You are taught early in science that oxygen on Earth comes from sunlight. Plants, algae, and cyanobacteria use light to split water and release oxygen, shaping the atmosphere and making complex life possible. That idea was shaken in July when marine ecologist Andrew Sweetman and colleagues at the Scottish Association for Marine Science published a study in Nature Geoscience. Working in partnership with international researchers, they reported something unexpected on the deep Pacific seafloor. Oxygen appeared to be forming in complete darkness.

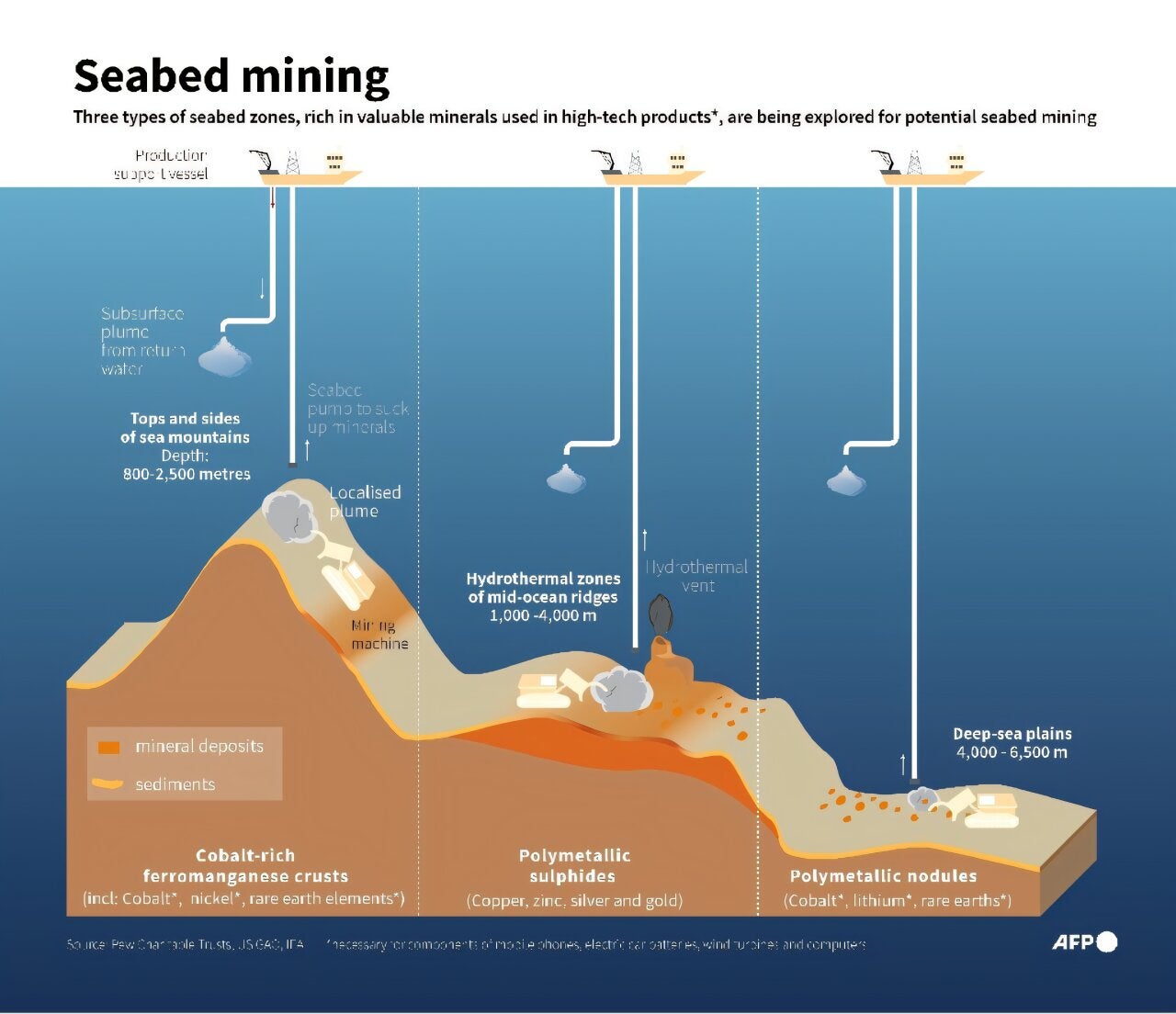

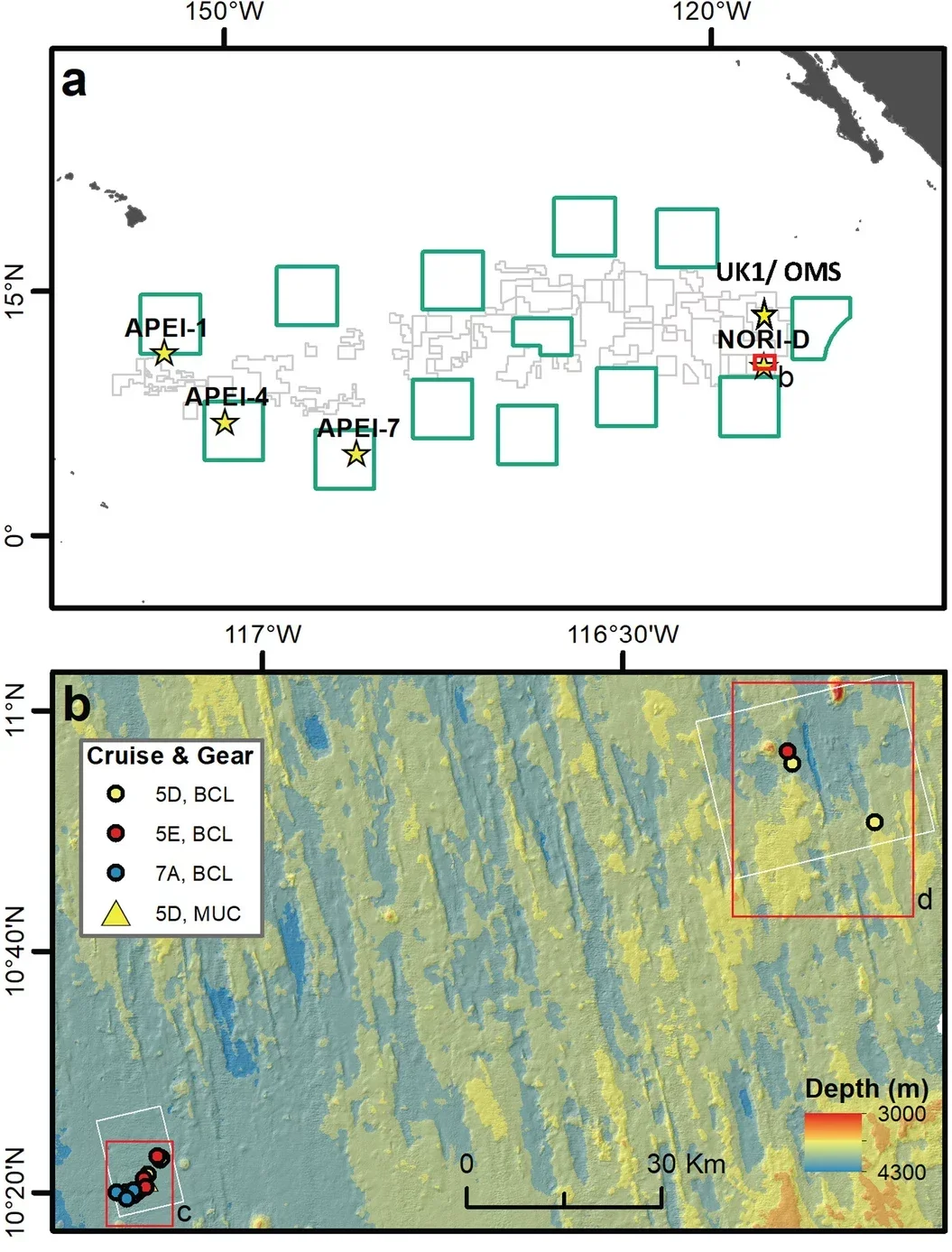

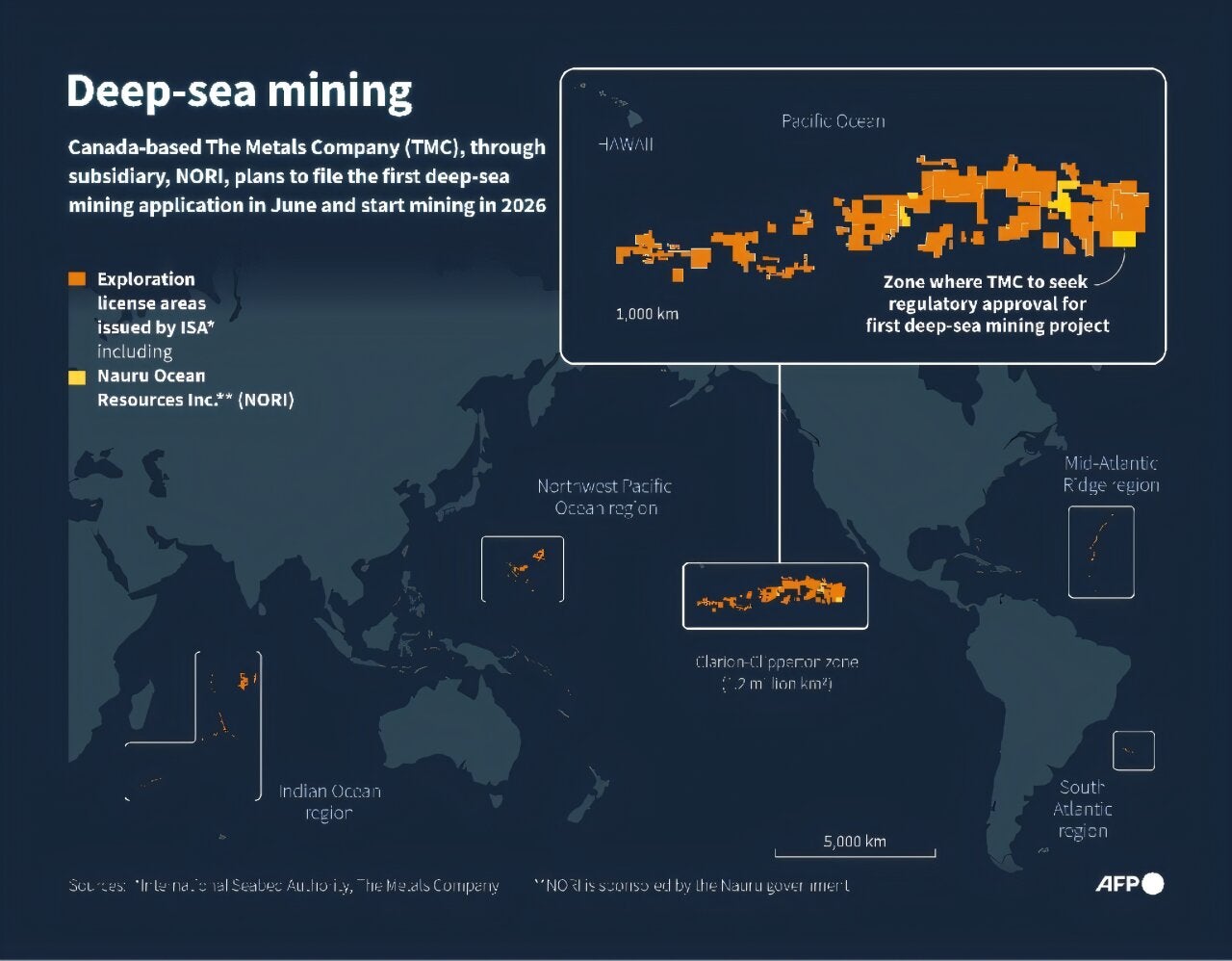

The work focused on the Clarion–Clipperton Zone, a vast region of the Pacific Ocean between Mexico and Hawaii. The area lies about four kilometers below the surface and is scattered with polymetallic nodules. These potato-sized metallic rocks are rich in manganese, nickel, and cobalt. The metals are valuable for electric vehicle batteries and other low-carbon technologies. They are also central to a growing debate over deep-sea mining.

Sweetman’s team reported that these nodules may be generating small electrical currents that split seawater into hydrogen and oxygen. The process is known as electrolysis. If confirmed, the finding would challenge long-standing ideas about how oxygen first appeared on Earth around 2.7 billion years ago.

“Deep-sea discovery calls into question the origins of life,” the Scottish Association for Marine Science said in a statement accompanying the research.

When you picture the deep seafloor, you likely imagine a quiet place where oxygen slowly fades away. That picture is usually accurate. Oxygen reaching deep sediments is typically consumed by microbes that breathe oxygen or by chemical reactions that break down reduced compounds. Together, these processes are called sediment community oxygen consumption, or SCOC.

SCOC measurements help scientists estimate how elements like carbon and nitrogen cycle through the ocean. They also set a clear expectation. Oxygen should decline in sealed chambers placed on the seabed.

That expectation shaped experiments carried out in the Nauru Ocean Resources Inc. license area of the Clarion–Clipperton Zone. Researchers lowered benthic chambers to the seafloor and monitored oxygen levels using sensitive sensors called optodes. Instead of falling, oxygen levels rose.

Across 25 experiments, oxygen increased regardless of treatment. Chambers received dead algae, dissolved carbon and ammonium, filtered seawater, or nothing at all. In every case, oxygen climbed. The pattern pointed to what the researchers called dark oxygen production.

Two experiments behaved as expected. Oxygen steadily dropped, and microprofiling showed SCOC values of about 0.7 millimoles of oxygen per square meter per day. Most chambers told a different story.

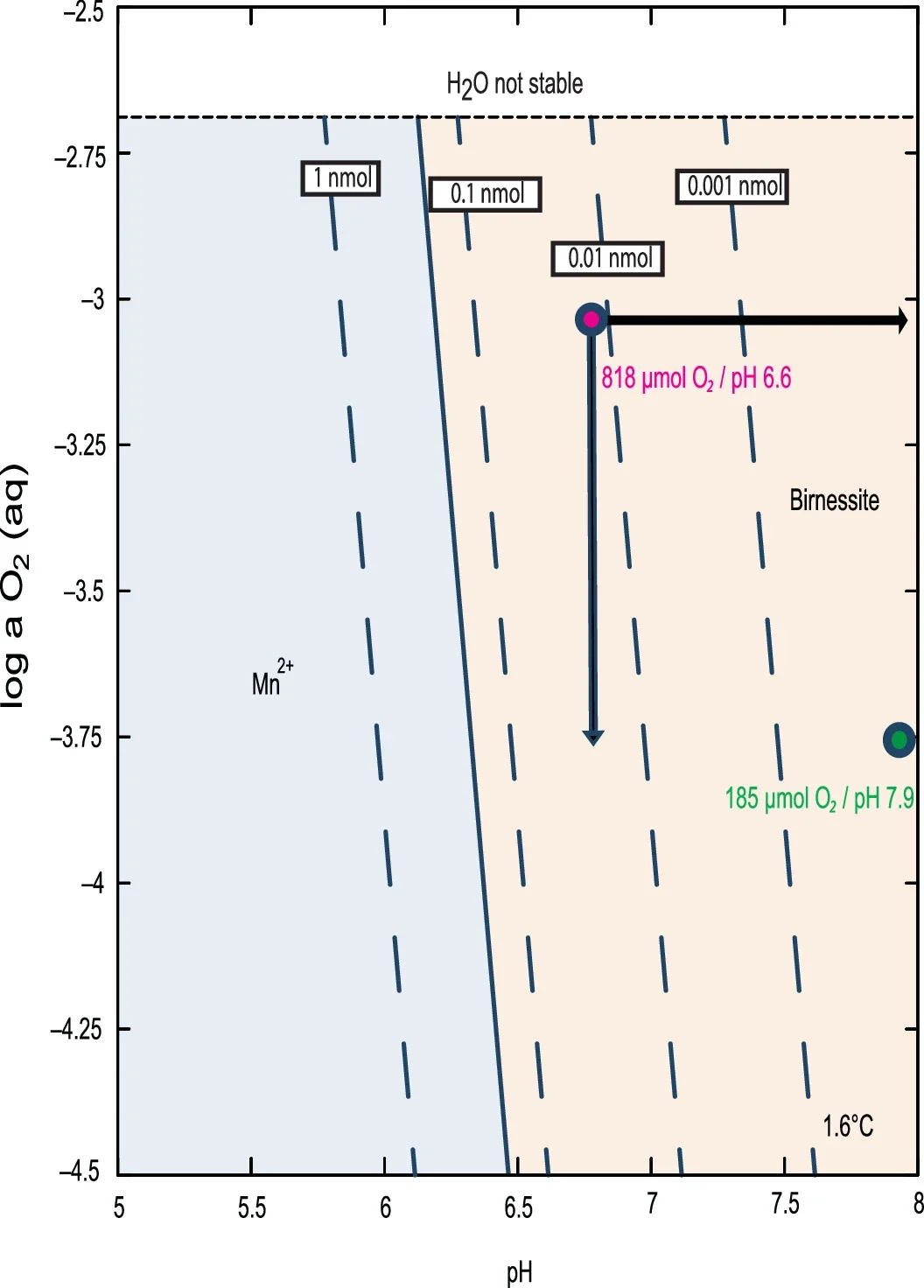

Oxygen concentrations started near 185 micromoles per liter. Within 47 hours, they climbed as high as 819 micromoles per liter. The resulting oxygen production rates ranged from 1.7 to 18 millimoles per square meter per day. These values far exceeded normal oxygen consumption.

To check the sensors, the team used Winkler titration, a standard chemical method for measuring oxygen. The results matched the optode readings. Statistical tests showed no meaningful difference between treatments or equipment types. Even older datasets from other cruises in the region showed the same trend.

One link stood out. Oxygen production increased with the surface area of nodules inside the chambers. Larger nodules were associated with more oxygen. That relationship suggested the nodules themselves mattered.

Before proposing new physics or chemistry, the team tried to rule out simpler explanations. Trapped air bubbles were unlikely. At depths of 4,000 meters, bubbles dissolve almost instantly. Leaks or contamination also failed to explain the results. All chambers were built from the same materials and followed identical procedures.

The researchers ran additional tests in sealed containers outside the ocean and again observed oxygen production. Pore-water measurements showed that sediment consumed oxygen rather than released it. These checks pointed away from equipment problems.

Biology was another candidate. Some microbes can produce oxygen through rare chemical pathways. To test this, researchers added mercury chloride, which kills many microbes and blocks known oxygen-producing reactions. Oxygen still appeared. The presence of oxygen in chambers containing only nodules further weakened a biological explanation.

The findings drew sharp criticism. Since July, at least five papers challenging the results have been submitted for review. Many scientists argue the evidence is incomplete.

“He did not present clear proof for his observations and hypothesis,” said Matthias Haeckel, a biogeochemist at the GEOMAR Helmholtz Center for Ocean Research in Kiel, Germany. “Many questions remain after the publication. So, now the scientific community needs to conduct similar experiments etc, and either prove or disprove it.”

Olivier Rouxel, a geochemist at Ifremer, France’s national ocean science institute, also expressed doubts. Deep-sea sampling is difficult, he said, and oxygen readings could reflect trapped air in instruments. He questioned how nodules tens of millions of years old could still generate electrical current.

“How is it possible to maintain the capacity to generate electrical current in a nodule that is itself extremely slow to form?” Rouxel asked.

Sweetman said the debate is expected. “These types of back and forth are very common with scientific articles and it moves the subject matter forward,” he told AFP.

“To explore how nodules might produce oxygen, our team measured electrical voltage across nodules collected from several parts of the Clarion–Clipperton Zone. Using platinum electrodes, we recorded voltages at more than 150 points,” Haeckel told The Brighter Side of News.

“Some readings reached 0.95 volts. While that is below the 1.23 volts normally required to split water, certain metal oxides can lower the energy needed. Polymetallic nodules contain layers rich in manganese, nickel, and copper. These metals can act as catalysts and improve conductivity,” he continued.

The researchers propose that nodules function as tiny electrochemical systems, sometimes described as geo-batteries. Internal electron movement between metal layers could drive partial electrolysis of seawater. Initial oxygen spikes may occur when nodules are exposed during lander placement. Production may then slow as reactive sites degrade.

If dark oxygen production occurs naturally, it could supply oxygen to deep-sea ecosystems in ways scientists never considered. The process may be uneven, depending on nodule size, density, and disturbance.

That uncertainty matters as interest in deep-sea mining grows. Environmental groups argue the discovery highlights how little is known about deep ecosystems. “This incredible discovery underlines the urgency of that call,” Greenpeace said, urging a halt to mining in the Pacific.

Mining companies disagree. The Metals Company, which partly funded the research, criticized the study. Michael Clarke, the company’s environmental manager, said the findings were “more logically attributable to poor scientific technique and shoddy science than a never before observed phenomenon.”

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Dark oxygen discovery in the deep ocean sparks debate over life’s origins appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.