That sharp flinch during a violent movie scene is familiar to many people. A hand slams, a body falls, and your own muscles tighten in response. The reaction feels instant and personal, even though nothing touched you. Scientists have long wondered why the brain responds this way.

New research now offers a powerful explanation. A study shows that when you watch someone being touched or hurt, your brain activates touch-related regions as if your own body were involved. Vision does not stay separate from feeling. Instead, the brain blends the two through detailed internal body maps.

The work was led by scientists from the University of Reading, the Free University Amsterdam, and research partners in Minnesota. Their findings suggest the human brain does not simply observe the world. It quietly simulates it.

“When you watch someone being tickled or getting hurt, areas of the brain that process touch light up in patterns that match the body part involved,” said Dr Nicholas Hedger, lead author from the Centre for Integrative Neuroscience and Neurodynamics at the University of Reading. “Your brain maps what you see onto your own body, simulating a touch sensation even though nothing physical happened to you.”

For decades, scientists believed the brain handled vision and touch in mostly separate systems. Visual areas processed images. Touch areas handled physical sensation. This study challenges that idea.

Using advanced brain imaging, researchers examined activity in 174 people while they watched full-length films, including The Social Network and Inception. These were not short clips or simple images. They were rich scenes filled with motion, emotion, and human interaction.

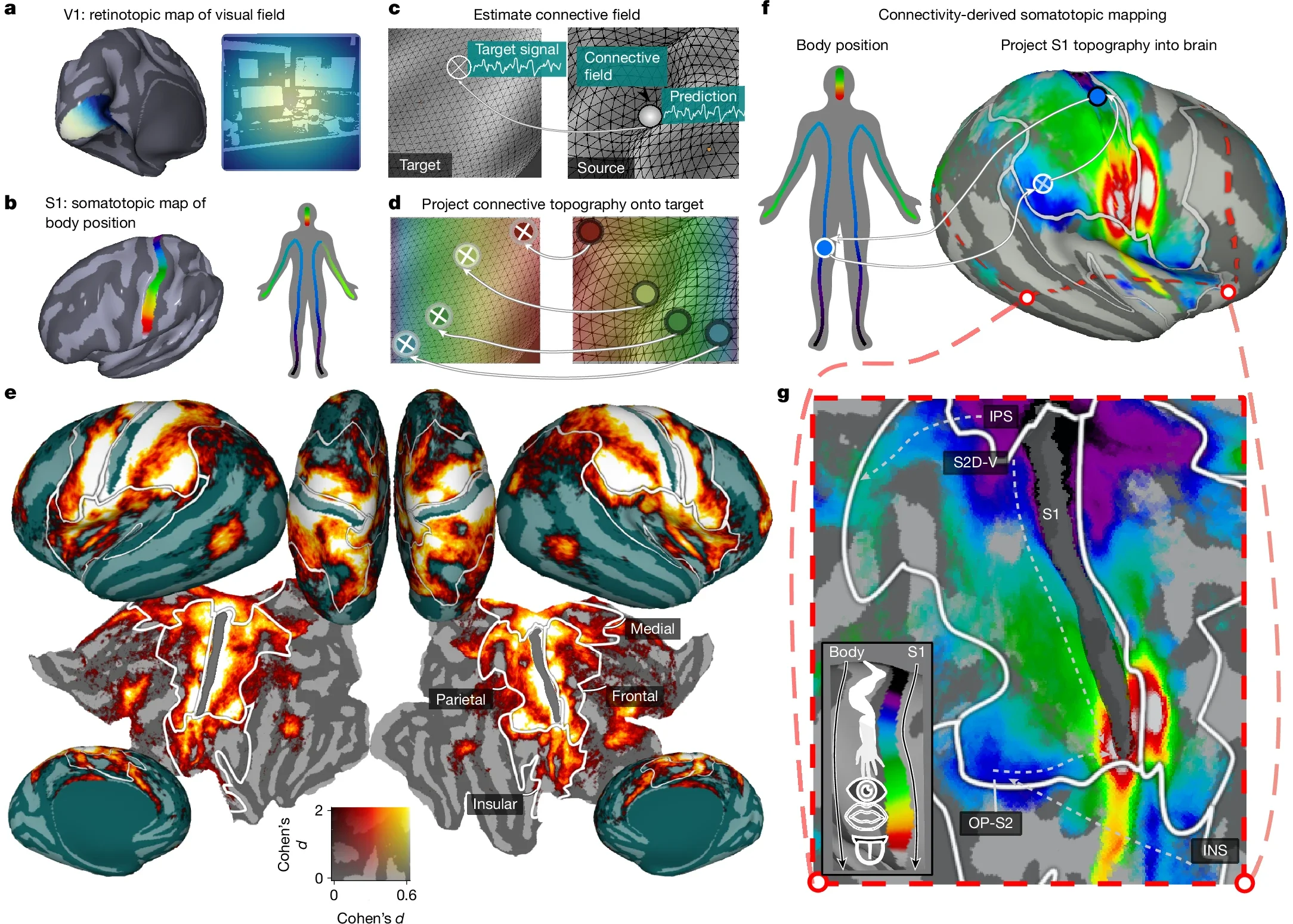

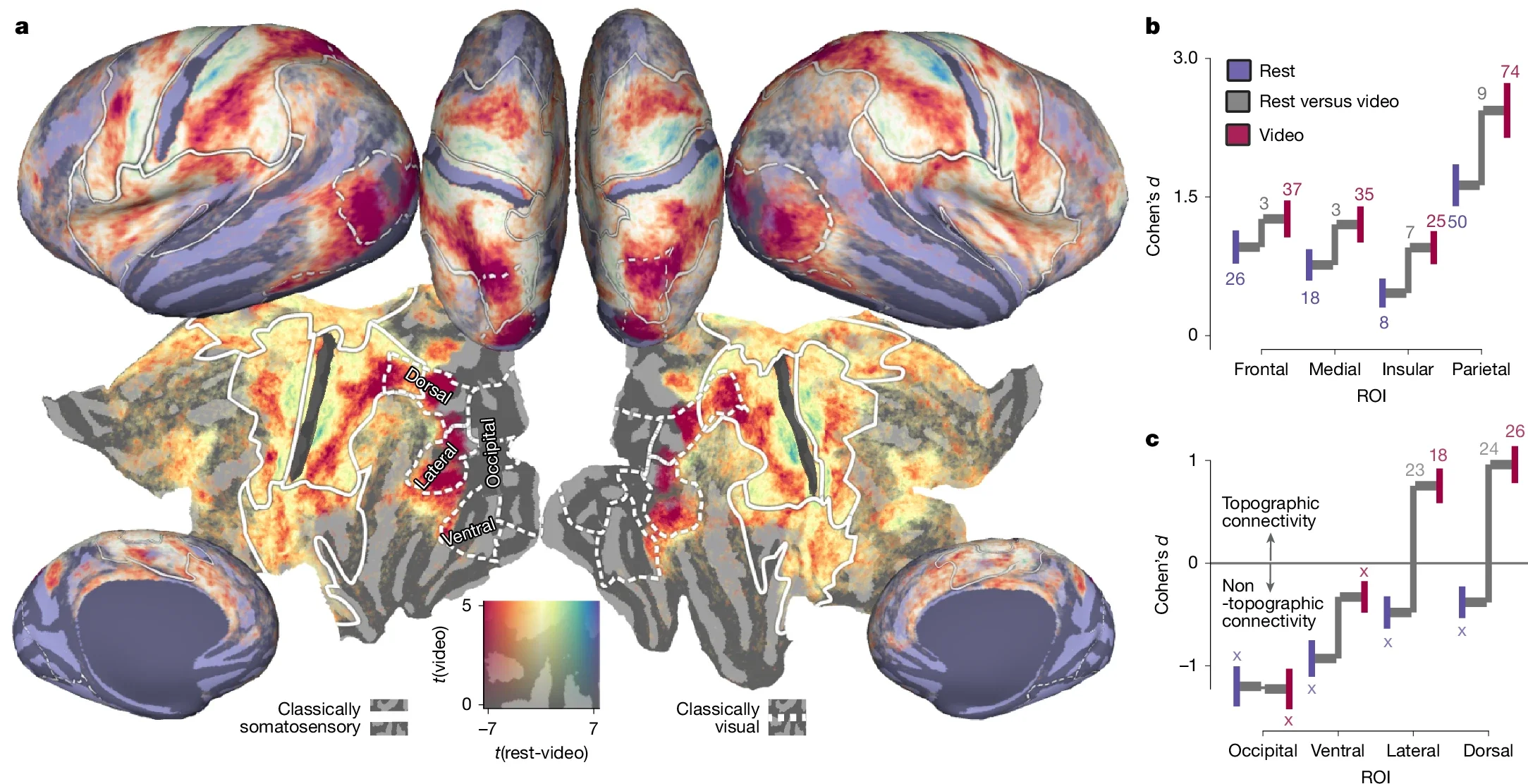

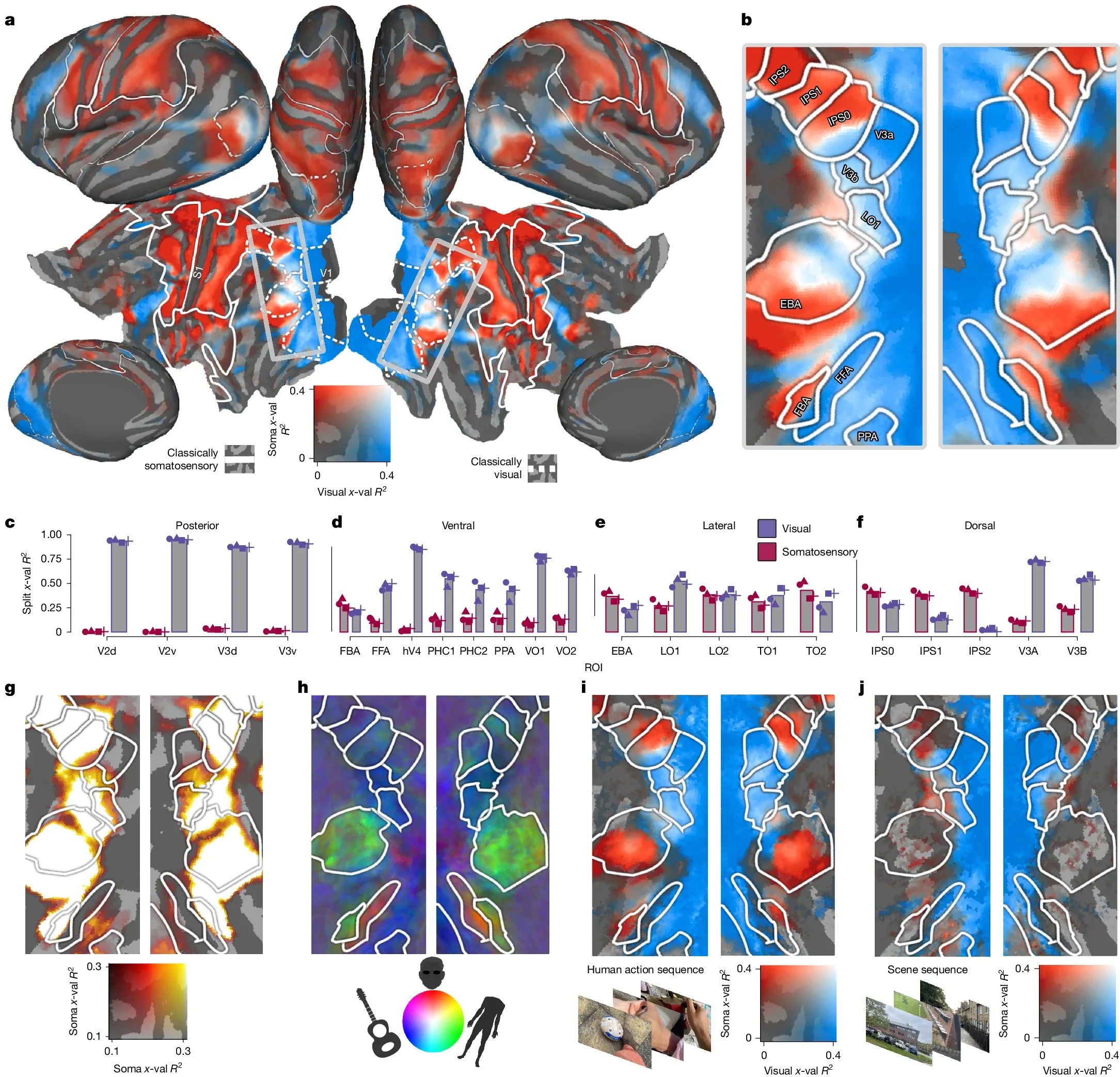

While participants watched the movies, researchers tracked patterns across the brain. What they found surprised them. Regions long thought to process only visual information also showed organized patterns tied to the body. These areas reflected which body part appeared on screen, such as a hand, face, or foot. Even more striking, the patterns matched how the brain normally organizes physical touch.

In effect, parts of the visual system contained hidden body maps. The same neural layout used to feel touch was also being used to interpret what was seen. “The machinery the brain uses to process touch is baked into the visual system,” Hedger said.

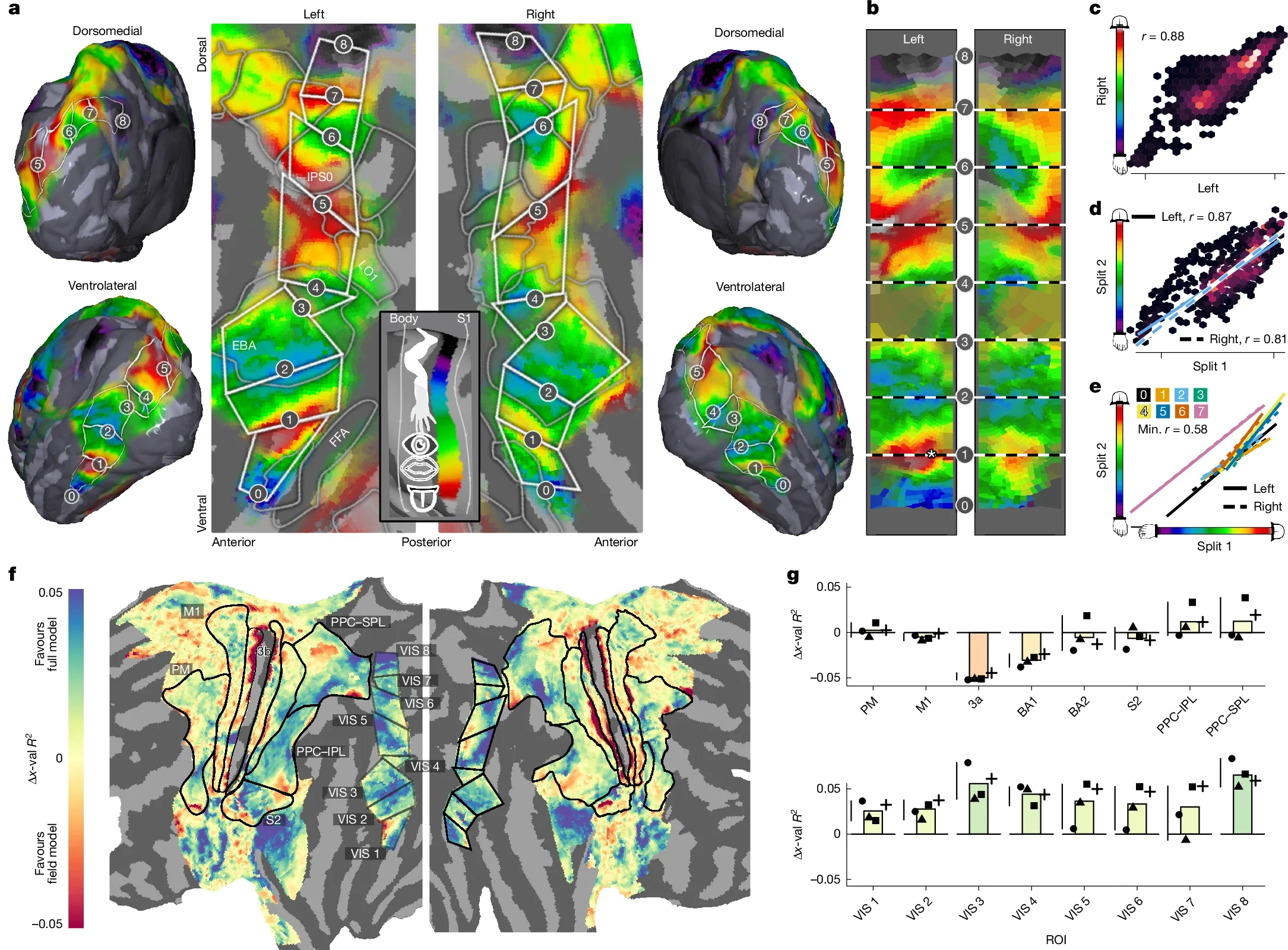

To understand how this works, researchers looked closely at how different areas of the visual system responded. They found two main patterns. In upper regions of the visual system, body maps aligned with visual space. Areas linked to feet matched lower parts of the screen. Areas linked to the face matched higher visual space. This meant the brain connected where something appeared with how that body part is represented internally.

In lower regions of the visual system, the mapping worked differently. These areas focused on what body part was being seen, regardless of where it appeared on the screen. A hand triggered hand-related brain patterns even if it appeared off to the side. Together, these two systems create a powerful link between vision and the body.

What you see becomes organized through the same framework your brain uses to feel yourself. The result is a shared internal map that ties sight directly to physical experience.

This discovery helps explain a common human reaction. When someone on screen gets hurt, the brain does not remain distant. It briefly mirrors the event through its own sensory layout.

That does not mean pain is fully felt. But the brain runs a partial simulation. This internal echo may be why people wince, tense, or pull back during intense scenes. The reaction happens before thought. It rises from deeply wired systems designed to connect perception with the body. These simulations also appear to support empathy.

Seeing another person’s experience activates patterns related to your own physical self. This may help the brain understand others more quickly and emotionally. Rather than thinking about what someone feels, the brain partially maps it. This process may help explain why human social understanding feels instinctive rather than calculated.

The connection between senses does not move in only one direction. Dr Hedger noted that touch also supports vision. “When you navigate to the bathroom in the dark, touch sensations help your visual system create an internal map of where things are, even with minimal visual input,” he said. “This filling in reflects our different senses cooperating to generate a coherent picture of the world.”

In low light, your brain blends memory, movement, and touch to guide you. Vision becomes supported by body awareness. The study shows that this cooperation is not occasional. It is built into the brain’s structure. Vision and touch are partners from the start.

The research team developed new analytical tools to study natural brain activity during real viewing experiences. Instead of testing isolated tasks, they observed how the brain behaves during everyday visual input. This approach allowed them to detect subtle patterns that traditional experiments often miss.

By watching full films, participants engaged emotional, social, and sensory systems all at once. That complexity helped reveal how the brain truly processes real life. The findings suggest that the brain’s organization is far more integrated than once believed. Sensory systems overlap, cooperate, and share internal maps.

This view changes how scientists understand perception itself. The brain does not build reality from separate parts. It blends them into a single experience.

Researchers believe this discovery could help advance understanding of autism and other conditions that involve sensory processing differences. Many theories suggest that internally simulating what we see helps people understand others. If those simulations function differently, social perception may also differ. Traditional sensory tests can be tiring and stressful, especially for children or people with neurological conditions.

This research offers a gentler approach. “We can now measure these brain mechanisms while someone simply watches a film,” Hedger said. That opens new possibilities for studying sensory integration without requiring difficult tasks or direct physical testing. It may also help scientists explore how perception develops and how sensory systems interact across the lifespan.

The study offers a deeper view of what it means to perceive the world. Seeing is not passive. Watching is not distant. Each image passes through a brain that understands the world through the body.

When someone moves, touches, or reacts on screen, your brain quietly translates that sight into bodily meaning. That translation may help you connect, understand, and respond. The findings show that human perception is not just visual. It is embodied. What you see becomes something you almost feel.

This research improves understanding of how the brain blends senses to create perception. It may guide new approaches for studying autism and sensory processing differences.

The ability to measure sensory integration during simple movie viewing could reduce stress in clinical testing.

The findings may also influence future brain-based technologies that aim to model human perception more naturally.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post New brain study reveals why watching pain on screen can feel real appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.