The more camouflage Harris-Walz trucker hats I saw around Brooklyn, the greater my sense of foreboding. “Courting disaster,” I texted a colleague, half-joking, as I walked to my Fort Greene polling site on Election Day. Scanning as working class, the hats seemed to be worn exclusively by people who didn’t match that description. They reminded me of the Big Buck Hunter arcade game at a bar near the campus of my elite college, which lent wry “authenticity” to the setting and whose plastic rifles were the only kind most of us had any interest in handling. I wondered if some of the hat wearers were in on the joke or simply liked the aesthetic. But some of these people looked sincere, as though they felt the hats really reflected the campaign’s resonance with regular folks.

In the end, the Harris campaign lacked such appeal. Blue-collar voters of every ethnicity drifted right. Donald Trump, according to exit polls, carried voters from families earning between $30,000 and $50,000, a group Joe Biden had won by 13 points. Among minorities without a college degree, Harris performed 26 points worse than Clinton did in 2016. Trump’s 45 percent share of the Latino vote was the highest ever for a Republican presidential candidate. Cementing her party’s new white-collar identity, it was Harris this time who won voters making six figures or more. Never in the recent history of the Democratic Party has a presidential campaign appealed less to the actual trucker-hat set, auguring a tectonic class realignment of the two parties.

Denial has been a trademark Democratic reaction in the Trump era, beginning with the protective response to his first victory. Many shocked or grieving voters in 2016 found reasons to regard the result as a fluke rather than accept the fact of Trump’s surprising popularity. Among the explanations they supplied: damaging WikiLeaks dumps of hacked Democratic emails, James Comey’s “October surprise” letter to Congress about Hillary Clinton’s personal email server, and the media’s skewed coverage of these events. Others blamed Jill Stein for peeling off voters in the Midwest, while Russian election interference both explained voters’ incomprehensible support for Trump — i.e., perhaps the Russians tricked them with disinformation — and provided a justification for reversing the result altogether. Especially because Trump lost the popular vote, one could fashion an alternate reality in which he was not the legitimate victor, captured by the slogan “Not My President.”

If Trump’s victory was not in fact a reflection of voter sentiment, it became less important to court or win back his voters. Through the resistance years and into the COVID era, liberal institutions from universities to media organizations to nonprofits cathartically swung left, which bred further denial about what voters cared about and were experiencing. A partial catalogue of progressive denialism, listed in no particular order: that alienating progressive positions or rhetoric were confined to college campuses; that the externalities of pandemic shutdowns, such as grade-school learning loss, were overblown; that the rapid adoption of new gender orthodoxies, especially in settings involving children, was not a popular concern; that the “defund the police” movement would be embraced by communities of color; that inflation was overstated; that the pandemic crime wave was exaggerated; that concerns over urban disorder represented a moral panic; that Latinos would welcome loosened border restrictions. Thanks to these and other issues, the gap continued to widen not just between liberals and conservatives but between the highly educated elite and the moderate rank and file of the Democratic Party.

Cracks in the party’s Obama-era multi-racial coalition had been showing for several years, as the party shed minority voters in 2020 and 2022 despite good results overall. Yet the Harris campaign backed away from populist overtures and instead tried to run up the margins among voters already horrified by Trump or galvanized by the Supreme Court’s reversal of Roe v. Wade. Shortly before the election, my colleague Gabriel Debenedetti quizzed top Harris strategist David Plouffe on Trump’s growing popularity with Black and Latino men. Plouffe answered blithely, “The bigger issue here is Donald Trump’s huge struggle with women voters, college-educated voters, suburban voters.”

The election, which saw Trump win the popular vote outright, blindsided Democrats and many in the partisan media. “These results were a surprise to everyone,” wrote Heather Cox Richardson, a Boston College historian and wildly popular Substack author. The greatest surprise of all was Trump’s popularity in supposedly blue America, from New Jersey to the Texas border. And it appears no state in the country shifted more toward Trump than New York and no metropolis more than New York City. On the Wednesday after the election, many New Yorkers woke up feeling like strangers in their own land. HARRIS-WALZ, OBVIOUSLY read the lawn signs, but now the consensus seemed muddled. That day, the New Yorker writer Emily Nussbaum posted a message to the liberal social network Bluesky lamenting her choice to visit a diner in brownstone Brooklyn, which she found “full of buoyant MAGAs, including an old guy in a MAKE AMERICA GREAT BRITAIN AGAIN hat, babbling about migrants and Hillary, and a woman in a MAKE AMERICA NORMAL pro-Haley T-shirt. In South Slope!”

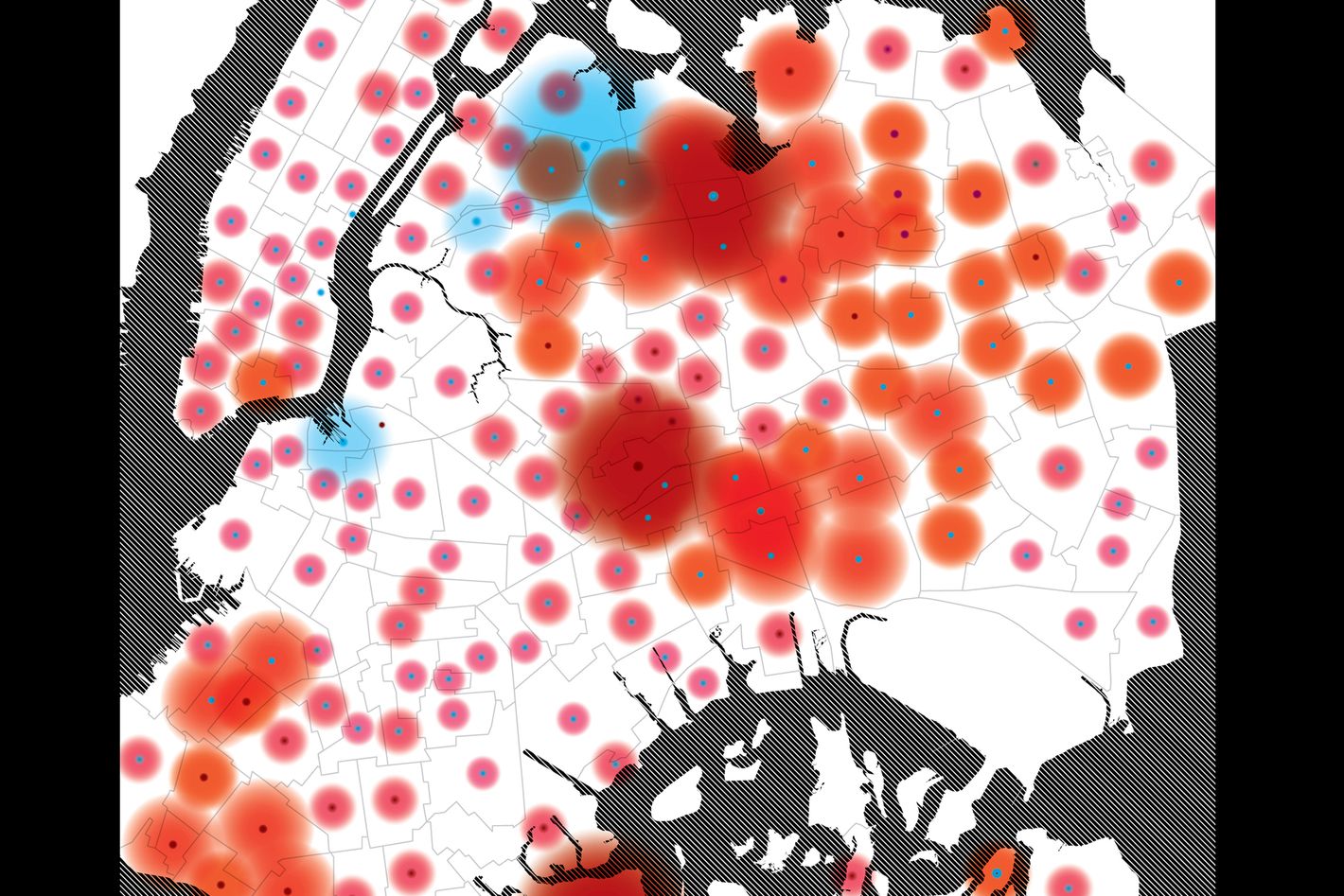

In truth, the MAGA faithful are not among the city’s upper-middle-class liberals in any meaningful way. Neighborhoods like Park Slope are some of the only ones in the city that remained dark blue this cycle. It was instead the areas of the city where some of the least wealthy and least white reside that broke hardest toward Trump. These neighborhoods, and the reasons they voted as they did, have been out of the field of vision of many of the very people, here in the country’s media capital, who have tasked themselves with reporting on, understanding, and explaining American politics. This myopia reflects a Democratic Party that in losing touch with such places is in danger of forgetting its reason for being.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is the most famous progressive politician in the U.S. and the national face of young democratic socialism. On Election Night, though, Trump increased his share of voters in her congressional district by 50 percent compared to four years ago and shrunk his margin of defeat by 24 points — among the greatest fluctuations in the country. AOC’s district, the 14th, spans northwestern Queens, from gentrifying Astoria to multiethnic Jackson Heights to heavily Latino Corona. Moving north, beyond La Guardia airport and Rikers Island, it covers the Bronx’s Hunts Point Market, then moves into Parkchester, the Black, Latino, and increasingly South Asian neighborhood where Ocasio-Cortez was born, up through the eastern shore of the borough, past City Island and Orchard Beach, to the border of Westchester County, where she was raised.

Of all these areas, Corona fell hardest for Trump. If you slice a map of Corona into the jagged multi-block Tetris pieces known as election districts, you’ll see that every one of them went for Biden in 2020. Four years later, most went for Trump or narrowly for Harris, sometimes by a single vote. A heavily immigrant enclave of 110,000, the neighborhood is almost impossible to navigate without some Spanish and is effectively New York’s flyover country. Anyone who has taken the 7 train to see a Mets game or watch the U.S. Open has floated above its commercial thoroughfare of Roosevelt Avenue, which flows in from neighboring Elmhurst, another district that grew much redder in 2024. Corona was devastated by COVID. It is also one of the places that has borne the brunt of the migrant crisis, which has brought more than 200,000 new arrivals to the city since 2022, when Biden lifted Trump-era border restrictions and Texas governor Greg Abbott started busing asylum seekers north. While pockets of midtown Manhattan and the Upper West Side mounted resistance against new migrant-inhabited hotels, and violence and disarray around shelters in Randalls Island and Clinton Hill brought tensions of their own, it was along Roosevelt Avenue that the influx was most visible and controversial.

The essential issue there, as an aide to one local Democratic politician puts it, is that “the underground economy is completely overground.” Roosevelt Avenue and its surroundings have become saturated with two types of new arrivals: unlicensed street vendors selling food or merchandise and sex workers soliciting customers outside makeshift brothels. There is consensus among elected officials and residents that many of the women are sex-trafficking victims from Central and South America working to pay off their debt to smugglers. These factors have led to what residents describe as a quality-of-life disaster, coinciding with an uptick in crimes such as robbery and felony assault, which increased locally by about 50 percent in the past two years.

Beneath the tracks of the 7 train, it is not difficult to find newly galvanized Trump voters. Carlos Bermejo owns an Italian Latin restaurant called La Pequeña Taste of Italy. Bermejo, who emigrated from Ecuador, says the street vendors undercut his sales and the streetwalkers deter customers and attract crime. “In the summer, in the window, maybe like ten ladies,” he said. Inflation was another concern: Facing rising costs of his own, he says he had to hike the price of his standard aluminum-container takeout from $10 to $12. When I asked whom he voted for, he looked at me like I was kidding: “Donald Trump. You gotta do that. Everybody knows that.”

Several blocks away, the manager of a grocery store complained of a spike in thefts — he didn’t want me to use his name to avoid risking further incidents — as well as of street vendors pouring their grease directly into the sewer, which he said attracted rats that wound up in his store basement. He says he voted for Biden in 2020 and Trump this time around. Carmen Enriquez, a substitute teacher from Ecuador who lives nearby in what is technically Elmhurst, says she’s a registered Democrat who voted Republican this year for the first time. She complained that migrants had received free shelter and benefits while existing residents struggled. She directed her ire at not only the Biden administration but also Ocasio-Cortez, who appeared at a local rally last year to support migrant vendors, and State Senator Jessica Ramos, who co-sponsored a bill several years ago to decriminalize sex work. (It has not passed.) “You can see it all, the boobs out. That is outrageous. That is what I am telling you — especially the Venezuelans, they came with attitude.”

One of the most interesting people I spoke with was 57-year-old Mauricio Zamora, who lives just off vendor-packed Corona Plaza on 103rd Street. Zamora runs a Facebook page and an active WhatsApp group for an organization he founded called Neighbors of the American Triangle, named after a minuscule nearby park he started maintaining during the pandemic when it became a magnet for drinkers. I met with Zamora in his apartment, which his wife had already decorated with Christmas nutcrackers and tinsel. He arrived from Costa Rica on a tourist visa in 1995, overstayed it illegally while establishing a scrap-metal business, and gained citizenship in 2005. His English is still shaky, and an acquaintance helped translate. Zamora says he voted for Clinton in 2016 and Biden in 2020 but is now all in on Trump. TRUMP 2024 stickers are plastered on his apartment building, and the Facebook page is basically nonstop gloating about Trump’s victory.

His reasoning was heterodox. On the one hand, he had heard Biden would give amnesty to 15 million undocumented immigrants already in the country and was disappointed he didn’t. On the other hand, he supported Trump because he hoped to block further arrivals. Breaking into English, he pointed at me. “You open the door for the people to your house? Right? No, all right,” he said. “America is for working, yes? Not for robbing, right? Not for prostitution.” He says that thanks to the chaos on Roosevelt, he has been getting fined for random garbage in front of his home, which he owns. He feels some of his local representatives, meanwhile, have prioritized tolerance over law and order. Using our translator now, he claimed they showed up only for “LGBT mobilization or when the lady prostitutes do a rally.”

I didn’t speak only with Trump converts. The following day, I returned to the neighborhood to meet Massiel Lugo, a 32-year-old mother of two who works as a mental-health paraprofessional at nearby IS 61, one of the most consistently overcrowded public schools in the city. Her parents emigrated from the Dominican Republic; her father runs a bodega in Jackson Heights. We met at the Paris Baguette on Junction Boulevard, just north of Roosevelt. Lugo’s 15-year-old daughter, Jalene, carrying a Taco Bell bag and wearing a Slipknot T-shirt, joined us a little while later. Lugo’s 7-year-old son is autistic, and she says they no longer walk on vendor-filled Junction Boulevard because it causes him stress. Her larger concern is prostitution. “My daughter started complaining — you know, she takes the train to go to school, and it started bringing in more men.” And with them, perhaps, other problems like drug use. A quarter-mile west, I had walked by a few guys shooting up at “Fentanyl Point,” as one local described the corner. Lugo ultimately voted for Harris, at Jalene’s urging. “I know Trump wants to clean up the streets,” Jalene says, “but his idea of cleaning up is even getting rid of the people that were here legally.”

Everyone I talked to in Corona considered their presidential vote through the prism of local concerns, but it was not hard to see the national implications. The area’s pro-Trump turn mirrored Democratic losses on the U.S.-Mexico border and other predominantly Hispanic areas where the migrant crisis was acutely felt as well as in cities like San Francisco, where voters, fed up with its ongoing mental-illness and drug crisis, ousted the incumbent mayor in favor of a wealthy moderate with no public-sector experience. One theme connecting these geographically disparate regions was the inability of Democratic officials to fix or sometimes even acknowledge problems that were staring them in the face and that residents were imploring them to address. The party of government, predicated on using the state to help citizens in need of it, didn’t seem to be governing at all.

Corona’s city councilmember, Francisco Moya, a moderate Democrat and ally of Mayor Eric Adams, told me, “Trump’s message — which was like, ‘Are you better off today than you were four years ago?’ — has resonated: the economy, the quality of life, the migrant crisis here in New York.” A month ago, Adams and Moya launched “Operation Restore Roosevelt,” a 90-day crackdown involving multiple state and local agencies that has increased the police presence in the area.

The sweep was unpopular with progressives. State Senator Ramos, who has announced a bid for mayor, told me Adams’s move was mostly performative and wouldn’t root out the traffickers or gangs exploiting women. She added that prostitution has been thriving on Roosevelt for decades and was reluctant to point to the migrant crisis as a chief cause of Republican success in her district. But she acknowledged that this was probably not what voters wanted to hear. She herself lives across the street from a brothel. “My boys are in middle school; they take the train to school. They actually have to walk down Roosevelt Ave at 7 a.m. I don’t want them to be propositioned. I don’t want them to see adults in their worst possible behavior. That’s what is top of mind.”

The next morning, I continue north through the 14th District, taking the 6 train to the Parkchester stop in the Bronx. The borough, 85 percent Black and Latino, went 27 percent for Trump, nearly three times the rate it did eight years ago. South of the elevated tracks is Unionport, where in October Trump filmed a Fox & Friends segment at a barbershop called King of Knockouts. North of the tracks is the Parkchester complex, virtually a city unto itself, composed of 171 brick buildings that, like Stuy Town in Manhattan, were built in the 1940s by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. Just outside its walls is a Bangladeshi enclave of restaurants, groceries, and small businesses.

Farhana, who manages a store here — she didn’t want me to print which one or her last name — said she supported Jill Stein to protest Israel’s war in Gaza. One of her co-workers, a 19-year-old named Gabriel, voted for Trump. His parents came from Mexico as undocumented immigrants and feared ICE raids during Trump’s first term before becoming citizens. He says his mother voted for Trump largely on religious grounds, while he was focused on the immigration surge. “They’re over here bragging, like, about getting government assistance, when I saw my parents build everything from the ground.” He also expressed mild disappointment that Harris didn’t go on The Joe Rogan Experience so that he could “see what she is like as a person.” He asked me not to use his last name, lest anyone stigmatize his choice. “You know you’ve got to tell the girls, like, ‘Damn, I’m sorry Kamala lost.’”

While I was walking around, I took a call from Assemblywoman Karines Reyes, a Dominican-born oncology nurse who represents the area in Albany. It was striking how often the migrant crisis came up even away from its epicenter. Reyes says it was often her neediest constituents, of all races, who felt they were being forgotten. “I know so many people in our district who have vouchers that pay for housing,” she says. While they waited for city agencies to inspect and approve their lodging, among other bureaucratic hurdles, they felt migrants “were getting fast-tracked to shelters, they were getting cash, they were getting debit cards.”

Prior to the election, Reyes said, “we spent a lot of time talking about things like abortion in our community. Even though those are important issues, sometimes we feel like if we have those conversations about the immigration process being fair and equitable, that we are somehow sounding anti-immigrant. But people want us to address those things. They feel it is fundamentally unfair. For many of us, we didn’t want to talk about those things.” I asked if she meant herself, personally. “Absolutely. I didn’t want to talk about it.”

About a mile north on White Plains Road is Bronx’s Little Yemen, which straddles the northern edge of the district. The Yemeni Trump supporters I spoke with, some of them recent arrivals, cited entirely different factors. Jameel Ahmed runs a travel agency and shipping center and spoke only about the economy, citing pandemic assistance he credited to Trump. He runs the business with Hossam Al, who arrived in America just before Trump’s first-term “Muslim ban” and whose daughter was almost blocked from arrival. Al cited the economy, too, though he said he was also motivated by cultural factors. He says his kids’ local public school, ten blocks east, asked students from different grades to form a Pride flag by wearing different colored T-shirts, an activity he asked his children to be exempt from. He recently moved to Cypress Hills, Brooklyn, partly for its proximity to an Islamic school. “You don’t involve the schools in this matter, right?”

Across the street, outside the Bronx Muslim Center, Sammy Alkaifa, wearing a backward Jets hat, said he voted Trump because he thought he represented a better chance of ending Israel’s war in Gaza. Yahay Obeid, a former chair of the local community board and a regular media liaison for the community, represents an intriguing new type of unicorn constituent scattered throughout the district: the Trump-AOC supporter. He’s with Trump on tariffs, border control, crime, and “No shutdowns during COVID” but with AOC on Gaza. He sees no contradiction: “She is working hard for the working class.” Overall, the populist Ocasio-Cortez ran ahead of Harris in her district, and there’s probably a lesson there that transcends her own political talents or the uniquely cross-pressured voters in an area like this one. Ocasio-Cortez was herself intrigued by the split voters in her district, asking them to explain their horseshoe vote in a post to her 8 million followers on Instagram.

Even before the election, New York wasn’t as liberal as it seemed, as evidenced by the person currently running it. Some of the same factors that led the city to elect former police captain Eric Adams, who ran on a law-and-order platform in the midst of pandemic disorder, set in motion a shift that predated the migrant crisis.

Among the U.S. congressional district that swung as far right as Ocasio-Cortez’s was Democratic representative Grace Meng’s, which includes parts of the Roosevelt Avenue corridor as well as heavily Chinese Flushing and which Harris clung to by a 52-46 percent margin. Asian American New Yorkers had already begun drifting right by the 2022 midterms, galvanized by anti-Asian violence and concerns about the fate of a citywide standardized test — local issues that echoed national concerns that Democrats were soft on crime or discriminated against Asian college applicants via affirmative action. In 2023, the Bronx elected Kristy Marmorato, its first Republican on the City Council in 40 years. Her office is a short walk east from Little Yemen, past rows of single-family homes with American flags, in the traditionally Italian American neighborhood of Morris Park, whose Tetris blocks were already shaded purple in 2020 and this year swung eight points more toward Trump.

Denialism is not confined to the left, of course. Denialism on the right, which ranges from election denial to climate denial, is partly explained by the familiar problem of partisan echo chambers amplified by social media and Trump-onset hyperpolarization. But the conservative and liberal versions of the phenomenon have taken on different qualities, the former tending to indulge dark fantasies like QAnon and the latter more prosaically refusing to accept certain inconvenient realities, such as Joe Biden’s age-related decline.

And yet it is the Trump people who clearly had their fingers on the pulse of the electorate this year. And it is hard not to conclude that the main reason is the exact “diploma divide” that helped undo Harris’s candidacy, a divide that has insulated many journalists, scholars, and activists from the tribulations facing ordinary Americans. In some progressive quarters, the default reaction to problems that pointed to undesirable solutions often took the form of a kind of gaslighting. Why couldn’t voters see that inflation had in fact abated and that the country’s economic fundamentals were strong? Didn’t they know that while subway crime and gun violence technically had spiked, the city’s murder rate was in fact worse 30 years ago? In deep-blue areas, the migration surge was seen largely as a problem created by cynical red-state governors, rather than as a symptom of a dysfunctional asylum system, while one of the only ways well-off New Yorkers experienced the influx in their daily lives was when Adams temporarily cut public-library hours to address the cost of the crisis, which he put at several billion dollars per year.

In some quarters of the liberal coalition, there was surprising consensus about the meaning of the election, which resulted in the GOP’s first popular-vote victory in 20 years. “It should come as no great surprise that a Democratic Party which has abandoned working-class people would find that the working class has abandoned them,” said Bernie Sanders. The former congressman Conor Lamb, a onetime centrist darling with little in common with Sanders, delivered more or less the same diagnosis: “We’re never going to have a strong claim to government if we only speak for college-educated people in the big cities and suburbs.”

Yet as there was after Trump’s first victory, there have been attempts to wave away the result and its implications. Some have urged Democrats to create a “liberal Joe Rogan” to compete with the “bro podcasters” who have such influence with young men. This is a curious idea. For one thing, Rogan and his ilk are not traditionally conservative and in another era might well have been Democrats. (Indeed, before he endorsed Trump, Rogan had endorsed Sanders.) For another, it’s telling that some can’t envision an electorate-expanding influencer who isn’t already a liberal. As Democratic senator Chris Murphy urged on X after the election, “You need to let people into the tent who aren’t 100 percent on board with us on every social and cultural issue.”

Some have pointed out that Harris herself did not run a particularly left-wing campaign, though the results suggest she had trouble outpacing her recent past as a progressive and the party’s declining brand in general. Others have rushed to blame or pathologize Trump’s new voters. “It’s misogyny from Hispanic men. It’s misogyny from Black men — things we’ve all been talking about,” said MSNBC’s Joe Scarborough. And then there are the hard-core denialists who have landed on a diagnosis that doesn’t require the party or themselves to change course. Cox Richardson, whose 1.7 million subscribers may make her the most popular and well-compensated figure on Substack, framed the election result as a problem of gullibility: “In the U.S., pervasive right-wing media, from the Fox News Channel through right-wing podcasts and YouTube channels run by influencers, have permitted Trump and right-wing influencers to portray the booming economy as ‘failing’ and to run away from the hugely unpopular Project 2025,” she wrote. “They allowed MAGA Republicans to portray a dramatically falling crime rate as a crime wave and immigration as an invasion.” The New Republic’s Michael Tomasky concurred that the voters had been duped. “It wasn’t the economy. It wasn’t inflation, or anything else,” he wrote. “It was how people perceive those things.”

In Queens, at Paris Baguette, Jalene Lugo told me about an argument she had about the state of Roosevelt Avenue with a friend who lives in a three-story house in a nicer neighborhood. “He was like, ‘Oh, but you know, the person, they’re just trying to live their life.’ And I told him, ‘Well, you don’t know what it’s like here; your family’s higher class.’” Her mother, Massiel, says the people who clash with her about the situation are the ones she encounters on her Instagram feed. “All my friends and family members who are Democrats, they are exactly like me. The only people I know who are very liberal are in the comments.”