Every day, messages fly back and forth across phones with little thought. People answer friends, family, and coworkers, often with strong beliefs about how they behave. Some feel they always reply late. Others think they dominate conversations or stay online all day. A new study from Bielefeld University shows that these beliefs often miss the mark. More important, it shows that simple, personalized data can help people see their own habits more clearly, without harming their mood.

This research is led by Olya Hakobyan with Professor Hanna Drimalla. It uses anonymized WhatsApp metadata to compare what people think they do with what they actually do. The work does not read message content. It looks only at patterns such as response times and message length. That choice protects privacy while still revealing behavior.

Digital communication shapes daily life, yet self-knowledge about it remains thin. “Some believe they reply too slowly, others think they always write more than everyone else. Our data show that these assumptions are often inaccurate,” Hakobyan said. The study asks a simple question with broad impact: can clear, personal feedback replace guesswork with understanding?

For years, research on messaging relied mostly on surveys. People reported how fast they think they reply or how active they believe they are. Those reports are easy to collect, but they can be unreliable. Memory fades. Feelings distort. A late reply during a stressful week can color a person’s view of months of normal behavior.

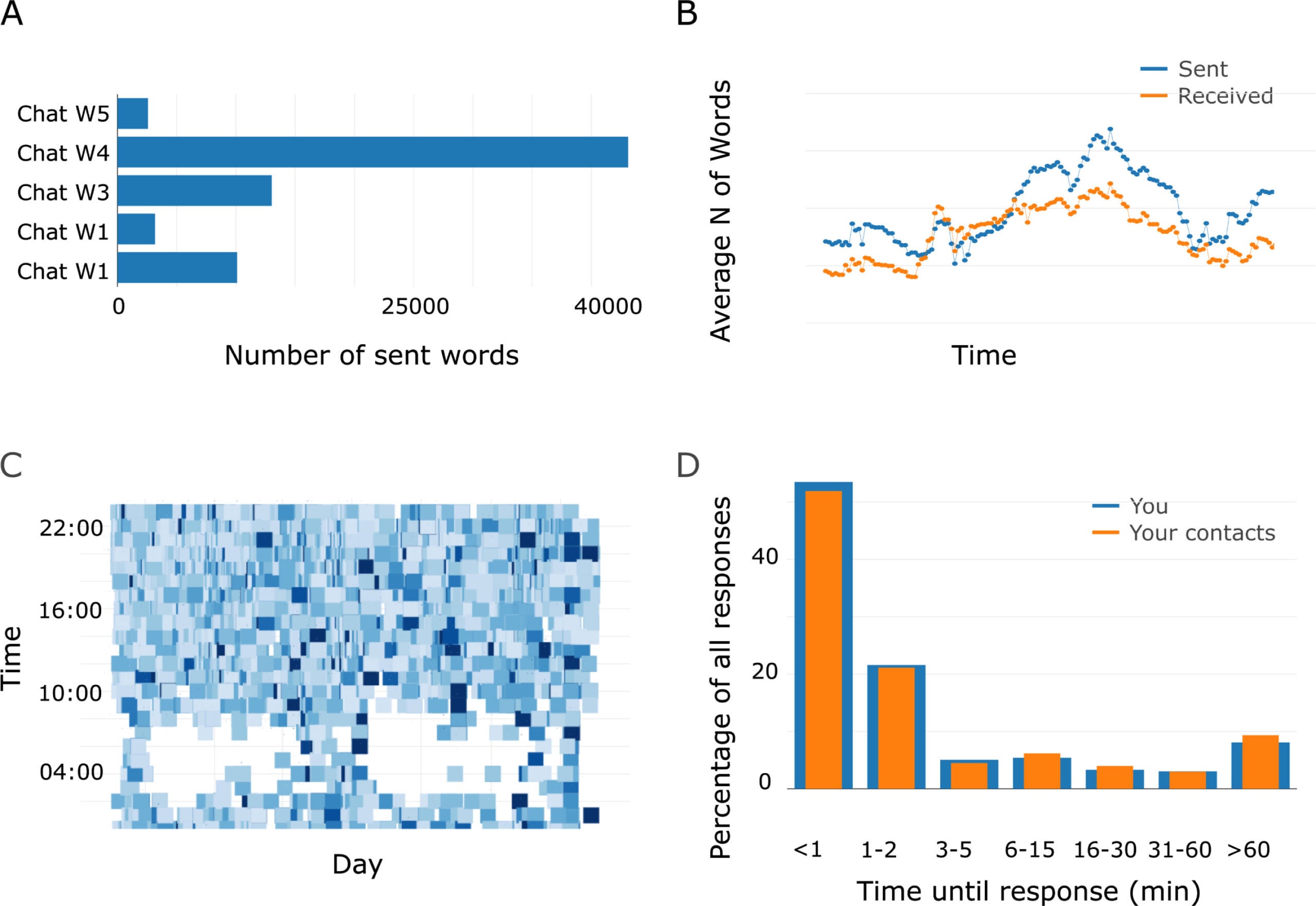

To move past that problem, the Bielefeld team built a data donation platform. It collects and anonymizes WhatsApp metadata. The platform then creates individual visualizations for each participant. The visuals show patterns such as average response time, how much a person writes compared with their partners, and how activity changes across the day.

Participants could see their own behavior at a glance. They could also compare that picture with what they had believed before. This design made it possible to test whether data-based feedback can correct misperceptions.

The study focused on metadata only. It did not collect message text. That choice reduced privacy risks and made participation more comfortable. It also kept attention on behavior patterns rather than on what people said.

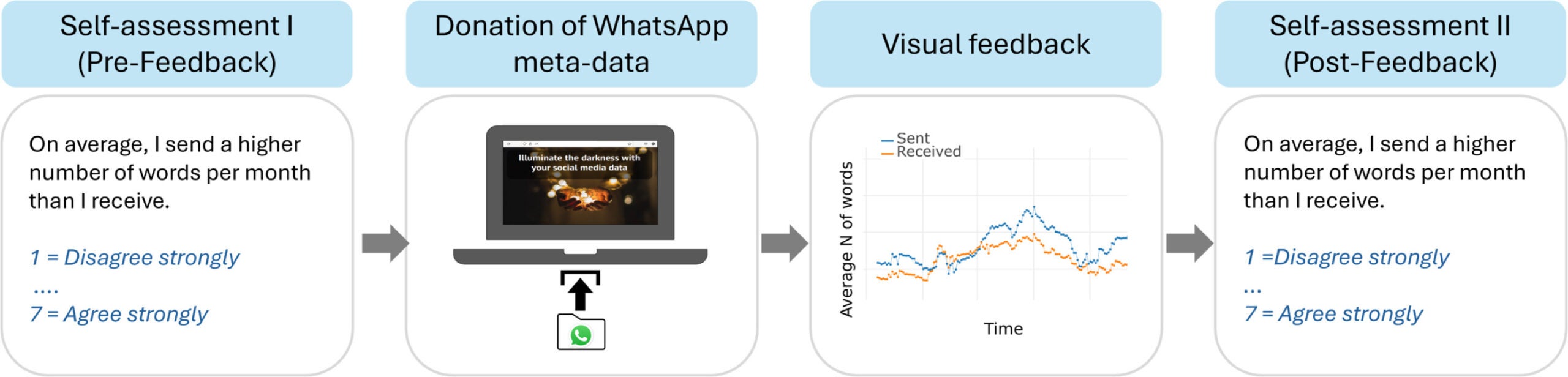

The team invited adults to take part and asked them to donate WhatsApp metadata through the platform. The dataset covered hundreds of chats across many days. Each participant first completed a survey about their own habits. They rated how fast they thought they reply, how much they contribute to conversations, when they are most active, and how evenly they spread messages across chats.

After that, participants received personalized charts based on their own data. The charts did not judge or score. They simply showed patterns. Then participants answered the same questions again.

This before-and-after design made change visible. If someone believed they reply very fast but the chart showed long gaps, would their view shift? If someone felt they always write more than others but the chart showed balance, would they update that belief?

The researchers also tracked mood before and after feedback. They wanted to know whether confronting reality would feel bad. That concern matters for any tool meant to improve digital well-being.

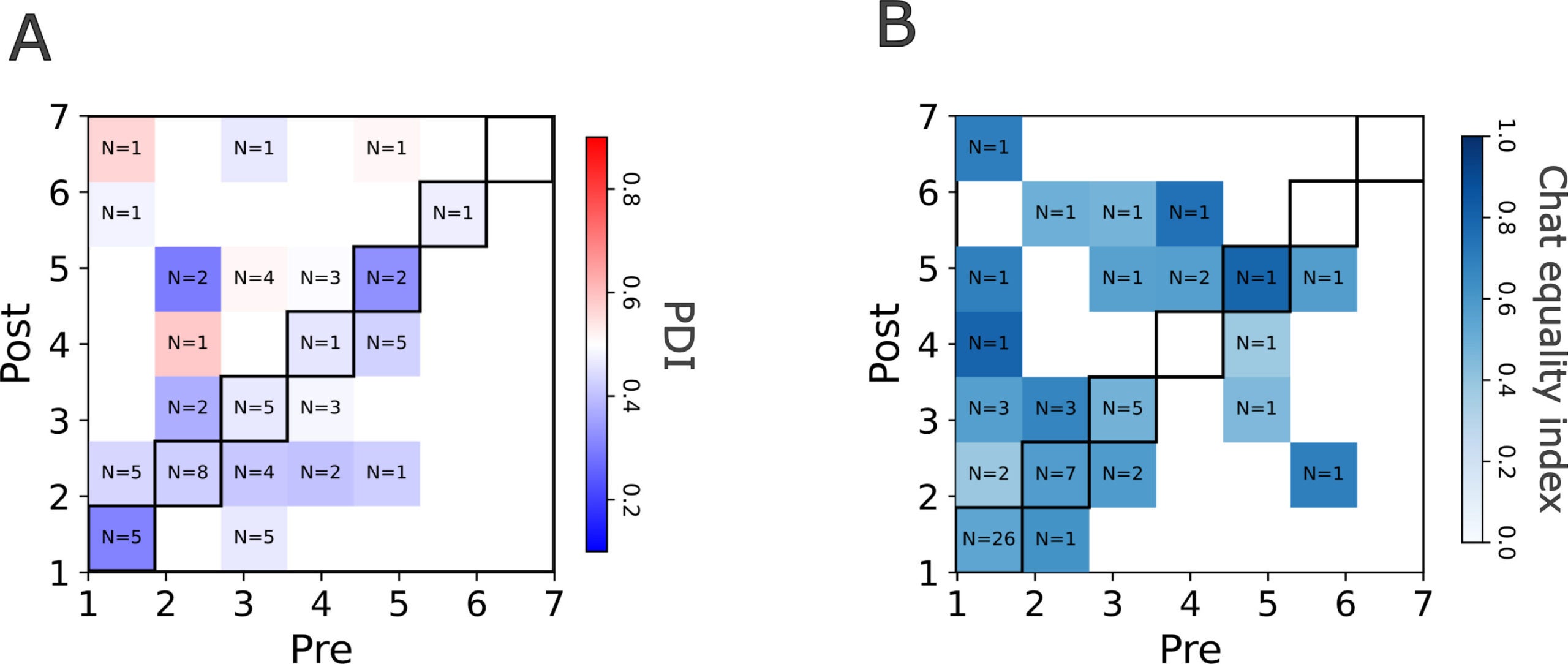

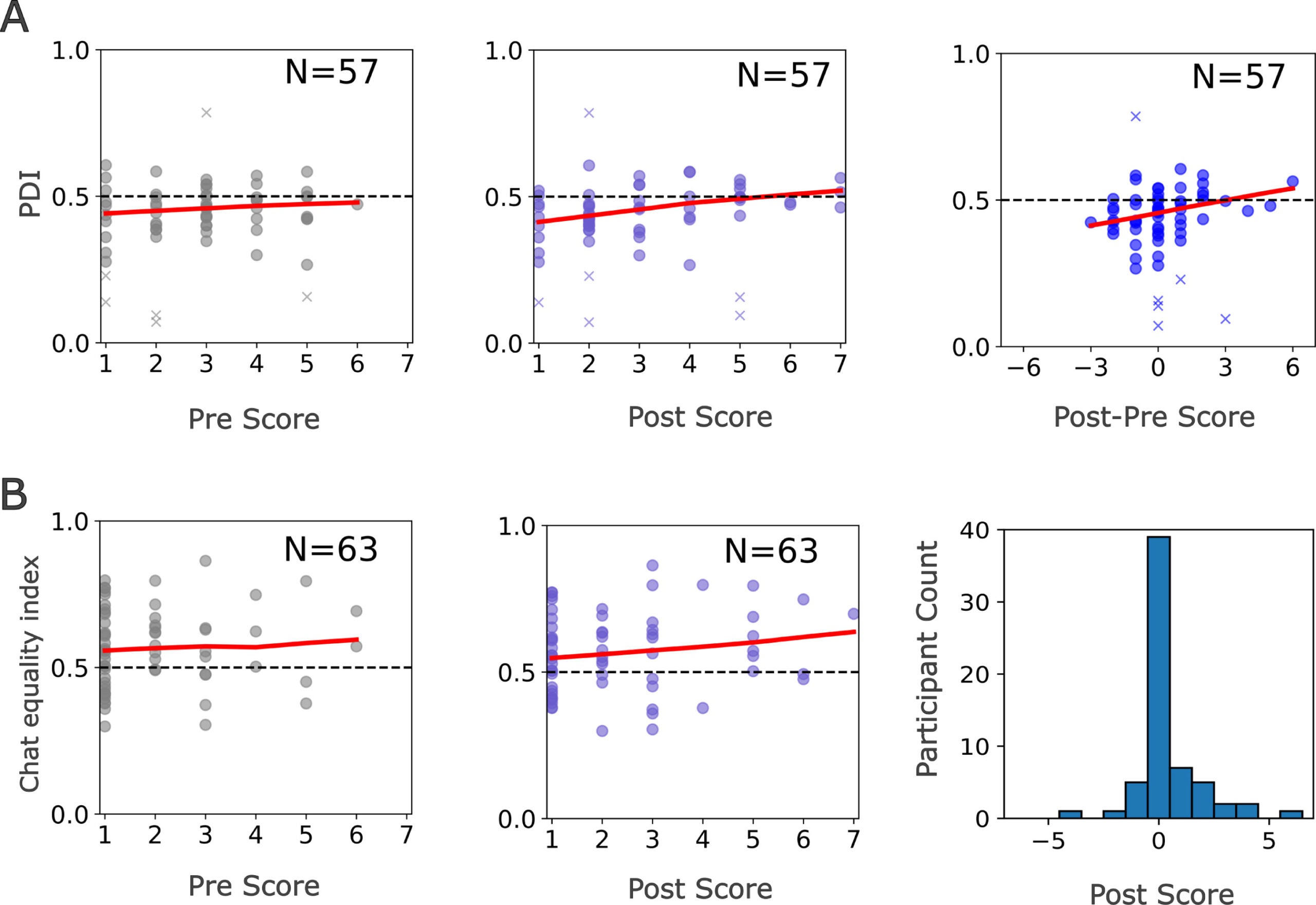

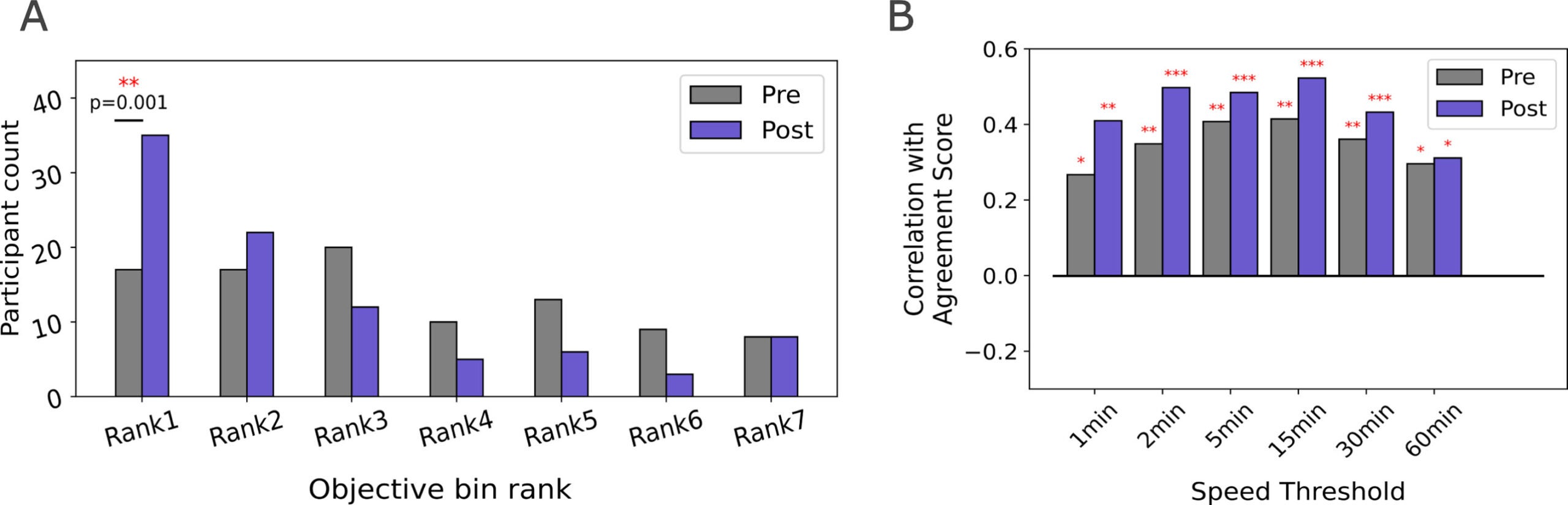

The results show a clear pattern. For two key areas, people became more accurate after seeing their data.

First, participants improved their sense of absolute response speed. Many had misjudged how quickly they usually reply. After viewing the charts, their estimates moved closer to the measured averages.

Second, they improved their sense of contribution share. In simple terms, they better understood whether they write more, less, or about the same as their partners. The visuals helped replace vague impressions with concrete proportions.

Not every belief changed. Some estimates were already close to reality. One example is response speed relative to partners. Many people already had a fair sense of whether they reply faster or slower than the other person in a chat. The feedback did not add much there.

Another stable area was peak activity time. People usually know whether they text more in the morning, afternoon, or evening. Seeing the charts did not move those beliefs much.

Two areas did change in feeling but not in accuracy. Participants adjusted their views about how evenly they spread messages across chats and how steadily they write throughout the day. Yet those new views did not align better with the data. This suggests some patterns remain hard to judge, even with feedback.

Small misunderstandings can strain relationships. A person who believes they always reply late may carry guilt or feel pressure that is not warranted. Another who thinks they dominate conversations may hold back when there is no need.

The study shows that these stories we tell ourselves often rest on shaky ground. Clear feedback can correct them. That matters because digital communication carries social meaning. Delays can feel like rejection. Long messages can feel like pressure. When people misread their own role, they can mismanage these signals.

The findings also show that people can handle honest feedback. The mood measures stayed stable. Participants did not become more anxious or less happy after seeing their charts. This result matters because it suggests that transparency does not have to hurt.

In practical terms, a person can learn that they are not as slow as they feared, or not as dominant as they assumed. That knowledge can bring relief and encourage healthier habits.

Memory is selective. It highlights unusual events and fades routine ones. A single ignored message can loom larger than dozens of timely replies. This bias explains why self-reports often miss the mark.

Data does not argue. It shows. A week of timestamps can reveal patterns that feelings hide. By turning those timestamps into simple visuals, the platform made behavior visible and easy to grasp.

This approach also avoids moral language. It does not label habits as good or bad. It presents facts. That tone likely explains why moods did not suffer.

The study adds to a growing idea in digital well-being. Tools that show people what they do can support better choices. The key is to present information in a way that feels supportive rather than accusatory.

Although the work focused on one app, the idea reaches further. Many parts of life now leave data traces. Email, social networks, calendars, and fitness apps all record behavior.

If people can see those patterns, they may understand themselves better. A clear view of work email timing could reduce stress. A simple chart of social media use could replace vague worry with facts.

The Bielefeld platform shows one way to do this while protecting privacy. It uses metadata, not content. It anonymizes records. It gives control to the participant.

The researchers suggest that such tools could support more mindful digital habits. Awareness often comes before change.

The study does not claim that feedback will change behavior. It focuses on understanding, not on intervention. It shows that beliefs can become more accurate. Whether that accuracy leads to different choices remains a question for future work.

It also does not claim that every aspect of self-perception can be fixed with charts. Some patterns, such as message distribution across chats, remained hard to judge. Human attention may still struggle with complex distributions.

Still, the work marks a shift from guesswork to evidence. It shows that even simple metrics can improve self-knowledge.

This study points to a practical path for digital well-being. Personalized, privacy-friendly feedback can help people replace anxiety and assumption with clear understanding. In everyday life, this can ease social tension, reduce unnecessary guilt, and support more confident communication.

For researchers, the work shows the value of moving beyond surveys toward behavioral data that respects privacy. Future studies can test whether similar feedback changes habits, improves relationships, or reduces stress. The same approach can extend to other platforms and daily activities.

For designers and policy-makers, the findings suggest that transparency tools do not need to shame or alarm. Calm, factual visuals can inform without harming mood. Over time, such tools could become a standard part of healthy digital environments.

Research findings are available online in the journal Computers in Human Behavior.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Why most people misjudge their texting, and how data can help appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.