Although yawning seems like a small, everyday action, recent studies have found that it causes an unexpected reaction in the fluid protecting the brain. A research team in Australia reports that a yawn pressurizes the cerebrospinal fluid away from the brain, and causes a reaction that is quite different than simply taking a deep breath into the lungs.

This research at the University of New South Wales, conducted with advanced MRI scanning technology, looked at how the brain migrates and moves during a yawn, as well as the amount of time it takes to migrate the CSF during the yawn. Adam Martinac, a neuroscientist at UNSW, and the researchers studied 22 healthy people and discovered some patterns that could explain the evolutionary pathway of yawning in many mammal species, including people.

Although there are still questions regarding why people yawn, scientists have discovered that yawning occurs in nearly all mammals, and most mammal species are capable of spreading the behaviour to one another. The UNSW team systematically studied the physiology of yawning, normal breathing, a deep breath, and suppression of yawns through scanning volunteers.

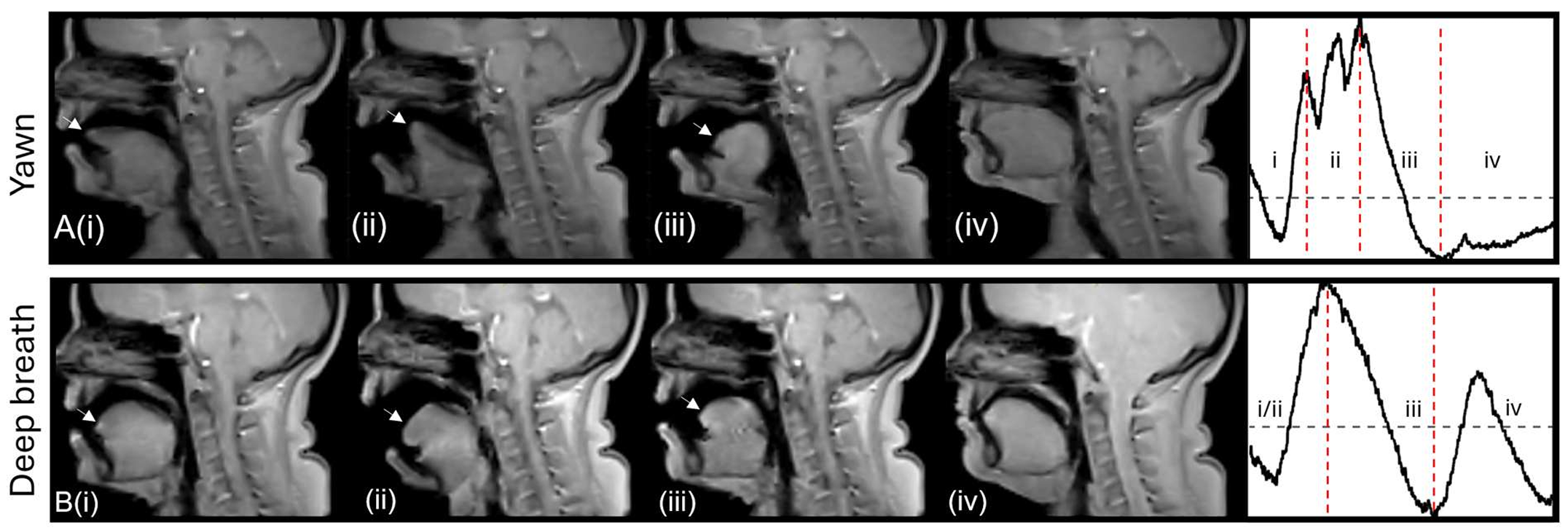

Initially, Martinac believed that yawning and deep breathing would have a similar physiological effect on the nervous system. However, the results showed differently.

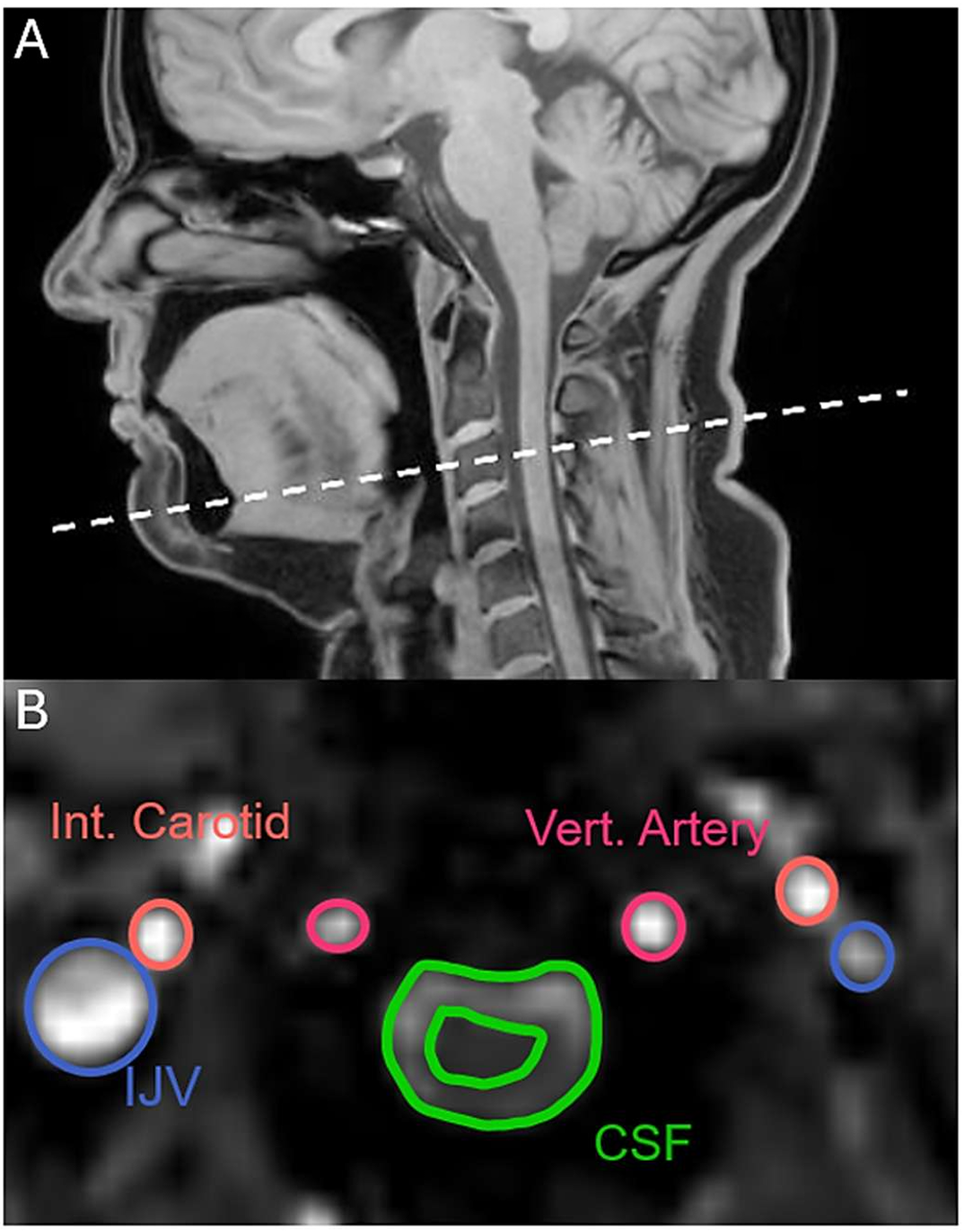

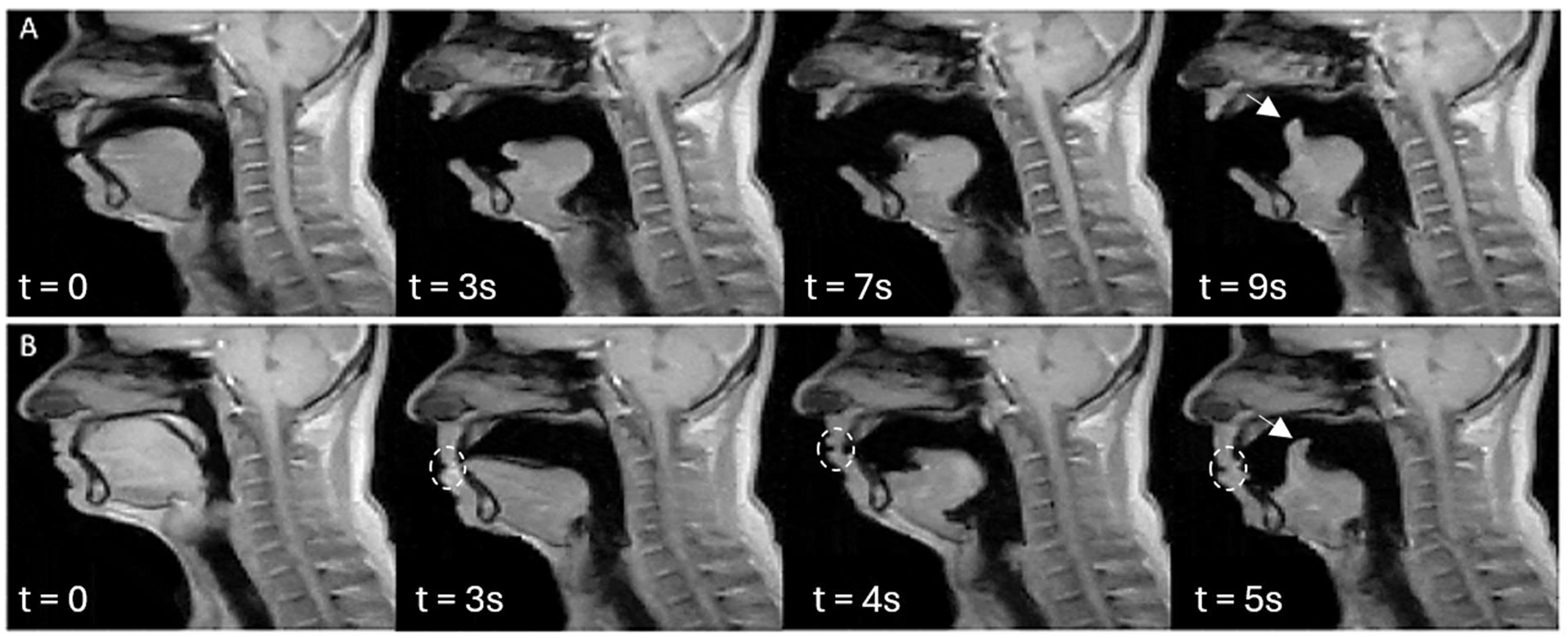

“The yawn seems to be creating a flow of CSF away from the brain, whereas taking a deep breath causes a flow of CSF towards the brain,” Martinac claimed. “This was an unexpected finding for us.” Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) surrounds and cushions the brain and spinal cord, as well as providing nutrients to the nervous system and assisting with the removal of waste. When someone takes a deep breath, their cerebrospinal fluid moves towards the brain. However, the fluid moves away from the brain while yawning.

The change in blood flow and pressure during yawning and taking a deep breath is also evident in the images. During yawning, there was an increase in blood flowing from the brain through the veins in the neck, creating space for fresh blood to enter the brain through the arteries.

Blood flow does not reverse direction when yawning, but during the initial phase of a yawn, the blood flow into the brain through the carotid arteries increases by 30%. Such an increase in blood flow into the brain during yawning indicates that yawning has a greater effect on circulation than just one factor.

The same pattern of cerebrospinal fluid movement and increased blood flow did not occur for every participant. The research team cautions that the differences seen between males and females may be attributable to the fact that males typically experience discomfort during magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning.

Finally, the research team noted that each participant had his or her own unique yawning style. Each person’s motion of his or her jaw and tongue was consistent each time he or she yawned. Even when the participant attempted to hold back the yawn, the same pattern of motion was observed. This suggests that yawning is controlled by inherent wiring in the brain rather than learned behaviour.

Research has shown that yawning patterns vary between individuals. However, each person tends to display a consistent yawning pattern over time. Yawning’s function is a mystery to many researchers, and they have put forth various hypotheses about why we yawn. The researchers have provided a new possibility that yawning may also be one method to move fluids around for optimal brain health.

CSF helps to clear toxins from brain tissues. Therefore, it is believed that yawning may remove some of the byproducts of neuronal activity from the brain. In addition, coordinated movement of blood and fluids may also help to maintain a constant temperature in the brain.

While the new findings do not definitively support either of these theories, they do demonstrate that the act of yawning has a definable and measurable effect within the body. Furthermore, they illustrate how closely tied yawning is to the central nervous system. The correlation between brain size and yawning time supports the findings of the present research regarding fluid flow.

Yawning is a well-known and generally understood act in society today, but we still do not completely understand the role it plays in the developing brain. The act of yawning, which we do frequently, occurs in many species, is very contagious among family members, and is closely interrelated with the brain’s internal processes.

The researchers noted that “Yawning is a significant adaptive behavior and further investigation into the physiological function of yawning will likely yield valuable insights on homeostasis of the central nervous system.”

The findings have not been published in a peer-reviewed journal. However, they present an opportunity to reexamine the significance of yawning in our daily lives. The next time a yawn takes you by surprise, consider the potential benefits it could have for your brain.

The findings of this study provide a clearer direction for future studies aimed at determining how movement of body fluids through the body could positively affect the brain’s overall health. If yawning indeed assists in controlling the flow of CSF, brain temperature, or both, such information may serve as the basis for future investigations related to sleep, fatigue, and neurological diseases.

Understanding how body fluids naturally cycle through the body during the act of yawning may be helpful in identifying new ways to investigate waste clearance processes in the brain.

As this behavior continues to develop, understanding yawning could assist in protecting the brain’s function as we age.

Research findings are available online in the journal bioRxiv.

The original story “Yawning may quietly protect your brain, study finds” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Yawning may quietly protect your brain, study finds appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.