Every year, thousands of discarded artificial satellites are orbiting the planet, with an increasing number falling back into Earth’s atmosphere. Most of these objects will be destroyed before they hit the ground. However, some will survive long enough to pose a danger to the environment and people in the vicinity. Researchers from Johns Hopkins University and the University of London are now reporting a method by which we can track these falling satellites using existing seismic monitoring networks that are already used for detecting seismic activity and earthquakes.

The investigation was led by Benjamin Fernando, who is a postdoctoral fellow at Johns Hopkins University, studying seismic activity on both Earth and other planets, with co-author Constantinos Charalambous, who is a research fellow at the University of London. Their findings have been published in the journal Science, showing that there are ways to track space debris using seismic data to identify where space debris is going and where space debris may land soon after re-entering Earth’s atmosphere.

“There are an increasing number of re-entries occurring daily,” says Fernando. “In 2010, there were numerous satellites re-entering the atmosphere every day, and we had no way to verify independently where they re-entered, whether they broke into pieces, if they burned up in the atmosphere, or whether they landed on Earth. This issue is growing and will only grow further.”

When falling objects re-enter Earth’s atmosphere at high speed, they generate sonic booms. These sonic booms create shockwaves that ripple away from the object and through the ground beneath. While regular seismic sensors are used to detect and measure earthquakes, the same techniques can detect the seismic energy created when an object re-enters.

Researchers map the seismometer signals to track an object through space, including detailed information about its speed and direction, as well as its altitude. By analyzing these signals from multiple locations and different times of recording, patterns emerge showing how long the object remained at each altitude, including the time of fragmentation.

“We used the same methodology to analyze the April 2, 2024, reentry of China’s Shenzhou-15 orbital module. This module, measuring approximately 3.5 feet in diameter, weighed over 1.5 tons. This would make it dangerous if any component reached the Earth’s surface,” Fernando told The Brighter Side of News.

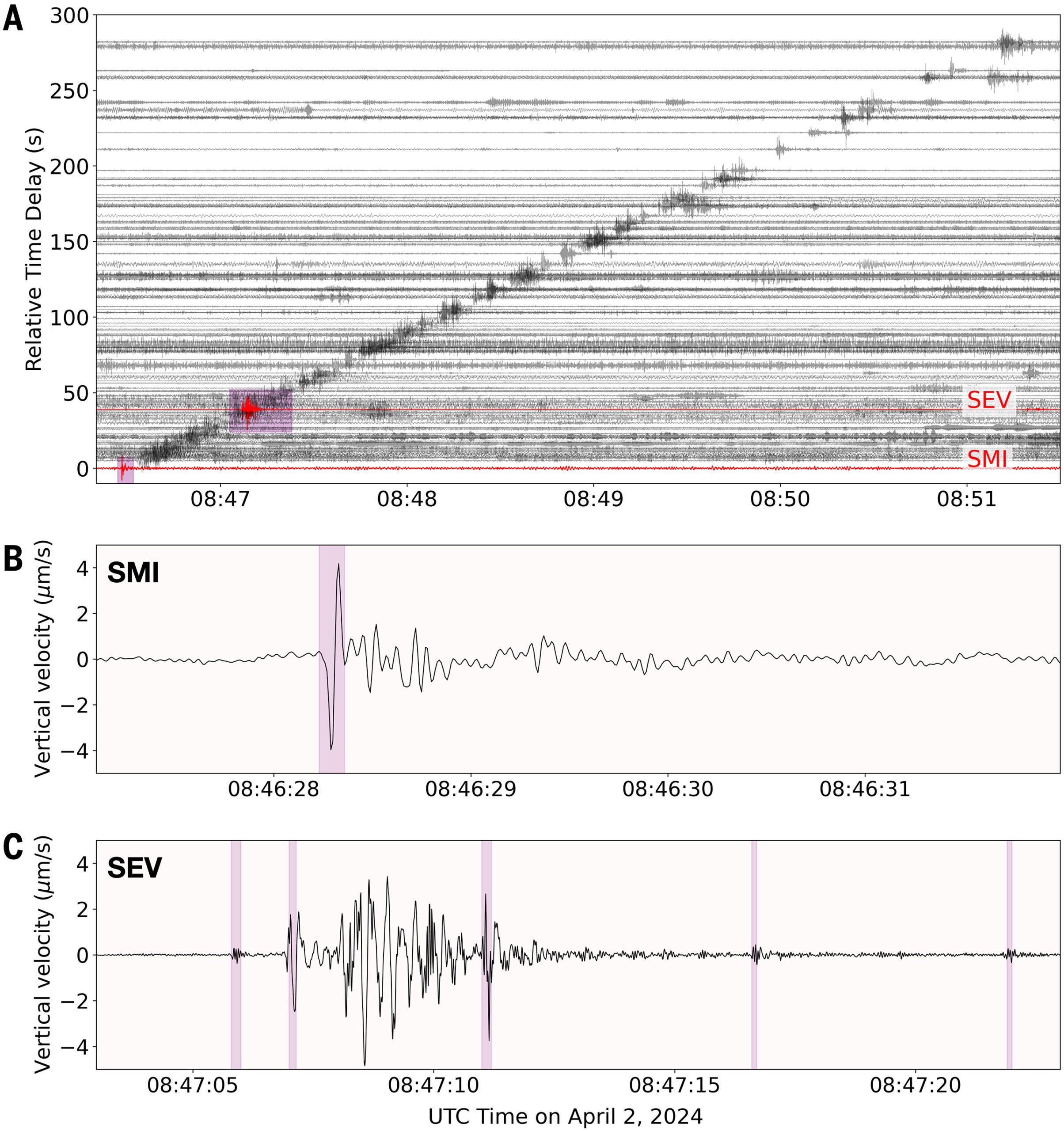

The seismometers selected for this study were located in Southern California. When the module entered the atmosphere and reached hypersonic velocities, all 127 of these seismometers showed evidence of multiple sharp vibrational tracks.

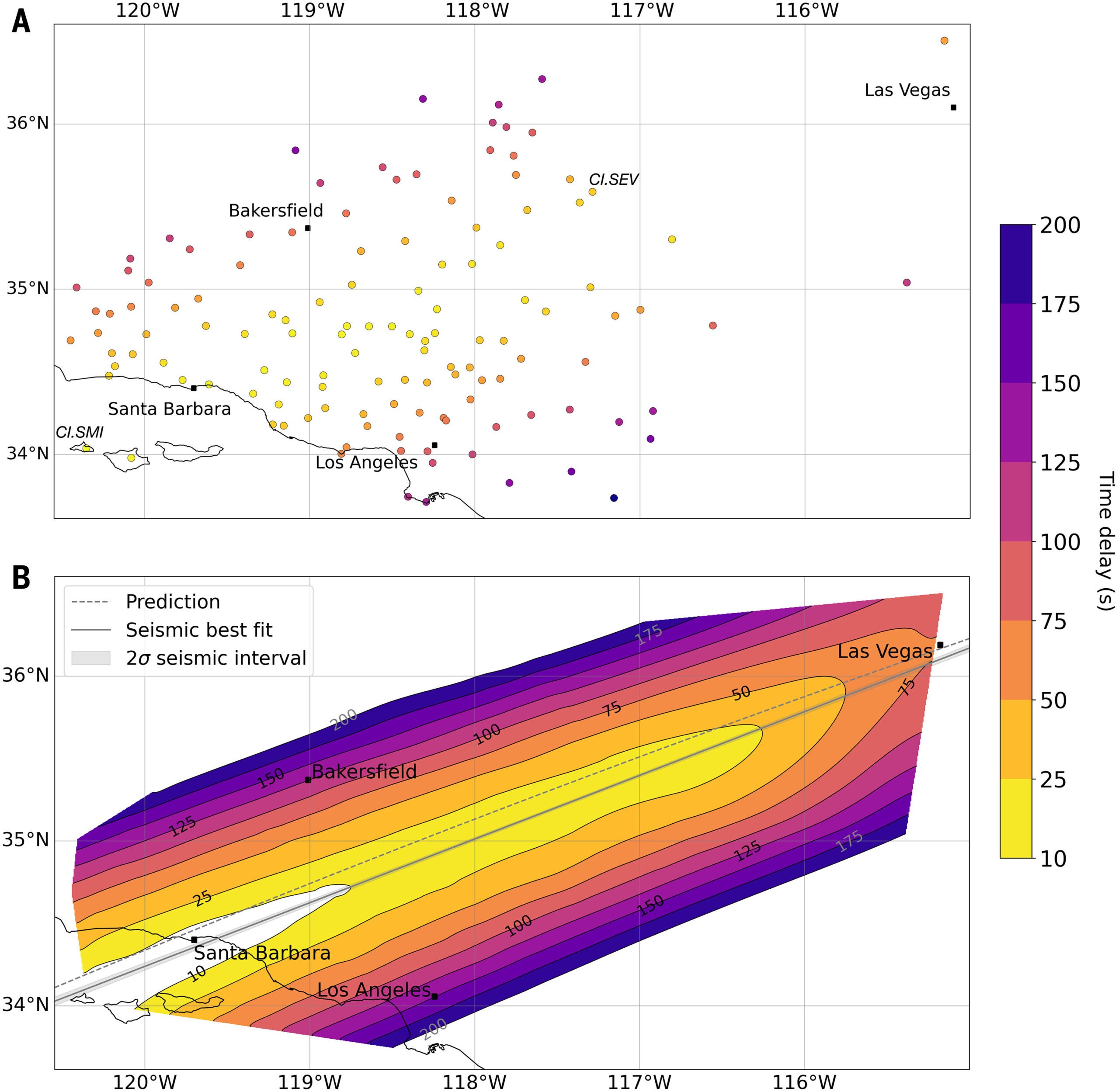

From the seismometer data, they determined that the object had followed a northeasterly path and passed over both Santa Barbara and Las Vegas. It was traveling at speeds estimated between Mach 25 and Mach 30, or roughly ten times faster than the world’s fastest jet. Based upon the timing and intensity of these vibrational signals, they reconstructed the object’s trajectory and used this information to determine when fragmentation began.

The team’s reconstructions placed the flight path approximately 25 miles north of the predicted reentry path computed by United States Space Command based on orbital tracking data alone. This illustrates the high level of uncertainty inherent in making predictions based solely upon orbital tracking once an object passes through areas of greater atmospheric density.

Scientists currently use radar and optical technologies to determine where an object will land based on the object’s trajectory prior to re-entry. However, these systems work effectively in orbit but lose effectiveness due to atmospheric drag as objects descend through the upper and lower atmosphere. Thus, in certain instances, estimates can be thousands of miles off at the time of atmospheric re-admittance.

Once the object reaches the thermosphere region, it will experience erratic movement due to atmospheric heating, decreases in air density, and structural failures. This makes many of the present-day means of tracking objects at these altitudes extremely difficult to predict using optical devices. In addition, many radar tracking records remain restricted to classified military purposes.

As a result of inconsistencies in both tracking systems, the object remains out of reliable tracking until shortly before it enters the upper atmosphere. At this point, it begins to segregate into smaller pieces and ultimately falls out of reliable tracking. This creates large uncertainty gaps. The consequences of incidents such as debris from spacecraft falling in Caribbean waters and the breakup of the radioactive Soviet satellite Kosmos-954 clearly illustrate the high degree of risk associated with these types of events.

The seismic data of Shenzhou-15 not only reflected its trajectory, but the initial reflections also provided evidence that the spacecraft was mostly intact at the time of its high-altitude trajectory. When examining the later data, however, many of these signals indicated complex waveforms and numerous waveforms within close proximity to one another. This unique pattern indicated fragmentation, which occurred as many of the smaller pieces created their own sonic booms.

The analysis indicated that the spacecraft likely separated through a cascading process and not a single explosive event. Specifically, researchers documented a total of eight to eleven unique breakup events within a time frame of approximately two seconds. Based on the aforementioned events, it was evident that progressive structural failures contributed to the release of lower amounts of energy compared to previous re-entries.

The gradual degradation pattern emphasized that there were likely dense and reinforced components still intact long enough to escape into the upper atmosphere after re-entry. This ultimately increased their chances of survival.

Falling debris poses a threat beyond just where it lands. Spacecraft that disintegrate during re-entry will produce tiny particulate matter that becomes part of the atmospheric system and is transported by weather systems. Many spacecraft contain toxic propellants and or radioactive materials.

Fernando indicated that a Russian spacecraft, Mars 96, disintegrated in December of 1996. At the time, there were speculations that it had completely burned up upon re-entry, but that its radioactive power source landed intact in an ocean. Tracking the source of this debris was difficult, and its final location was not confirmed.

A group of Chilean scientists later found man-made plutonium in a glacier in Chile. They suspect it was from the radioactive power source of Mars 96 and believe it was ejected during the disintegration of Mars 96 as it passed through the atmosphere, likely contaminating the area. It would be beneficial to have better ways to track items, especially when they contain radioactive materials.

Near real-time location services for tracking objects descending onto Earth would assist authorities in reducing response time to the landing of space debris. By providing accurate information on a specific location of a spacecraft in the upper atmospheric region in minutes instead of days or weeks, authorities could develop recovery methods much quicker. This would help protect people and aid in the identification of hazardous materials.

In addition to using this information to recover radioactive debris, accurate location data could also be used to provide aircraft warnings and environmental monitoring. This approach provides researchers with an additional technique for studying spacecraft failure modes during atmospheric re-entry. It also allows them to improve safety-related aspects of spacecraft design and develop better means of disposing of debris created during re-entry.

As the number of launches increases and more large satellite constellations reach the end of their design lives, tools such as near real-time location services will become increasingly important. These tools will help manage the risk associated with uncontrolled atmospheric re-entries of space debris.

“It matters if you can figure out where it landed within 100 seconds versus determining where it landed in 100 days,” Fernando said. “We need as many different ways as possible to track and characterize space debris.”

Research findings are available online in the journal Science.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Scientists turn earthquake sensors into dangerous space debris trackers appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.