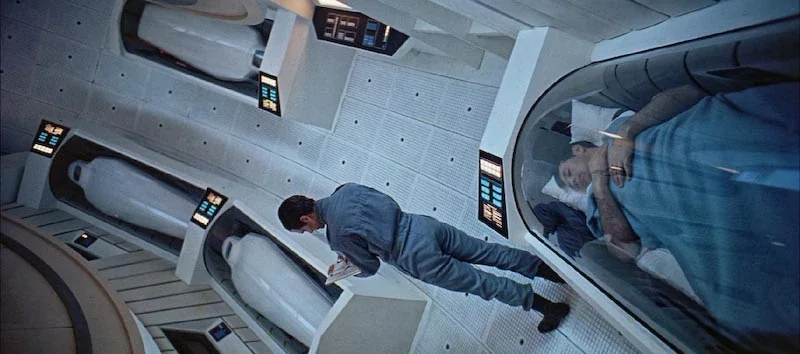

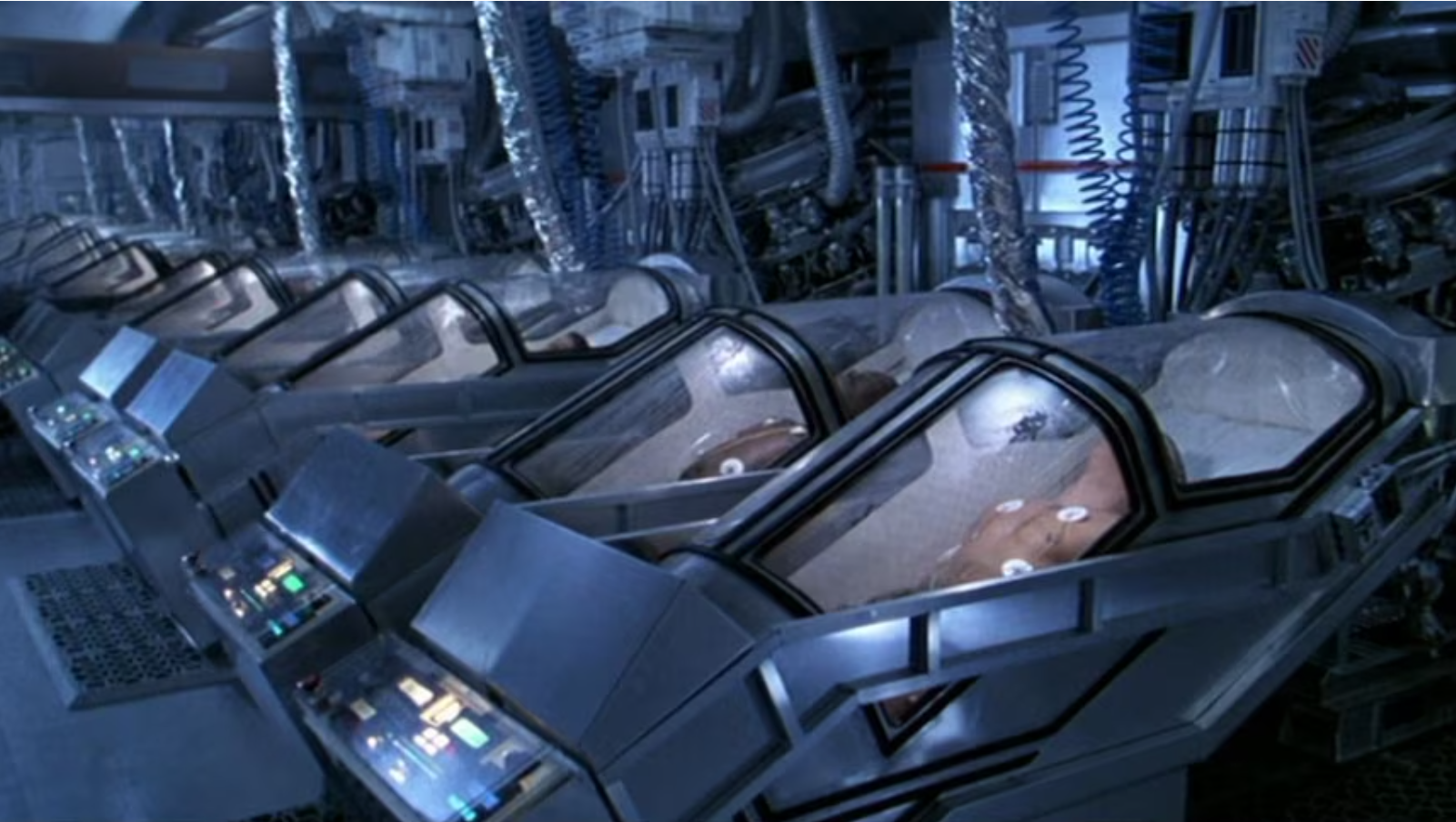

Cryonics has long captured the imagination of Hollywood and science fiction writers. Popular films and television shows have portrayed the concept in varying degrees of realism.

In 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), astronauts are placed in suspended animation for long-term space travel. Demolition Man (1993) features criminals cryogenically frozen as a form of punishment, while Vanilla Sky (2001) explores the psychological and ethical dilemmas of a man who wakes up in the future after undergoing cryogenic preservation.

More recently, Altered Carbon (2018) presents cryogenics as part of a broader transhumanist vision where consciousness can be stored and transferred between bodies. These portrayals, though often exaggerated, reflect real questions about the feasibility and ethics of cryonic suspension.

Related Stories

While Hollywood’s take on cryonics often bends reality for dramatic effect, these films help bring awareness to real scientific debates surrounding the feasibility, ethics, and future of human cryopreservation.

The idea of cryonics dates back to the 1960s when Robert Ettinger, a physicist and science fiction writer, introduced it in his book The Prospect of Immortality (1962). Ettinger later founded the Cryonics Institute in 1976, one of the world’s first organizations offering human cryopreservation services.

Scientists have long studied how freezing temperatures affect biological tissues. The earliest cryogenic studies focused on small organisms, laying the groundwork for modern cryonics. Some of the key milestones include:

2010s-Present: Advances in Cryobiology and Nanotechnology – More recent efforts in cryonics involve integrating nanotechnology and regenerative medicine. Researchers are exploring the use of nanoparticles to facilitate uniform cooling and thawing, preventing localized damage. Additionally, studies on tardigrades and wood frogs—organisms that naturally survive freezing—have provided insights into biological antifreeze proteins, which could one day be applied to human cryopreservation.

1940s-1950s: Early Cryopreservation Research – During this period, scientists began experimenting with preserving simple biological tissues at subzero temperatures. In 1947, British scientist Christopher Polge discovered that glycerol could act as a cryoprotectant, preventing ice crystal formation and cellular damage. This discovery was instrumental in later cryopreservation efforts.

1960s-1970s: Organ Preservation and First Cryonics Attempts – Scientists explored cryogenic preservation of individual organs, particularly kidneys and hearts. These studies showed that while certain small tissues could survive freezing, whole organs and complex systems suffered irreparable damage upon thawing. In 1967, Dr. James Bedford became the first person to be cryopreserved. His body remains frozen at Alcor today, though technology at the time lacked the precision and advanced cryoprotectants used today.

1980s-1990s: Vitrification and Advanced Cryoprotectants – A major breakthrough came in the 1980s when researchers introduced vitrification, a process where biological tissues are cooled to a glass-like state without ice crystal formation. In 1984, scientists Gregory Fahy and William Rall demonstrated vitrification’s effectiveness in preserving embryos, marking a turning point for cryonics research. During this time, rapid cooling and cryoprotectant infusion techniques improved, leading to the first successful vitrification of a mammalian organ.

2000s: Small Mammal Organ Revival Studies – By the early 2000s, scientists successfully vitrified and revived a rabbit kidney, which functioned normally after transplantation. This experiment, conducted by Fahy and his team, was a significant step forward, demonstrating that complex organs could be frozen and revived without significant damage. However, researchers have yet to successfully apply this process to an entire mammalian body.

Several companies today offer cryonics services to those willing to take a leap of faith into the future. The largest players in the industry include:

Founded in 1972, Alcor is one of the most well-known and advanced cryonics organizations in the world. The company currently houses over 200 cryopreserved individuals and is actively engaged in refining its preservation methods.

Alcor offers both whole-body cryopreservation and neurocryopreservation, which involves freezing just the brain. The organization is known for its meticulous vitrification process, using a proprietary cryoprotectant solution that minimizes cellular damage.

Alcor also invests heavily in research to improve revival prospects, including collaborations with nanotechnology researchers who study molecular repair techniques. With a focus on long-term sustainability, the company maintains a Patient Care Trust, ensuring funds are available for perpetual maintenance.

Established by Robert Ettinger in 1976, the Cryonics Institute (CI) is another major player in the field. CI has preserved over 100 individuals and offers one of the most affordable cryopreservation services, with whole-body preservation costing around $28,000.

Unlike Alcor, CI does not perform neurocryopreservation, opting instead for full-body storage exclusively. The organization also offers cryogenic preservation of DNA samples and pet preservation services. CI places a strong emphasis on affordability, enabling more people to access cryonics through life insurance funding options.

The institute continues to work on enhancing its storage facilities and refining preservation techniques to improve the likelihood of future revival.

As the first and only cryonics facility in Russia, KrioRus provides services to international clients and has preserved several dozen individuals.

Unlike its American counterparts, KrioRus allows families to store their loved ones at its facilities outside Moscow, with the option of maintaining open access to cryopreserved relatives. KrioRus is actively working to expand its operations in Europe and Asia, aiming to make cryonics more globally accessible.

The company is also involved in research collaborations with Russian scientists studying biostasis and potential reanimation techniques.

One of the newer entrants into the cryonics industry, Tomorrow Bio is based in Europe and is positioning itself as a technology-driven cryonics provider.

The company emphasizes rapid response teams and streamlined preservation logistics to ensure bodies are stabilized and cooled as quickly as possible. Tomorrow Bio also integrates AI-based monitoring systems to track storage conditions and optimize preservation quality.

The organization is currently expanding its European footprint, aiming to create a network of cryonics storage facilities that improve accessibility and logistical efficiency for clients worldwide.

While cryonics is advancing, significant scientific hurdles remain. The biggest challenges include:

Despite these challenges, advances in regenerative medicine, nanotechnology, and artificial intelligence could one day make reanimation feasible. Researchers are already working on organ cryopreservation techniques, and breakthroughs in brain mapping and neural preservation could pave the way for future revival methods.

Critics argue that cryonics is based more on hope than science. Bioethicist Arthur Caplan has referred to it as “selling snake oil” due to the lack of evidence for revival. Others, like MIT roboticist Ray Kurzweil, believe that exponential technological growth in fields like AI and nanotechnology will make reanimation possible within the next century.

Ultimately, cryonics is an investment in the unknown. While skeptics point out the lack of scientific validation, proponents argue that the cost of not trying could mean missing out on future medical miracles.

Whether it’s a pipe dream or a pioneering path to extended life, the frozen future of cryonics remains one of the most fascinating frontiers in modern science.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Who wants to live forever? The future of human cryogenics appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.