Children’s ability to focus their attention is an enigma that continues to intrigue scientists. While adults tend to zero in on task-relevant features, children often divide their attention across both critical and irrelevant aspects of a task.

This phenomenon, known as distributed attention, has puzzled researchers for years. What drives children to seek more information than necessary, even when they know what is required to complete a task?

A recent study sheds new light on this question. Conducted by researchers from The Ohio State University and published in Psychological Science, the study explores whether children’s distributed attention is due to immaturity in brain development or a natural tendency to explore broadly.

Surprisingly, the findings suggest that children’s attention patterns are not caused by a lack of focus or an inability to filter distractions. Instead, the behavior may stem from curiosity or underdeveloped working memory.

“Children can’t seem to stop themselves from gathering more information than they need to complete a task, even when they know exactly what they need,” explained Vladimir Sloutsky, a psychology professor at Ohio State and co-author of the study. Alongside doctoral student Qianqian Wan, Sloutsky investigated the persistent tendency of children to over-explore their environment.

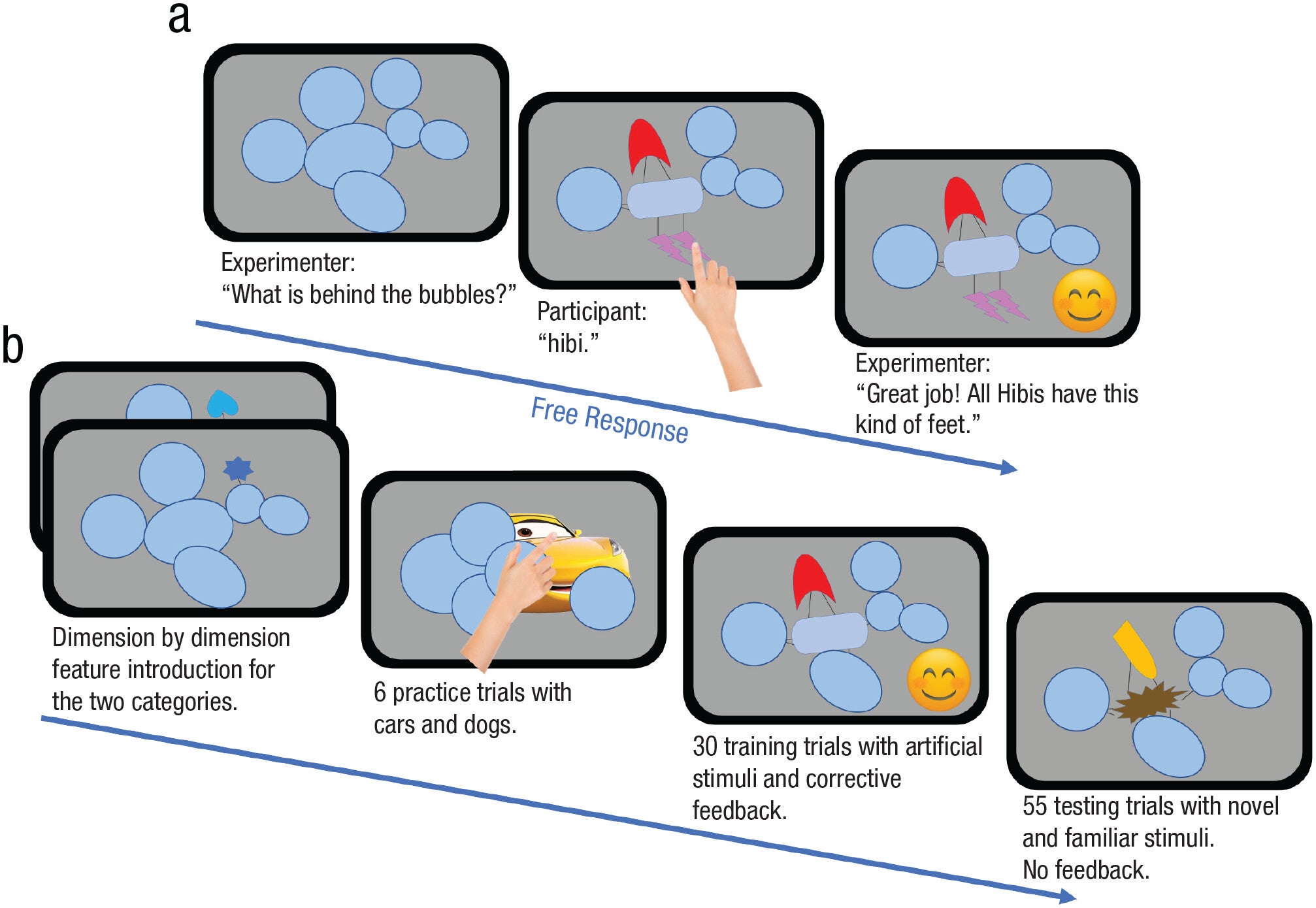

In one experiment, participants—201 individuals, including adults and children aged four to six—were asked to categorize bird-like creatures called Hibi and Gora. Each creature had unique physical features such as horns, tails, and wings.

While six of the seven features could predict a creature’s category with 66% accuracy, one feature—a specific body part—offered a perfect match every time. Both adults and children quickly learned to identify this critical feature.

Related Stories

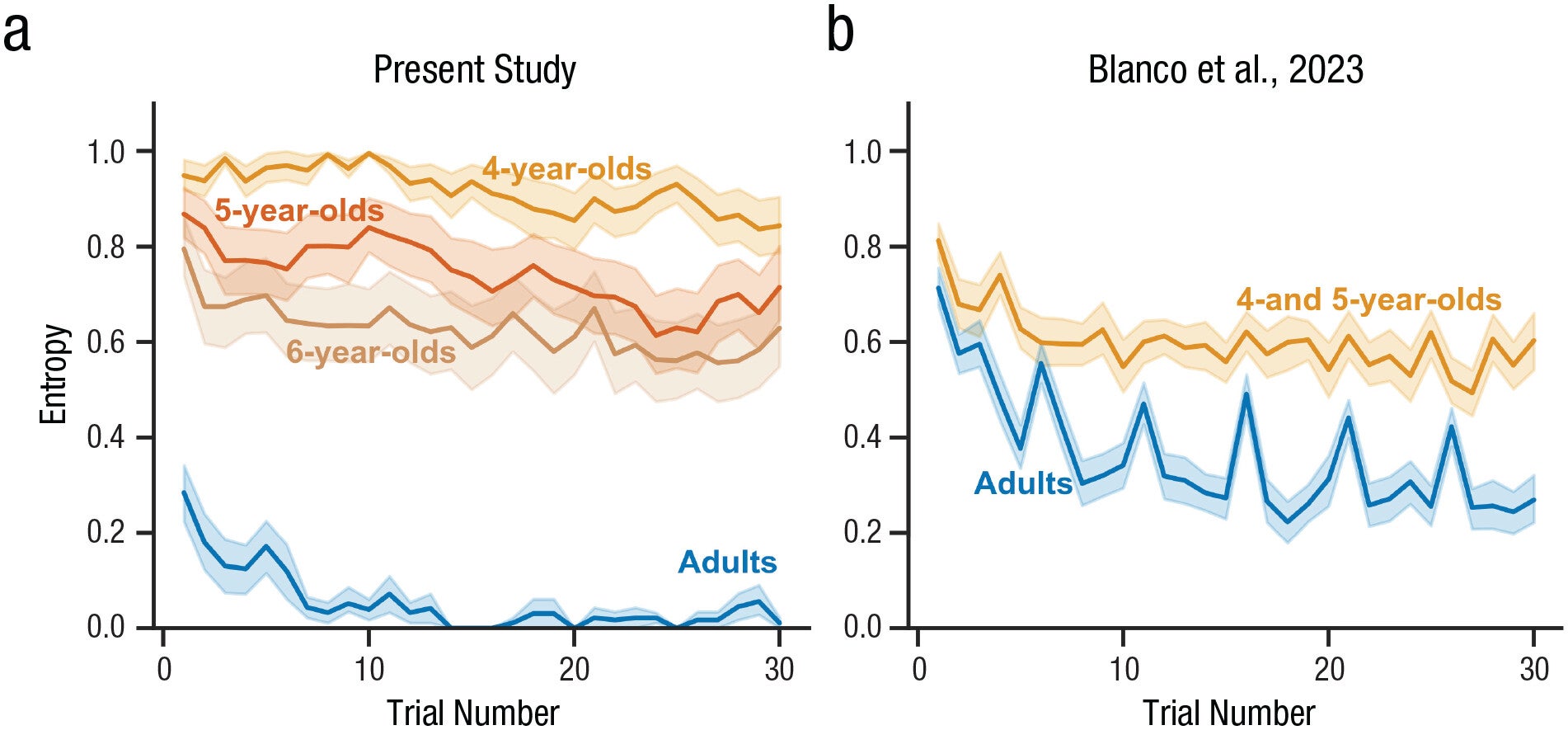

When tasked with identifying the creatures as quickly as possible, adults efficiently uncovered only the crucial feature. Children, however, behaved differently. Even when they understood which feature was the key to identification, they continued uncovering other body parts before making a decision.

“There was nothing to distract the children—everything was covered up,” Sloutsky noted. “They could have acted like the adults and only clicked on the body part that identified the creature, but they did not. They just kept uncovering more body parts before they made their choice.”

The researchers explored whether distraction could explain the children’s behavior. To remove this variable, the study ensured that all body parts were initially hidden, requiring participants to uncover features one at a time. Despite these controlled conditions, children still explored excessively.

To rule out the possibility that children simply enjoyed tapping buttons, a follow-up experiment introduced an “express” button that revealed all the creature’s features simultaneously. Children overwhelmingly chose this option, demonstrating they were not motivated by the act of clicking itself.

Sloutsky suggested two possible explanations for children’s distributed attention: curiosity and underdeveloped working memory. Children may seek additional information out of a desire to explore their environment, or they may lack confidence in their ability to remember critical details.

“The children learned that one body part would tell them what the creature is, but they may be concerned that they don’t remember correctly,” Sloutsky said. “Their working memory is still under development. They want to resolve this uncertainty by continuing to sample, by looking at other body parts to see if they line up with what they think.”

Working memory—the ability to hold and manipulate information temporarily—plays a critical role in cognitive tasks. In adults, this cognitive tool enables efficient decision-making by retaining and focusing on task-relevant details.

For children, whose working memory is still maturing, this capacity is limited. As a result, they may overcompensate by gathering excessive information to reassure themselves of their choices.

The findings open doors for further investigation into the underlying drivers of distributed attention. While working memory appears to play a significant role, researchers also plan to examine whether simple curiosity contributes to children’s behavior.

Understanding these cognitive mechanisms has broader implications for education and child development. By identifying how children process information, educators can design teaching methods that align with their natural learning tendencies. For instance, learning environments could emphasize activities that balance exploration with structured guidance.

As children grow and their working memory develops, they tend to exhibit more adult-like attention patterns. They gain confidence in their ability to focus on relevant details, reducing the need for excessive exploration. However, fostering curiosity remains essential, as it is a cornerstone of innovation and creativity.

This study offers valuable insights into the cognitive world of children, highlighting the delicate interplay between exploration, memory, and learning. As researchers continue to unravel these mysteries, they pave the way for a deeper understanding of how young minds navigate their environments.

Note: Materials provided above by The Brighter Side of News. Content may be edited for style and length.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Why children can’t pay attention and stay focused appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.